The Turkestan Album (Turkestanskii Al’bom—1871) was one of the great colonial photography projects of the 19th century.

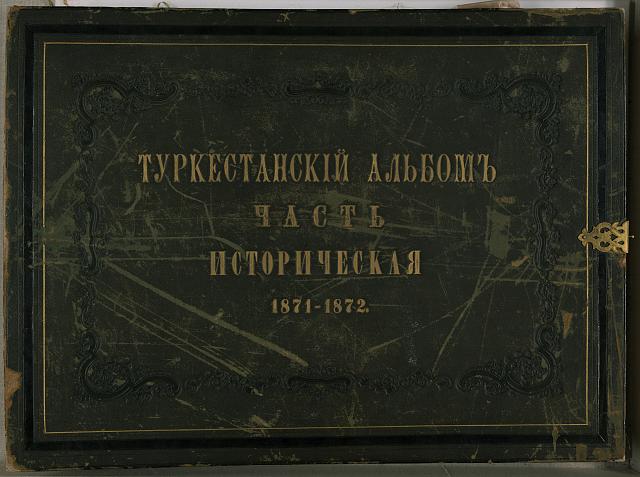

Commissioned by the first Russian governor-general of Russian Turkestan, Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman, it sought to package an exotic borderland which many felt had not been worth the expense of conquest, presenting it as a lavish gift to the Tsar and to educated Russian opinion. Thanks to the Library of Congress and the work of Heather Sonntag, it is also one of the most accessible visual sources of any kind on Central Asia: anyone with an Internet connection can scroll through the most comprehensive version’s 1,300 images, which have been divided into four sections—Archaeological, Ethnographic, Trade, and Historical.

Author

Alexander Morrison

Alexander Morrison is Fellow and Tutor in History at New College, Oxford, specializing in the History of Modern War and of the Russian Empire in Central Asia. He was previously Professor of History at Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan, Lecturer in Imperial History at the University of Liverpool, and a Prize Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. In 2012, he won a Philip Leverhulme Prize. He is the author of Russian Rule in Samarkand 1868–1910: A Comparison with British India (Oxford, 2008), and is currently completing a history of the Russian conquest of Central Asia, to be published with Cambridge University Press.

The two volumes of archaeological pictures contain the earliest photographic record of many of Central Asia’s great monuments, such as the mausoleum of Khwaja Ahmad Yasavi in Turkestan, and the tomb of Timur and the Shah-i Zinda in Samarkand.

The two “ethnographic” volumes reflect ideas of human biological classification that are highly reminiscent of the near-contemporary photographic collection “The People of India” (1868) and may indeed have been modeled on it. The single volume devoted to trades is a treasure trove for students of the artisanal crafts and commerce of pre-industrial Central Asia, though its original intention was to show just how prosperous and worthwhile an acquisition colonial Turkestan was. Yet it is the final, “Historical” volume that is perhaps the most curious and characteristic of the three. Unlike the others, which were compiled by the general editor of the album, the orientalist Alexander Ludwigovich Kuhn, it was the work of Mikhail Afrikanovich Terent’ev, then a young cavalry subaltern, who went on to become a Major-General and author of the standard history of the Russian conquest of Central Asia, which was published in three volumes in 1906.

This offers a clue as to the nature of the volume, which an unsuspecting viewer might expect to contain photographs of sites associated with the great events and individuals of Central Asian history—the sacking of Otrar by Chingis Khan’s forces, for instance, or the birthplace of Timur at Shahrisabz. Instead, over half the images in the historical album are of Russian soldiers, officers and men alike, staring grimly at the camera from behind their moustaches, their dark blue uniforms and kepi-like caps giving them a startling resemblance to Unionist troops of the American Civil War.

The remainder are images of fortresses and battlefields; colored plans of sieges, assaults, and battles; and a few photographs of Orthodox Churches, to illustrate the growing Russian presence. The “history” of the “historical” album is the history of the Russian conquest of Central Asia—that and only that. The significance accorded to towns, cities, hills, rivers, and other features of the landscape derives from the role they played in this narrative—one which in 1871 barely covered twenty years, and which would be prolonged through further campaigns of conquest in the 1870s and 1880s.

The men who featured in the historical album were those who had won the St George’s cross, the Russian empire’s highest decoration for valor, during a series of engagements which have today been largely forgotten, but which von Kaufman was anxious to develop into an epic worthy of the vast region over which he now ruled. There were certain clear elisions and omissions in this narrative, the most notable of which being that of the Russians’ Central Asian opponents, although a small number of Qazaq (“Kirgiz”) scouts who had served with Russian forces featured with their medals.

Another was the absence of any photograph of General Mikhail Grigor’evich Cherniaev, von Kaufman’s predecessor and the man responsible for the one episode that would live on in the Russian imagination: the capture of Tashkent, Central Asia’s largest city, in June 1865. There can be no question that this was deliberate: von Kaufman hated Cherniaev, who had never accepted his dismissal from Turkestan in 1866 and used his ownership of the newspaper Russkii Mir to mount repeated attacks on von Kaufman’s administration.

