The novel O’tgan Kunlar (“Bygone Days”), by the Uzbek writer Abdulla Qodiriy, is a true cult work of early Uzbek realism. Qodiriy had a tragic fate: he was purged and shot at the age of 44. Just ten years after his death, his novel was translated into Russian, though significant portions of the text were cut.

Today, American specialist Mark Reese heads up a project that aims to translate the novel into English. Reese, the Director of the Center for Regional Studies at the US Naval Academy, has been studying Central Asia for 23 years—including eight years of fieldwork, for program management as well as academic research. His website, The Uzbek Modernist, is dedicated to the novel O’tgan Kunlar and its author, Qodiriy, but also contains a bibliography of works on the history of the region.

About

Mark Reese

Mark Reese began his twenty three year career in Central Asia as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in the second group to serve in Uzbekistan from 1994-1996. He has engaged in eight years of Central Asian based regional field work in a full spectrum of activities ranging from program management as country director for the Department of State’s Uzbekistan Partnership Program in Comparative Religious Studies, interpreter and consultant for the Department of Defense, as well as in-country academic research and scholarly translation. Mark has worked as a site manager for the United States Special Operations Command managing translation and cultural advisement contracts. Upon leaving USSOCOM he held positions as Deputy Director for the Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies and Director for the Center for Regional Studies at the United States Naval Academy.

The first question is obviously “Why Qodiriy?” What attracted you to this writer, who is not very well known outside Uzbekistan and who had a tragic fate? Why do you think the Western readership will be interested?

I served in the Peace Corps between 1994 and 1996 as one of the first volunteers in Kokand, in the Ferghana Valley. Before I left home, I had absolutely, positively no knowledge of Soviet Central Asia, and by the time I finished my service, I had more questions than answers. Back then, there were very few reliable dictionaries or language materials, and the maps of the Soviet Union only showed Tashkent as a star on the lower right corner of the Uzbek SSR, just north of Afghanistan.

A young man from Arizona, I was a bit of a kolkhoznik. But Kokand in the 1990s was a wonderful place to serve and I gained invaluable insight into a conservative community. All the stereotypes we held in the West about the Soviet Union, Muslim culture and Islam, and the newly independent states were completely false. In many ways, I believe people in Uzbekistan taught me more than I ever taught them.

After my service, I went on to graduate school at the University of Washington, which gave me a solid academic foundation for what I had learned in Peace Corps. During graduate school, 9/11 occurred.

I returned to Tashkent, Uzbekistan in 2002 in order to study for my exams and manage a comparative religious studies grant. To prepare for my exams, I was tasked with translating the first three chapters of Abdulla Qodiriy’s O’tgan Kunlar (Bygone Days). Once I began, I became completely obsessed with finding out how the novel ended, and so I read the whole thing.

I quickly learned during my time in Tashkent that everybody in Uzbekistan has an opinion about O’tgan Kunlar. It became clear that Qodiriy was a beloved literary figure and that I was gaining insight into an aspect of Uzbek culture that very few people ever learn about.

I consider my background as a working-class guy from Arizona to be a baseline of American culture.

I will not go so far as to paint my fellow countrymen entirely as provincials, but we can be egocentric, and isolationist traditions run deep. 9/11 brought a part of the world into our lives that we have now been struggling to understand for fifteen years. That engagement has prompted an upsurge in interest in international travel, food, and historical epochs previously unknown to us. I hope that by exposing O’tgan Kunlar to a broader readership, Americans will come to understand that Central Asia is a unique place and that the typical stereotypes do not come close to capturing the region’s qualities.

How dramatic is the figure of Qodiriy? How close he is to the Jadids, and in what ways? Do you think these Jadidi thoughts (and the book itself) can resonate with modern-day youth and a modern readership?

