Author

Elmira Gyul

Professor, Chief Researcher at the Institute of Art Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Lecturer in the Republican Scientific Consulting Center NC Uzbektourism.

Furious and breastless

A legend about forty warrior women called Kyrk Kyz—fierce and strong Amazons capable of fighting alongside and against men—is a legacy of the nomadic steppe culture.

According to anthropologist Balkis Karmysheva, this legend was not made up by foreigners but took roots inside Transoxiana itself. In ancient times, when men went off to battles, the elderly, along with the women and children, stayed in the mobile settlements of steppe-dwellers, and it was them who had to undertake the function of protecting the tribe. Therefore, in nomadic societies, girls were taught at a young age how to handle arms just as well as the men.

When the ancient Greeks encountered the nomads of Asia for the first time, they wrote about the mysterious Amazons and how they cut off their left breasts in early childhood, as it was more convenient to shoot a bow without one breast.

Of course, female Scythians and Tomyris, their celebrated queen (who once led her armies to defend against an attack by Cyrus the Great, and, according to Herodotus, defeated and killed him in 530 BC), did not do anything with their breasts. These stories only reflected the immense surprise of the Greeks who caught sight of these women-warriors and believed they were furious men-haters. In addition to such unusual women, the ancient Greeks also wrote of encountering men who seemed to be half-men, half-horse.

It is most likely that these dwellers of “elegant” Greek poleis had a sort of cultural shock because of the nomadic “barbarians” who moved around, ate, and even slept in the saddle…

This is how the mythology of half men-half horses and breastless women was born in the ancient world.

Legends around the name

One of today’s tourist attractions in Uzbekistan is a crumbling fortress dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries called Kyrk-Kyz (“Forty Girls”). The fortress is located in Surkhandarya, about three kilometers to the east of the city of Termez.

Termez is a city in the southernmost part of Uzbekistan near the Hairatan border crossing of Afghanistan. It is the hottest point of Uzbekistan. In ancient times there was an important crossing on the Amu Darya river. From the 9th to the 12th centuries Termez was a big city and a cultural centre and was popular for shopping and crafts. In 1220 after a two-day siege, the city was destroyed by the troops of Genghis Khan.

According to the legends popular among the local people, 40 girls who lived behind the fortified walls of this fortress fought back the attacks of the foreign nomads. They were led supposedly by a local queen called either Gulsim (or Gulaim, or Gauhar). When all the men staying in the fortress were killed, 40 young girls stuck by her and together they successfully countered the enemy’s attack.

But Kyrk-Kyz has been a common name for the area for too long to take this story for granted. It is more likely that the forty Amazons represent the collective image of nomads and steppe women, and it is unlikely that they would have lived in this monumental, formerly grand building.

The Islamic tradition also had an interpretation of who the Kyrk Kyz were. They were perceived as righteous women who either defended the castle or were concubines whom, upon their request, Allah turned into stone to save them from their persecutors, or “infidels.”

In any case, the real story remains unknown, but there are different versions of it by modern scholars. Some think that the castle was used either as a caravanserai (a roadside inn for travelers), or as a country castle-palace—the summer residence of the rulers of Termez. The area where the castle is currently located was called Shahri-Saman in the last century. Because of this, some researchers have associated the building with the Samanid dynasty. The dating of the castle’s construction also favors the version with the Samanids as most references state that the castle was built in the 9th-11th centuries, i.e. during the ruling of the same dynasty from 819 to 999.

However, an additional version—likely more accurate—asserts that “Kyrk Kyz” was a spiritual sanctuary, known as a khanqah, and was built in the end of the 14th–15th centuries for dervishes and members of the Sufi faith. This theory is what Elizaveta Nekrasova, an Uzbek archaeologist, proposed after she carried out archeological research there in 1980s and did not find any evidence to support the earlier dating. Nekrasova believes that the inhabitants of ancient Termez, who had barely survived the massacre committed by the troops of Genghis Khan, were eager to fully rebuild their city. As they lacked time and resources, they used the most affordable and cheap materials in their construction. This is how Shahri-Saman was built: a mud city from hand-formed bricks made of clay and hay. There were plenty of these raw materials on the banks of the Amu Darya. At that time, Kyrk-Kyz was a part of the new city and not on its outskirts as it is today.

Beginning in the last third of the 14th century, the territory of Surkhandarya was under the reign of Timur. The Termez rulers were on a friendly footing with their ferocious northern neighbor—the conqueror of the half-world—and Timur himself treated them with great respect, as they were the Seyids (descendants of the Prophet) through Fatima, his daughter, and Hussein, his grandson. Even today Termez has preserved a majestic Sultan Saodat complex known as “the rule of the Seyids,” a group of mausoleums where many famous members of the ruling family were buried.

