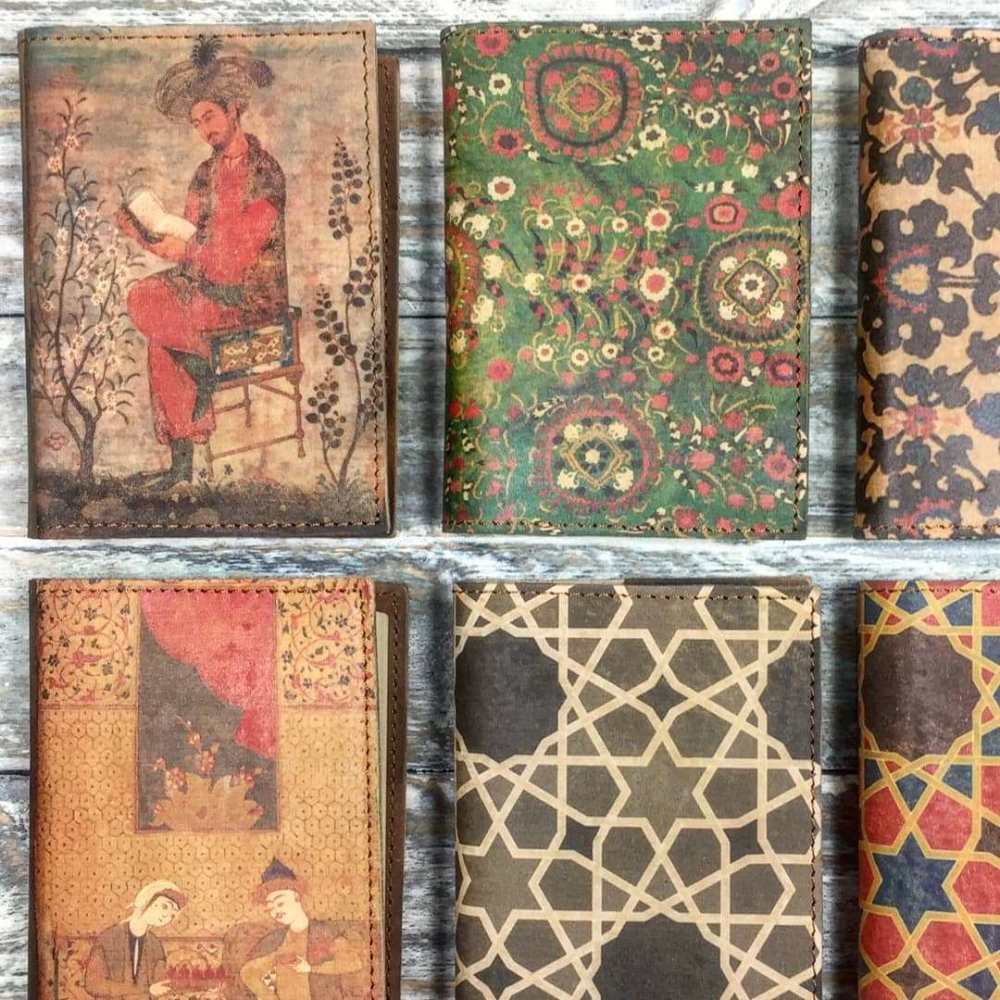

Uzbekistan’s beautiful architecture fascinates tourists from around the world, but they can not take Gur-Emir with them when they leave. Yet they can fill their suitcases with smaller items: painted pialas and teapots, colorful suzani and adras.

Snezhana Atanova

Snezhana Atanova is a PhD candidate at INALCO. Her thesis focuses on nationalism and cultural heritage in Central Asia. She recently finished an IFEAC fellowship devoted to national identity in everyday life in Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. She was awarded a Carnegie fellowship in 2017, in which she explored national identity through the nation-branding initiatives of Russia and Central Asian countries. She earned a Master’s in International Communication from the

University of Strasbourg in 2012 and a Master’s from the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO) in 2015.

