During the first two “pyatiletka” (five-year plans) (1928-1937), Central Asian artists felt tremendous creative freedom and were bold enough to represent themselves “with brush strokes”—that is, in art.

Owing to its population’s high religiosity, the Zeravshan valley was hit hard by the cultural revolution in the USSR, a fact that later made it an interesting object of study for social scientists. Meanwhile, the ancient cities of Zeravshan provided beautiful inspiration for art.

Culturally speaking, the first five-year period in Soviet Central Asia was distinguished by two main features: the prevalence of women in the industrial workplace and the dissociation of peasants from religion and from the formerly influential kulak population. The Emirate of Bukhara (from 1920, the Bukharan People’s Soviet Republic) otherwise escaped the cultural revolution of the early Soviet years. There were no “philosophers’ ships” of exiled thinkers. Moreover, during the short period from 1920 to 1924, the Emirate of Bukhara became a hub for Turkic culture in Central Asia, bringing together such intellectual titans as the first Uzbek scholar, Fitrat (1886-1938); one of the most prominent Uzbek poets, Cho’lpon (1897-1938); the first Uzbek romanticist, Abdulla Qodiriy (1894-1938); and other future victims of Stalin’s repressions. During the period up to 1924, the region continued to be influenced by Islam, while private land ownership was preserved—two facts that had significant implications for culture.

Bukhara, which was both home to the region’s political leadership (Fayzulla Khodzhayev, the first Chair of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic) and its religious heart (as the capital of Islam in Transoxiana) provided a metaphorical canvas on which all these artists could come together.

After 1924, art in Bukhara began its remarkable transition from Ummah collectivism to proletarian collectivism. The first five pyatiletkas are best represented in Bukharan art by the works of four remarkable, yet not widely-recognized, artists. All of them could be featured on the pages of schoolbooks in today’s regional republics: Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and to some degree Kazakhstan.

These four individuals are Sadriddin Pochaev (1873-1948), known as “the last miniaturist of the East”; Nabidzhan Khafizov (1893-1959), the first Uzbek poster artist; the nobleman Sergey Yurenev (1986-1973), a historian of arts and Islamic studies who was repressed between 1942 and 1951; and Mikhail Kurzin (1957-1988), an avant-gardist exiled to Bukhara who served as chairman of Uzbek Association of Fine Art Workers and has the dubious distinction of being the only Soviet painter to be repressed three times (1923-1924, 1937-1946, and 1948-1954).

Sadriddin Pochaev

The son of a farmer and former shepherd, Sadriddin Pochaev was a jeweler by training. However, he was compelled to abandon his profession following the Soviet government’s monopolization of gold.

Pochaev was a miniaturist who created figurative images that combined the plots of classical Eastern poetry with architectural views of Bukhara. Pochaev created with a brush, using watercolor, gouache, and oil paint on plywood, paper, and papyrus.

He forged his own style, boldly revising ancient schemas and canons and borrowing painting techniques from other countries (such as India). His works lack pomposity and the images appear simplified.