Instead, the historical section opened with a dramatic, Byronic portrait of Vasily Alexeevich Perovskii, who had fought at Borodino as a teenager in 1812 and became a favorite of Nicholas I. As governor of Orenburg, he had launched the disastrous winter expedition to Khiva in 1839, and then redeemed himself by capturing the Khoqandi fortress of Aq Masjid on the Syr-Darya in the summer of 1853. His portrait was followed by those of other senior Turkestantsy: von Kaufman himself; Gerasim Alexeevich Kolpakovskii, the governor of Semirechie province; Alexander Konstantinovich Abramov, governor of the Zarafshan region and veteran of assaults on Tashkent, Ura-Tepe, Yangi-Qurghan, and Urgut, who wore a black skull-cap to disguise a head wound; Dmitrii Nikolaevich Romanovskii, von Kaufman’s immediate predecessor as governor of Turkestan, who had in 1866 defeated the Bukharans at the battle of Irjar and captured Khujand and Jizzakh; and Nikolai Nikolaevich Golovachev, commander of the military forces of Syr-Darya province, victor over Bukhara at Chupan-Ata and Zirabulak, and later responsible for the massacre of the Yomud Turkmen during the invasion of Khiva in 1873.

What did these men have in common, other than their luxuriant facial hair?

With the exception of Romanovskii, who was in the region for less than a year, they all made a name for themselves through Central Asian conquest, and would spend the rest of their careers there. The choice of images laid out in the historical album was both a means of overlaying Turkestan’s landscape with a distinctively Russian historical narrative, and of emphasizing the degree of military skill and heroism that had been necessary to “unite” the region with Russia, thus advancing the careers of those who had led the campaigns.

The choice of images was both a means of overlaying Turkestan’s landscape with a distinctively Russian historical narrative, and of emphasizing the degree of military skill and heroism that had been necessary to “unite” the region with Russia

The album proceeded in roughly chronological order, focusing initially on Aq Masjid and the fortresses of the Syr-Darya line (established in the 1850s), then on the towns of the southern steppe—Toqmaq, Pishpek, Turkestan, Aulie-Ata, and Chimkent—which were captured in the early 1860s.

Then it was Tashkent (given, owing to the role of Cherniaev, rather less space than its importance warranted), Khujand, Ura-Tepe, and Jizzakh (1865-6). All these campaigns had taken place before von Kaufman’s appointment.

Almost half the volume (images 125-211) was devoted to the campaign of 1868 in the Zarafshan Valley, which von Kaufman had personally commanded and which had seen the ancient city of Samarkand fall into Russian hands. Photographs of the battlefields of Chupan-Ata and Zirabulak, showed where Bukharan forces had been routed. Every minor citadel in the Zarafshan Valley—Urgut, Penjikent, Kara-Tepe, Katta-Qurghan—had a dedicated photograph, even though in most cases the Russians had not suffered any casualties while taking these towns.

There were also a plan and photographs of the Samarkand citadel, where for five days in early June a small Russian garrison—including the famous Orientalist artist Vasily Vereshchagin, then a junior officer—had been besieged. The volume ended with the expedition to subdue the rebellious towns of Kitab and Shahrisabz in 1870, and Kolpakovskii’s capture of the upper Ili Valley, which had rebelled against Chinese rule in 1866 and been a concern to the Russians ever since.

It is clear enough how von Kaufman and Terent’ev wanted the album to be read, but what can historians working today glean from it?

Since it focuses on the assaults that marked the Russian advance, it provides an unrivaled visual record of these small market towns and fortresses, where in most cases no structures survive from this period—the citadels at Aulie-Ata (Taraz), Chimkent, Jizzakh and Katta-Qurghan are all long gone. While the portraits have the usual stiff quality of an era when long exposures were necessary, and there was no attempt to express character or emotion in them, the fact that so many are of the creased, weatherbeaten faces of ordinary soldiers—a group who otherwise rarely feature in photographs of the period—has an interest of its own.

The portraits of the officers also vary more than one might imagine, from the choleric, rather squat figure of Colonel Vasily Rodionovich Serov of the Ural Cossacks, hero of the Iqan affair of 1864, in which a single sotnia (company) held off a much larger group of Khoqandis, to the languidly exquisite figure of Captain Mikhail Karlovich Mazing of the Guards, decorated for his part in the capture of Jizzakh in 1866 and proud possessor (against very stiff competition) of what is surely the most magnificent moustache in the entire album.

There was a vast social gulf between these two figures—the former a career Turkestanets of humble background from the most “wild” and “Asiatic” of all the Cossack regiments, the latter a scion of the Baltic German aristocracy (related on his mother’s side to the von Ungern-Sternberg family) who grew up in St. Petersburg and served for just five years in Central Asia, making him what Turkestani officers called a fazan (pheasant), who flew in while there was campaigning, and hence a chance of medals, before returning to St Petersburg. Nevertheless, they are together in the album, each playing their part in the story of the conquest.

The creation of this elaborate, enormously expensive representation of the Russian conquest began long before the conquest itself was completed, and would continue into the early 20th century.

Turkestan was the making of many ambitious professional officers in the Russian army—it was the only unequivocally successful military campaign of the entire post-Crimean period, and von Kaufman and his successors did their best to ensure that it was celebrated as such until the fall of the Tsarist regime. What this narrative served to disguise was that, in purely military terms, Russian victories had mostly been very one-sided, often with little in the way of courage or tactical skill required of either officers or men. Nor was Central Asia anything like the unequivocal economic and strategic asset its conquerors made it out to be.

In the Turkestan Album, we see the beginning of a process of retrospective rationalization of this messier historical reality, one that is all the more striking for being in visual form.

The conquest of Central Asia was an unplanned, haphazard process, driven by Russian anxieties at being excluded from the European “Great Power” club, marred by bitter personal rivalries, and with its fair share of military reversals and logistical catastrophes. In the Turkestan Album, we see the beginning of a process of retrospective rationalization of this messier historical reality, one that is all the more striking for being in visual form.