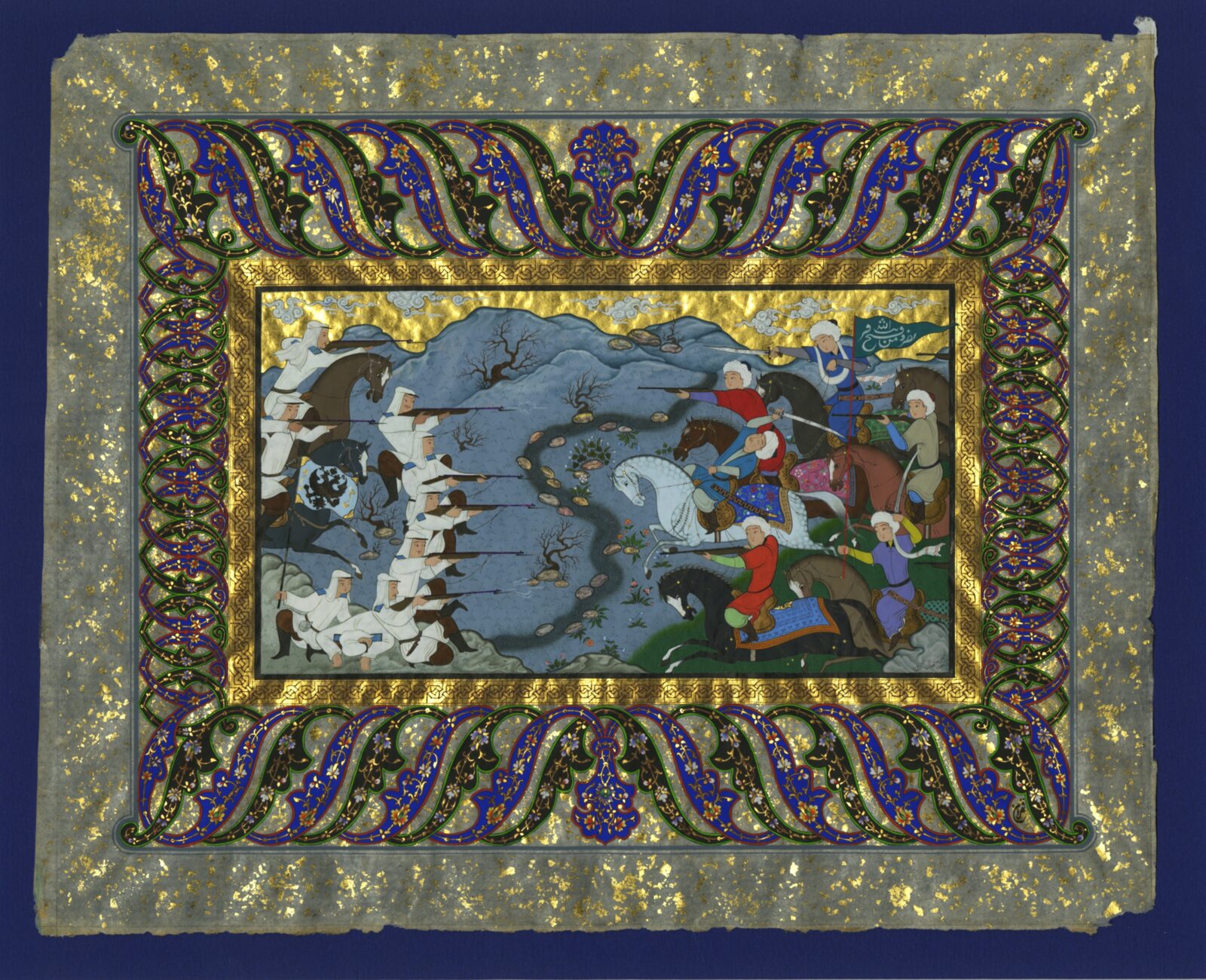

The aspect of this project that has affected me the most has not been the actual translation so much as Qodiriy’s character as a man. He speaks directly to the reader throughout the novel, so you get a sense of who he was and what his concerns were when writing a novel. He could be anyone I knew/know in Uzbekistan: people who taught me how to treat a guest, how to be honest and speak your mind, how to comport yourself as a young man. In Hyit in 1995, I prayed Namos with thousands of men at Juma Madrassah in Kokand. I understood then that there is really only one race—the human race—and every other distinction is trivial. In his chapter “Massacre of the Qipchaks,” which appears in Volume Three, Qodiriy makes the same argument. In the chapter “Yusufbek Hajji Disavows the Ways of the World,” he furthers that argument: why condemn a whole people because of their race, all to advance the career of one man? When an author who was purged in 1938 can speak to a guy from Arizona on an emotional level that I can empathize with, that author has achieved a hallmark of all great literature—universality. He was a dramatic figure because, inevitably, he died for his beliefs, along with millions of other people. Various sources make it clear that he knew the risk he was taking. I respect anyone who is willing to make that sacrifice for literature and art.

I believe the Jadid movement is a term we use to help describe our own understanding of what Adeeb Khalid called “a cultural efflorescence in a time of conflict and change.” There is great evidence to show that change was already happening within the Kokand Khanate before the arrival of the Jadids. Devin DeWeese and Baktiyar Babajanov have done much to show that Central Asia did not live two hundred years in darkness to only be saved by the Jadids. My next post will deal with the relationship between nomadic and sedentary groups within the Kokand Khanate, but it is fascinating that the initial leaders of the Kokand Autonomous Republic were Kazakh. Did this ethnic heterogeneity in Kokand’s last gasp of a modern Muslim republic occur only because of the Jadids? Not likely, but we can say that they gave voice to the zeitgeist through modern means of communication. They articulated values that still resonate throughout Central Asia today. And their ability to articulate modernity and reform made them easy targets for a purge.