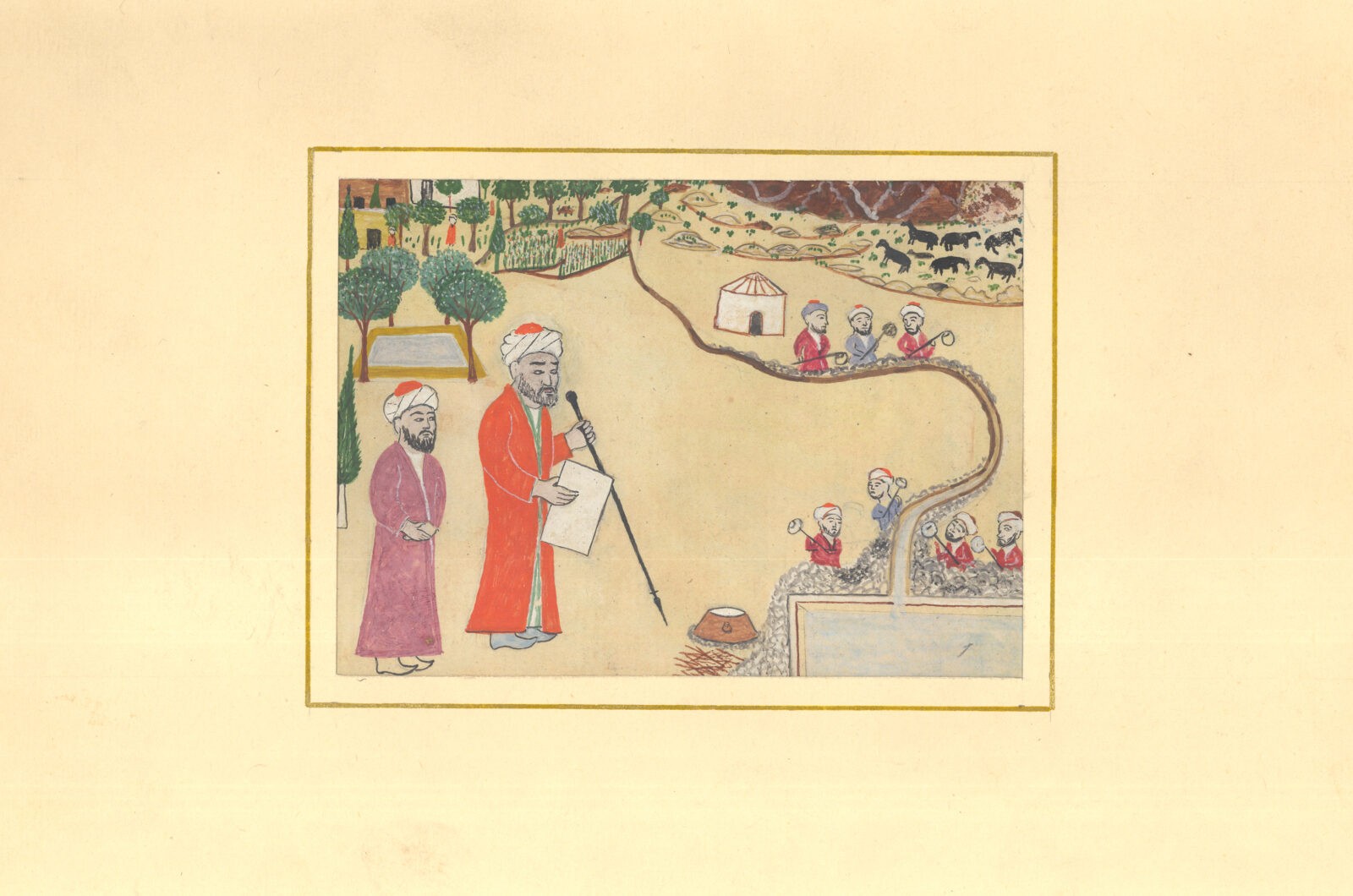

Sadriddin Pochaev. Series “Life and Works of Alisher Navoi,” (stored in the Bukharan art museum named for Kamoliddin Bekhzod)

In the miniature, named “Harvesting Cotton,” the author successfully conveys the energy of work during the collectivization epoch. The viewer can see a distinctive pre-Soviet gender division and feel a buoyancy of spirit and even mild irony.“Harvesting Cotton” walks the line between old art—the miniatures of chastity and modesty typical of the Bukharan school—and new art, which takes a linear, aerial perspective and focuses on socialist issues such as labor.

Pochaev’s art is not primitive; there are no deliberate simplifications. It is rather naive art, unique and amateur, linking traditional Bukharan miniature with socialist realism.

Nabidzhan Khafizov

During Soviet rule, painter-miniaturists and Arabic calligraphers were actively engaged in the creation of promotional, agitational-propagandistic works. They designed various banners with socialist slogans and decorated them with national prints. One such poster artist was Nabidzhan Khafizov.

In a brief biography that appears in the Uzbek National Encyclopedia, Nabidzhan Khafizov is referred to as “the first Uzbek poster artist,” with references to his famous posters “Pay taxes!,” “Communism—a huge cooperative. Join it!,” and “Cooperation—road to communism.” However, few of Khafizov’s personal works appear to have been preserved. Only three miniatures and one poster-miniature of his are stored in the Bukharan art museum. (Others may be in private collections.)

Khafizov may have been the most famous Uzbek poster artist of his day, but he was joined in his endeavors by other artists, including Mikhail Kurzin.

This miniature combines two apparently incompatible elements: traditional Eastern miniature and a proletarian plot. The plot is borrowed from the Soviet poster; the composition is grounded in the traditions of classical Eastern art.