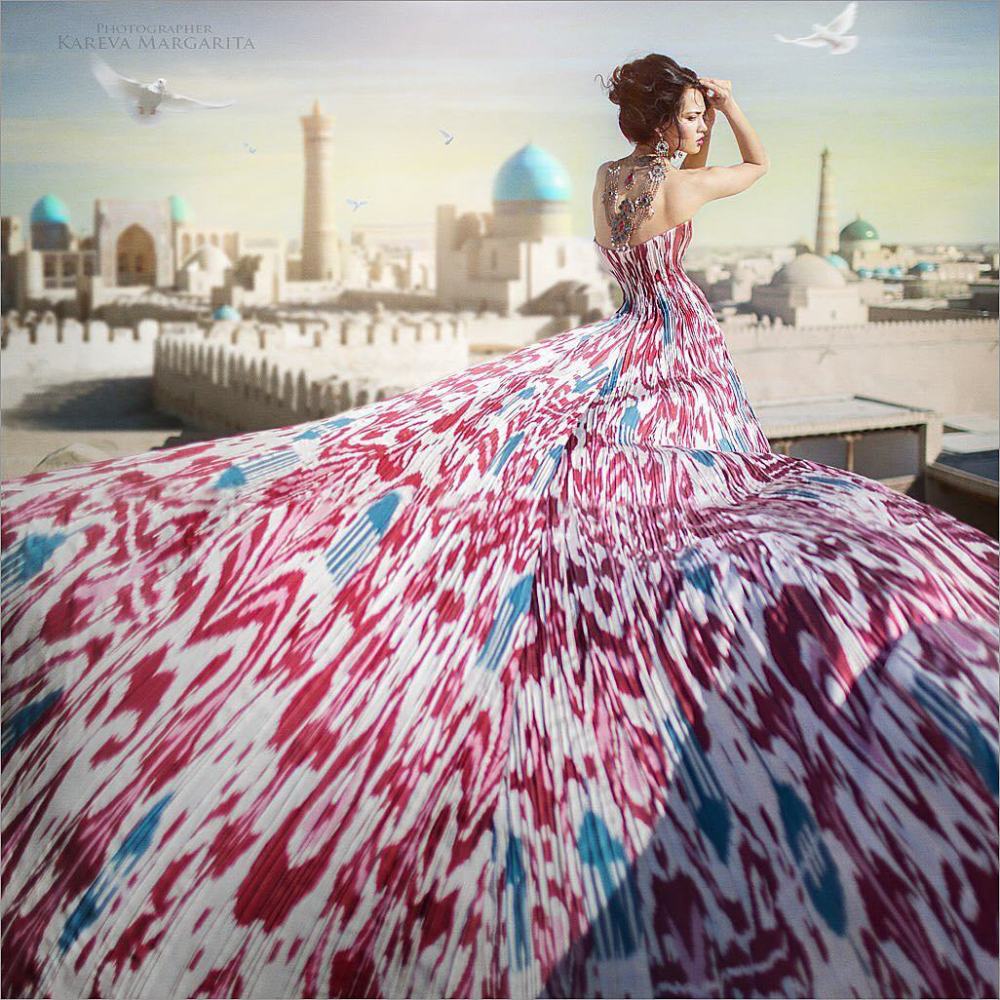

These bright ornaments are increasingly becoming global products: Oscar de la Renta was so inspired by ikat that he created an entire spring-summer collection of silk clothes with these motifs for the fashion house Pierre Balmain,[1] even traveling to Uzbekistan to commission fabrics for the line. The decision to have the fabrics produced locally is one that would likely have been endorsed by nineteenth-century French travelers to Central Asia, who openly acknowledged that the silks and velvets found at the Louvre, Printemps, or the Bon Marché in Paris could not hold a candle to those available in Samarkand and Bukhara.[2]

However, not all those who have incorporated ikat and suzani ornaments into their designs—ranging from haute couture designers like Balenciaga, Gucci, and Roberto Cavalli to mass-market brands like Zara, H&M, and Forever 21, and even interior collections by Susan Deliss and Madeline Weinrib—have mentioned the origins of these ornaments.

Even as the world of Western fashion appropriates Central Asian culture, promoting globally recognized brands without acknowledging the national ornaments that inspired and adorn these items, Uzbek designers are creating their own collections.

This effort may one day restore the balance by telling the world about the cultural traditions of Uzbekistan and the region as a whole.

Authenticity and national specifics, modernity and tradition are the most frequent epithets attached to the question of “Uzbek fashion.” Before ever visiting Uzbekistan, I heard from friends in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan about trendy looks being produced by the country’s local couturiers. I flew to Tashkent to discover this fashionable world and to find out what fashion trends are being created by local designers.

The richly ornamented clothing and accessories at Tashkent’s Chorsu bazaar or Samarkand’s Siyob bazaar do not claim to be exclusive in terms of their cut, which is simple, but are unique in terms of their ornamentation, use of color, place of production, and nature of production. In the collections of local designers, the above components are combined with creativity and quality execution. Whether purchased at the bazaar or from a local designer, a chopan cannot be compared with a dress from H&M: even if the latter is more expensive, the items available in Uzbekistan are not mass-market products.