So we use the term Jadid to describe a broad social phenomenon that first became apparent in Central Asia in approximately the mid-nineteenth century and continues to this day. But we should also understand that the Jadid movement worked in tandem with other post-colonial movements throughout the world. We can easily categorize Qodiriy as a Jadid reformer in order to articulate for ourselves where he stood among the hundreds of social “categories” that were vying for survival at the time. We use the term to describe a moment in history.

Cholpan and Fitrat also come to mind as part of the Jadid movement, though the three followed their own ideological tangents. To once again cite Khalid, Fitrat was “a giant among reformers” whose work was edgier, even avant garde. Cholpan translated Othello into Uzbek! But Qodiriy, in my opinion, is so beloved and well remembered because he captured the ideas of memory and loss felt by a society changed irrevocably by conquest and Soviet homogenization. All three enjoyed Russian language and culture, but inevitably came to refute the direction of the post-revolutionary enterprise. I am not the sort to decry “the evils of the Soviet Union,” but cataclysmic change took place in Central Asian society during the Tsarist and Soviet periods—and Qodiriy tapped into those feelings in O’tgan Kunlar.

What explains the success of O’tgan Kunlar among the intelligentsia? How did Qodiriy influence the Uzbek literary school?

Great question. I think O’tgan Kunlar is well known primarily among the intelligentsia. Everyone knows the novel—just as, maybe, most American children know Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. It is taught in schools throughout Uzbekistan, but it really takes a specialist to capture the aspects of the novel that go deeper than the romantic love between Otabek and Kumush.

Many descendants of the Jadids are still alive today. Khonadmir Qodiriy still lives in his grandfather Abdulla’s home. Among the descendants of reformers— historians, actors and actresses who knew Cholpan and acted out Othello for audiences in Tashkent in the 1920s—can be counted patrons of the arts in Uzbekistan. In Kokand, the son and grandson of Abidjanov, who established the first printing press in that city and agitated for the Kokand Autonomous Republic, are both alive and well.

In many senses, the intellectual elite of all former Soviet republics—both descendants of the Jadids and otherwise—found themselves engaged in an extremely dangerous balancing act.