The castle of Kyrk-Kyz

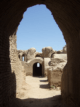

I happened to be there about six years ago. Its crumbled ruins and accurate brickwork still fascinate every visitor. A walk through the arches and a view of the elegant lines immerse you into the depth of centuries and dreams of the history.

Kyrk-Kyz. Photo taken by the author

Notwithstanding their seemed inaccessibility, these towers had no defensive function

Kyrk-Kyz is a square building (54×54 meters) looking at all four directions with massive towers flanked at the corners. Notwithstanding their seemed inaccessibility, these towers had no defensive function: they are hollow, isolated from the indoor premises and do not have loopholes (gun-slots). Four entrances—one located on each side of the building—and plenty of randomly built windows on the outside walls also reject the version that the castle was a defensive building.

There is an 11×11 meter square rectangular yard located in the middle of Kyrk-Kyz with long corridors (enfilades) leading to the entrance halls. These enfilades divide the entire complex into four independent blocks. Opinions on whether the yard was open or closed also differ. Elizaveta Nekrasova believes that it was roofed by a massive dome, which eventually collapsed, and the bricks were picked up by the people living nearby for their own needs.

There were two floors, with rooms located along the perimeter of the yard, and four sectors of the building; the total number of rooms and corridors reaches 52. The ceilings were up to seven meters high. Most certainly, one of the halls was a chillahona, i.e. a special solitary cell to “chill,” meditate, pray, and hold forty-day fasts. One of the rooms on the first floor was a dining hall as there were fragments of tandoors and dishes found there.

There is an air of a sacred building, one “that is open to everyone who seeks to comprehend God.”

It bears the symbols of the world, with the north/east/south/west concept, along with the concept of four elements: fire, water, earth, and air. This pattern is typical for the Zoroastrian temples of fire and is known as chortak, or “four arches” – a square dome pavilion with arches on four pylons with sacred fires. Open to all four corners of the earth, the castle is a symbol and a source of spiritual power.

It also bears some resemblance with an earlier tomb of the Samanid dynasty, which, despite its much lesser size, generally has the same structure – a cube on a flat plane, four entrances on the sides, and a hemispherical dome supplemented by small domes on the sides. But Kyrk-Kyz differs from other monuments with its brilliant brickwork and an amazing variety of arches and domes, which still preserve the purity and elegance of their forms and lines. There are various arches: triangular, oval and speary, as well as various domes. Because of this diversity, the castle is considered a real museum of medieval construction and technical practice.

The arches of Kyrk-Kyz. Photo taken by the author.

Finally, the most interesting thing about Kyrk-Kyz is that this exquisite beauty was built from simple sun-dried mud bricks, and the walls were plastered by clay. Baked bricks can be found only sometimes inside the arches. Wood was used to strengthen the walls and window area. Interior decorations were not preserved.

The brickwork impresses with its virtuosity. Photo taken by the author.

The aesthetics of the castle—bare massive clay walls with no fancy glazed ceramics of Timurids, combined with the decorated shadows of arches—is suitable for Sufi asceticism. But it remains deeply local, built from local construction resources. The land on the right bank of the Amu Darya, with its tugai forests, does not provide enough wood to bake bricks.

Sufi spirits

A central hall of the castle was likely to be a khanqah, a place where the dervishes’ worship rituals took place. It is hard to say today what they were like back then.

The Central Asian Sufi tradition is known by its vocal and quiet zikrs, and in the hall of a khanqah, a group of men would gather in the twilight of the dome space to perform the act of spiritual liberation.

Interestingly, the walls of the gallery leading to the main hall were painted in black. Pure carbon black was used for this purpose, which also links it with the Sufi practice. According to Sufi symbolism, black—the color of mystery and wisdom—meant spiritual liberation. In the beginning of their spiritual journey, the Sufis belonging to some tariqahs wore blue clothes, while those who reached the mystery wore black clothes to mark the path they traveled and their achievement of the absolute spirit.

Modern day residents—the locals—believe in the sacred meaning of Kyrk-Kyz, often coming here to pray and hope. An old shamanistic practice is used for making the wish real: pieces of old clothes are tied to the bushes growing on the ruins, people hope that the local ghosts will accept their sacrifice and make their wishes come true.

Shamanistic practice on the place of the Sufi zikrs. Photo taken by the author.

Termez was also important in Sufi history. It is in Termez, in the 19th century, that a famous Sufi named Al Hakim At Termiziy was born. Historians believe that he laid the foundation of the first religious dervish tariqah in the world. At Termiziy led an ascetical life, and because of this, he was highly respected by the locals. He became known in history because of his worldview, which was based on the appeal to humility, self-improvement through control over nafs (instincts), and suffering as a means to sanctification. In some way, his worldview had similarities with Buddhism, which, 10 centuries prior, had been the main religion in the Surhandarya region (between the 1st and 10th centuries).

Therefore, as much as we wanted, the Kyrk-Kyz, a Surhandarya castle, is not a story of 40 Amazons, even though the mystery of the name remains…