In this review of Uzbek fashion trends, I aim to present designers whose collections are modern and yet traditional. Their works are full of meaning: they are produced in Uzbekistan by Uzbek masters and from local materials; they stimulate the development and preservation of the country’s textile and craft traditions; and they promote cultural heritage and help with national branding. Entrepreneurship in the fashion industry speaks to the free development of this industry, while fashion itself conveys important messages about members of the national community.

Fatima

The Fatima boutique is located in a shopping mall on the pedestrian street on Tashkent Street, just between Registan Square and Bibi-hanym mausoleum. With its colorful displays of chopans, dresses with ikat ornaments, embroidered suzani, and ladies’ bags, the boutique looks like something out of an Oriental fairytale. Although some of the mannequins wear modern dresses with delicate inlays of ikat prints, the majority of the collection is comprised of silk chapans and other elements of traditional costumes, complete with fine embroidery.

Fatima Gulyamova, who originated and owns the brand, has been creating her own collections since the 1990s. She can spend hours explaining how she restored a colorful decorative band (braid) from old photographs, how she created ikat patchwork for bags, and how long it took her to choose adras from Margilan masters. In the production workshop adjacent to the showroom, several dozen seamstresses can be found hard at work, their heads bent over hand embroidery. This not only emphasizes the exclusivity of the products available in the boutique, but also creates jobs and supports traditional handicrafts.

During my visit, tourists from Kazakhstan, looking for something authentic, came in and bought chapans. Tourists from Germany purchased suzani, while a tourist from Russia went away with an embroidered bag. These items are also in demand in the Siyob bazaar, a five-minute walk from the boutique, but while the prices of these colorful, authentic goods are lower at the bazaar, sophisticated tourists prefer to shop at Fatima’s boutique owing to the higher quality of execution and greater creativity of products.

Kanishka

I first heard about the Kanishka brand from a friend in Ashgabat, then from friends in Bishkek and Moscow. The fact that it was so well-known internationally prompted me to go to “Kanishka” on the very first day after I arrived in Tashkent. It quickly became apparent that it had high name recognition in Uzbekistan, too: passers-by were able to point me in the right direction when I got lost looking for it.

The Kanishka collection does not include traditional clothes, only T-shirts, sweatshirts, jackets, coats, backpacks, and other items integral to the daily life of a modern urbanite. Ikat and suzani are present in cloud-colored prints on knitwear and patterned embossings on leather. Prints range from oriental miniatures to Mickey Mouse to an Uzbek girl against the background of a satellite.

Alexei Manshayev, the talented antiglam creator of the brand, is able to do everything at his production facility, which houses several specialized workshops and employs a large team. Photos for the brand’s pages on social networks are taken at the production site itself. Currently, over 50,000 people from Uzbekistan and beyond follow Kanishka_dsgn on Instagram and Facebook.

Both Kanishka and Fatima seem to have found their niches in Uzbekistan and the region, and do not appear to want to conquer high podiums or win international audiences.

Bibi Hanum

The Bibi Hanum brand, meanwhile, is more interested in gaining international recognition. The brand’s products are exhibited in the souvenir shop of the George Washington University Textile Museum; Bibi Hanum also presents its collections at international exhibitions and festivals, among them the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, Coterie in New York, and the International Business Festival in Liverpool. The main mission of the brand is to create economic opportunities for Uzbek women from Tashkent, the Ferghana Valley, and Navoi region, and to preserve the cultural heritage of the country. The founder of the brand, Muhayo Aliyeva, started by opening the family studio, where she worked alongside her sister. Bibi Hanum appeared later, after Aliyeva won a Dutch grant to restore and popularize the national chapan. Understandably, therefore, much of the Bibi Hanum collection is comprised of variations on the theme of chapan. Overall, the brand’s offerings can be summarized as clothes, accessories, and home furnishings with suzani embroidery and ikat-inspired motifs with hazy effects, as well as wooden women’s jewelry painted with ikat ornaments.

Unlike the brands discussed above, prices at Bibi Hanum are prohibitive for the majority of the Uzbek population. To take one example, a small silk wallet from Bibi Hanum would cost at least $62, more than double the $20-$25 cost of a leather wallet with an ikat– or suzani-themed print from Kanishka. Thus, Bibi Hanum’s efforts to popularize ikat and suzani are oriented toward a wealthy international audience that is willing to shell out significant cash.