The tragedies of Soviet history were still very much a part of collective memory. Bad things could happen to good people. Most of the young people in the states of the former Soviet Union only know these moments of pain through history books, but their ancestors paid a very real price to maintain a system as interlocutors and intermediaries in a game that was often zero-sum. In many respects, the Jadids are symbolic of the first generation of Central Asians to articulate that pain. I therefore view the Jadids as one of the many groups of intellectuals that paid the ultimate price for the free expression of ideas. In Qodiriy’s case, he set the benchmark for Uzbek literature and standardized Uzbek prose for the generations to follow.

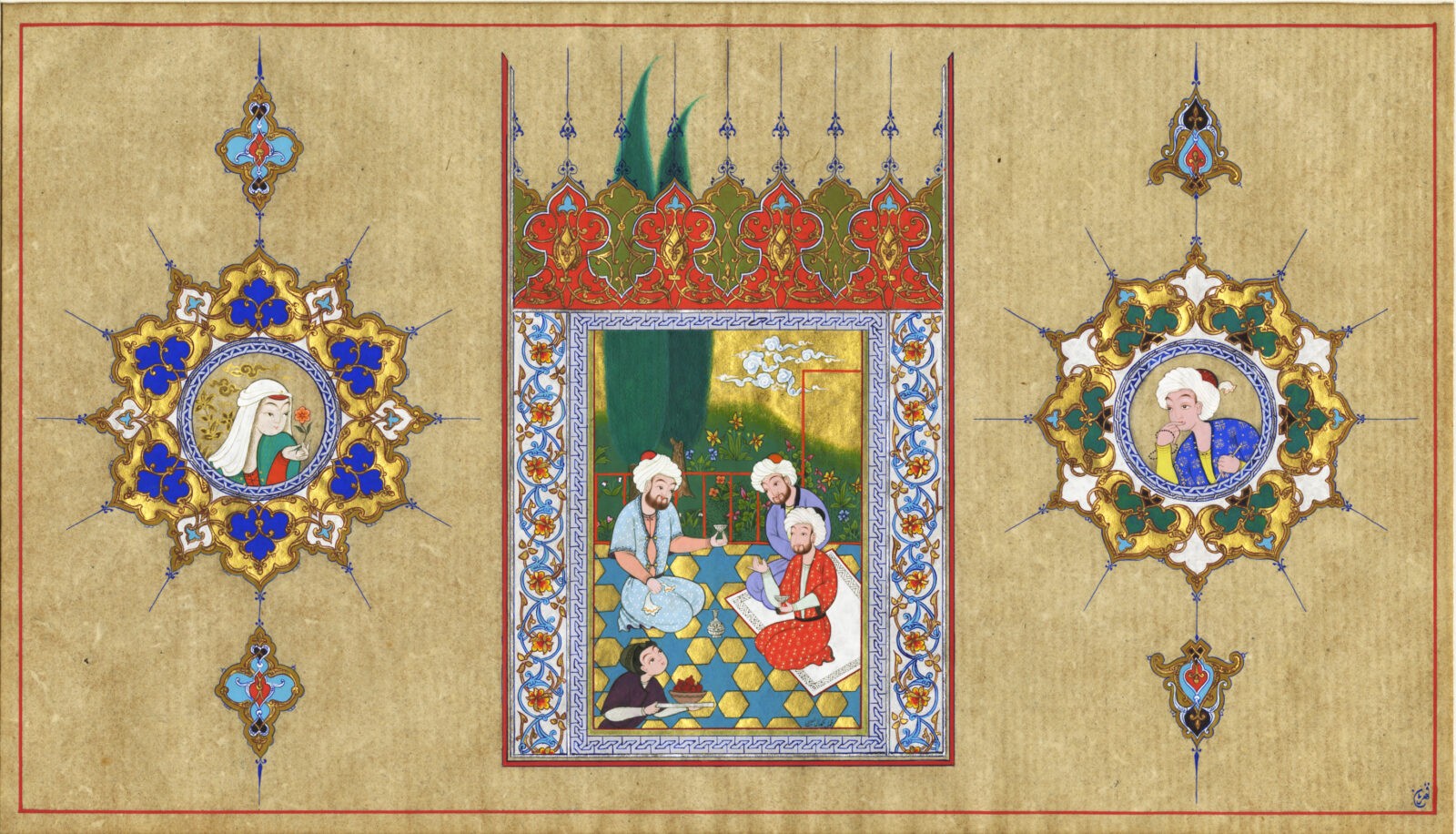

Miniatures by Kamollidin Mirzaev and Qahramon Shoislomov. Copyright protected, not for reproduction or distribution

What difficulties (if any) did you face in translating O’tgan Kunlar? Did you receive any support? How do you like the film versions of the book produced during the Soviet era and during independence?

I honestly think that I must be mentally ill to have pursued this project for so long…The language is dense and archaic, for one. Qodiriy himself admits that he is experimenting with a new medium; in the prologue and a note just before Volume Two titled “Apologies,” he even apologizes for his mistakes and the delay in producing Volumes Two and Three. So on a technical level, the opaque language used is a real pain to put into the proper context and intent of the author.

The translator Edith Grossman, who rendered the definitive translations of Don Quixote and Gabriel García Márquez’s novels into English, really helped me out in terms of translation theory: Read the book, get a sense of the story, but more importantly know when to “break the rules.” A translator has to sort of retell the story in the spirit of the author. If you don’t know the author’s culture or mindset, you are lost. I’ve seen attempts by Westerners to translate snippets of the novel, and they all try to create a majestic Shakespearean language. That’s a mistake, really. Qodiriy was first and foremost a humorist: he tried to capture both common language on the street and the irony of court life. He was a modernist and a realist—if I can use those terms—and he wanted to create something that encapsulated the loss of all aspects of Central Asian culture. So a translator has to capture that spirit but know when to break the rules and when to follow them!