Into the early Soviet years, the tradition of Central Asian miniature continued, reflecting the complex influences of different forms of Islamic art: calligraphy, carpet-weaving, ceramics, and silk-weaving. While Bukharan miniature, linked to such names as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (1455-1539), Makhmud Muzahhiba (1520-1560), Abdulla Bukhari (mid-16th century), was one-of-a-kind, in the early Soviet years it came to also be influenced by Palekh miniature, Armenian illuminated manuscripts, Kholuy miniature, and Kubachi art. The works of both Pochaev and Khafizov confirm that Soviet power succeeded in creating very vigorous art worlds in the Islamic regions of the USSR.

Pre-war Uzbek posters (authors: M. Reikh and S. Malt)

Bukhara’s artisans—in particular, a gold-embroidery atelier which engaged in carpet-weaving, curtain-sewing, tyubeteika, and chapans—had a particular place on the Soviet cultural landscape. Masters were true artists who were constantly creating new compositions and ornamentation for republican, all-union, and international exhibitions. This labor produced a specific type of painter.

In the artisan industrial atelier “Metkhanash.” Master Salomat Khodzhaeva (right) and Rosh Sabirov are busy embroidering tyubeteika (stored in the State Archives of Film and Documents of Uzbekistan; never before published)

At the same time, “individualistic” artists who did not find themselves a place in the new Soviet art sphere faced repressions. The memoirs of Dmitry Likhachov, who was imprisoned in Solovki prison camp on the White Sea–Baltic Canal, recall Bukharans exiled by Stalin who did not speak Russian and looked intellectual:

From the window…we saw how pampered Eastern people did something in their silky robes and silky high-heeled boots. Soon all these “basmachi,” as the bosses called them, died out, unable to withstand both cold and work.

Meanwhile, art in Soviet Central Asia was immensely influenced by the gradual and involuntary resettlement of intellectuals from other Soviet regions to the eastern ones.

Sergey Yurenev

A typical example of such “blood transfusion” in art is Sergey Yurenev, a law graduate of Leningrad State University and Moscow Archaeological Institute. A native of Vitebsk and a friend of Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935), and David Shterenberg (1881-1948), he taught modern Russian in the newly established Bukharan Higher Pedagogical Institute.

Nor was Yurenev alone in Bukhara. Many other nationals from all regions of the former Russian empire lived and worked there, among them the painter Anatoliy Bondarovich (1892-1975), the fine art experimentalist Lazar’ Lizak (1905-1974), the constructivist Moisei Ginzburg (1892-1946), and many other celebrities.

Yurenev forged a unique phenomenon in Bukhara: an intellectual salon that brought together many famous Soviet intellectuals and fostered a free-spirited, anti-colonial attitude that was open to the East and mostly opposed to the Soviets. Catholics, Orthodox, and Jews alike gathered in madrasas that were empty due to the advent of militant atheism and learned to speak the local Tajik dialect.

Mikhail Kurzin

Kurzin, who had an interest in ancient Chinese painting, introduced to the domestic school of art a principle of “black ink above everything else.” With it, he reached an unusual expressiveness of silhouette, which he primarily deployed in the form of posters for ROSTA (where he worked in tandem with Vladimir Mayakovsky).

Mikhail Kurzin has his own unique but underestimated role in the history of fine art in Central Asia.

Kurzin was one of the first to do public portraits, sketching people not only in city parks and squares, but also in the narrow crannies of old Bukhara.

Our discussion of Kurzin would be incomplete were we not to mention his wife, Elena Korovay (1901-1974), and her series of works about Bukharan Jews, which is a theme for another paper.

Of course, these are just a few of the many artists in Bukhara and other cities who worked along Socialist Realist lines. But through their efforts during the early industrialization and modernization pyatiletkas, these four figures—Pochaev, Khafizov, Yurenev and Kurzin—created the schools within which others would later work. These followers include a watercolorist, Marat Sadykov; a miniaturist, Davlat Toshev; an artisan, Khamro Rakhimova; a ceramicist, Ibodullo Narzullaev; a blacksmith, Shakir Kamalov, a painter, Erkin Dzhuraev; and many others.

The spirit of the period might be felt through the song “On the way to the factory,” by the remarkable Uzbek-Tajik composer Mukhtar Ashrafi (1912-1975), who had geographical ties to Pochaev, Khafizov, Yurenev, and Kurzin.