As an Uzbek representative of haute couture, Bibi Hanum seems to demonstrate the potential of Uzbek fashion. The international popularity of an Uzbek designer collection increases the chances that adras with ikat-inspired motifs and colorful suzani will become fixtures of the global high fashion scene.

Fashion has always been—and continues to be—a means of influencing society. By showing off wealth and high status, clothing style can reinforce antagonism in society or, on the contrary, strengthen ties between members of that society.[3]

The democratic potential of the modern Uzbek fashion industry is reflected in loyalty to traditions, support for national fabrics, relations with the local community and small producers (especially women), the potential for engaging independent artists, and the development of organic fashion entrepreneurship and job creation in the country.

Fashion is often associated with elitism, but ikat and suzani entered the world of haute couture from the hands of Uzbek masters. Same masters also supply their creations to Central Asian bazaars and local designers’ workshops. Ikat and suzani ornaments will always be part of the history and culture of Central Asia, as well as central elements of the dress code. They will always tell us “Made in Central Asia.”

The world of Uzbek fashion is diverse. The simplicity of the cut is compensated for by the complexity and richness of the ornamentation, traditionalism competes with modernity, and ikat “affordable to all” coexists with that “for elites only.” For a more complete picture, let me present a few more gurus of Uzbek fashion whose works are already known inside and outside the republic. These designers are united by the desire to preserve folk art and tell international audiences the story of Central Asian suzani and ikat. At the same time, their collections and creator-client interactions convey a wealth of messages that can be interpreted through different frames: fashion and sustainable development, fashion and feminism, fashion and transnationalism, fashion and orientalism, fashion and post-colonialism, fashion and democracy.

Dildora Kasimova—Dildora Kasimova

A regular participant in Uzbekistan Fashion Week, she was The MAG magazine’s designer of the year in 2016. Kasimova artfully combines the East and the West: the beaded and silky patterns of her Victorian capes are reminiscent of ikat-inspired ornaments, she uses suzani for wrap skirts, and her classic suits and jackets with cut sleeves made of silk adras call to mind Oriental miniatures.

Dilnoza Umirzakova—Anor Atelier brand

A graduate of the Institute of Foreign Languages, she is now a participant in global fashion shows. In her collection, Umirzakova focuses on the ancient Uzbek cut “Nursak.” The brand’s elegant manto are reminiscent of the Kaltacha dress, which was widespread in the Bukharan oasis in the nineteenth century. Bold mini-dresses are presented alongside floor-length dresses.

Alexandra Chichinova—Sa-Sha brand

A winner of prizes at international competitions and a candidate for UNESCO’s quality mark, Chichinova creates knitted sweaters with ikat-inspired ornaments, elegant handbags made of silk adras, and mini-dresses made of striped bekasam, as well as pairing chapan with jeans. She is not afraid to experiment with ikat ornaments, using an ombre effect. Her collection includes outfits that refer to the past, including paranja dresses that have false sleeves and fasten with ribbons in the back.

Saida Amir—Saida Amir brand

A graduate of the K. Begzad National Institute of Arts and Design and St. Martin’s College in the UK, Amir is inspired by suzani embroidery. She gives these ornaments, which protect against the evil eye, a futuristic twist. Among the items in her collections are classic jackets with Uzbek stitching. She has developed the collections “Cezanne’s Legacy as an Inspiration,” “New Sarts,” “Passion for the East,” and “Nowruz,” among others.

Zulfiya Sulton—Zulfiya Sulton brand

A graduate of the National Institute of Arts and Design, Sulton is one of the leading designers of Uzbekistan and dresses a number of Uzbek celebrities. Her collection is dominated by evening toilettes: weightless gauze and Margilan excelsior silk are combined with bright shoya and adras. A participant in numerous fashion shows, Sulton continues to experiment: she has embroidered adras with silk patterns, added a flounce to the hem of chapans, created elegant velvet coats embroidered with suzani, and made luxurious evening dresses with long trains from adras.

[1] Smithsonian’s Freer/Sackler weaves together traditional and contemporary fashion. http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2018/03/25/36261454.html (24.11.2018)

[2] Napoleon Ney. En Asie Centrale à la vapeur. Paris. 1888. P.426

[3] Miller, Joshua. 2005 .Fashion and Democratic Relationships. Northeastern Political Science Association 0032-3497/05 $30.00 www.palgrave-journals.com/polity