In terms of help: dozens and dozens of people have helped me over the past 15 years—some wittingly and some unwittingly—and some represent a cautionary tale. I am grateful to all of those who rendered aid. The book will have a huge acknowledgements page, but for now, the two editors— Umida Khikmatellaeva and Umida Hashimova—are first and foremost in my mind for immediate thanks. They held different roles as editors. Umida Khikmatellaeva worked with me from the very beginning, even giving me grammar lessons in Tashkent in 2002; she has been the Oi Mullah of the project, offering advice and corrections. She is an institution and has helped legions of students over the years. Umida Hashimova has a genuinely scary level of persistence and talent. She would be the female Yigit of the project.

You must always, always, always take an “inside out” view of translation or any research. You must always remain humble about and suspicious of your work.

Instead of viewing Qodiriy and O’tgan Kunlar the way I want to see them, I need to place greater weight on how Uzbeks see them. That is the great challenge.

Is your project “The Uzbek Modernist” about Qodiriy, or does it have larger aims? What are your thoughts on how modern states preserve, alter, or censor Central Asian culture?

With “The Uzbek Modernist,” I am really engaged in an act of catharsis. I have 23 years of experience in Central Asia and I want to get it all out there in a format that is easy for people to access. I would love to write a screenplay for O’tgan Kunlar and translate Mehrabdan Chayon into English, but as part of a larger group that involves all generations of Western and Uzbek translators. I would like the site to become a platform for those interested in writing articles about Qodiriy and other Central Asian authors. Literature is sorely neglected in Central Asian studies and I want to contribute. So I am happy to accommodate scholarly submissions!

On the question of the modern states, in many ways the saying “All translation is betrayal” is instructive. I see the veneration of Timur and other “greats” of Central Asia as a natural process of reconstructing a national narrative, and many of these figures are worthy of our attention and study. Keep in mind that engagement with Timur, the Chagatay Gurungi and O’tgan Kunlar, among many other Central Asian institutions, was illegal (or seriously discouraged) for a large part of the Soviet period. These experiences are deep-seated in the generation that lived it and should not be dismissed outright.

After independence, some elites put certain heroes on pedestals for altruistic reasons, others not so much. Just as with the Jadids, there is a whole spectrum of motivations and reasons behind what they advocated for.

At times, I think we put so much thought into this issue that we neglect the time-worn maxim that stuff happens for no reason at all—don’t expect a grand plan…

Censorship does bother me, however. If I can’t appeal to the better selves of those who censure to stop them from doing it, I think they should understand that, from a purely pragmatic standpoint, censorship doesn’t work for too long and it rarely achieves its goal. If giving people the right to shape their own narrative under your leadership will hurt your feelings, I sort of want to ask: are your beliefs so thin that you can’t or won’t take a beating over them? Qodiriy did.

People will find a way to effect change. My grandfathers loved Nathan Bedford Forest and Robert E. Lee; I personally think it is time to take down monuments that venerate leaders who broke their oath to defend the Constitution of the United States of America, a document I fervently believe in. I believe that for the vast majority of Americans, the social contract has changed: Confederate generals no longer represent who we are. We want new faces and voices that truly reflect the nature and soul of our community. Thus, while the question asks about Central Asian elites, I would say that the US is currently going through the same process. That would be an excellent comparative study and everyone would benefit from such a debate.

From the Chapter:

A Young Man Suitable for the Khan’s Daughter

Commentary: We know that Qodiri was purged in 1938. What he captures in this chapter is his overall admiration of Russian development, especially political reform, and his desire to see those changes occur in Central Asia. Yet, throughout the novel he becomes highly critical of Russian military advances in Central Asia and especially the sullying of Turkistan’s purity through their influence. So we see a complex relationship brought out in the novel between Reform minded Jadids and Russian expansion in Central Asia. Also, Qodiriy begins to show the subtle symbiotic relationship that settled and nomadic peoples held especially in regards to trading.

Few in Turkestan had ever traded in Russian cities. Otabek, who had actually been to a foreign country, had a unique perspective among the people at the meeting.

Qutidor and Ziyo Shohichi, who heard all sorts of fantastic tales about Russians, were very interested to hear more about the truth of those rumors from Otabek and asked him to give his impressions of Shamai. Otabek relayed his memories of the city. His audience sat fascinated by Otabek’s clear articulation of Russia’s political, economic, and social development.

“Before going to Shamai, I thought that all government systems were like ours,” stated Otabek, “but my travels there changed this opinion. My experiences deeply affected my beliefs about life, transforming me. When I saw the Russian government’s policies, I realized that our leadership’s approach and tenets are frivolous, as if we are playing at governance. I cannot imagine what will happen to our situation if our government continues with this current anarchy… When in Shamai, I thought that if I had wings, I would fly to my motherland, I would descend directly upon the Khan’s palace and implement each and every one of Russia’s governmental policies. The Khan would take heed of my proclamations, writing decrees benefitting all levels of society, ruling by enlightened Russian ideas. In one month I would see my people on the same level as the Russians. But, when I returned to my homeland from Shamai, my dreams and aspirations showed themselves to be mere fantasy. No one would listen to me. Even when there were people who were willing to listen, they would retort, ‘Will the Khans listen to your dreams and will the Beks even carry them out?’ With this simple question they shattered my dreams. At first I could not fathom that they actually believed their own words, but later I found that they spoke the truth. Indeed, who will listen to the prayers of the dead baring their soul to the living? Will those already buried in a cemetery listen to calls for help? Who will listen?”

The group was held in rapture to Otabek’s impressions, listening in disbelief to ideas and views they had never before encountered. These “Fathers of Turkistan” who had never even considered such a course for their motherland fervently latched onto Otabek’s vision of a future which rose deep from within his pure heart and clearly expressed with the most sublime intentions.

“If we had a Khan like Umar Khan ,” said Qutidor “we would overtake those Russians.”

Ziyo Shohichi disagreed: “We found ourselves in this situation because of our own behavior.”