Debates over the new Kazakh Latin alphabet have united Kazakh- and Russian-speaking communities, both of which have taken to the web to criticize what they consider an inappropriate alphabet. In light of this opposition, the initial “apostrophe” alphabet was not accepted; Kazakhstan is currently awaiting the next version of the Latin alphabet for Kazakh, the state language, which is supposed to be transferred from the Cyrillic script by 2025.

Author

Diana T. Kudaibergenova

Lund University/Cambridge University

is a political and cultural sociologist working on social theory of power, nationalism, law, and elites in a comparative and historical perspective. Her first book, Rewriting the Nation in Modern Kazakh literature (Lexington, 2017) deals with the study of nationalism, modernisation and cultural development in modern Kazakhstan and her forthcoming book focuses on the rise of nationalising regimes in post-Soviet space after 1991.

On October 26, 2017, President Nursultan Nazarbayev signed a decree to transfer the Kazakh language from Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet. The decree calls for Kazakhstan to transition Kazakh, the state language, into a version of the Latin alphabet by 2025. This long-awaited “Latinization” will occur gradually, but many local brands are already printing their names in the Latin alphabet: Qazaq Bank and Qazaq Air, for example.

Kazakhstan has long sought to transfer the Kazakh language from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet: President Nazarbayev stated in early October 2017 that the idea of transferring the Kazakh language to the Latin script “has always been on our minds ever since independence” in 1991. The “Latinization”—as it was dubbed on social media and online—of the Kazakh language is seen by many Kazakh-language supporters as a long-awaited move away from the domination of the Russian intellectual and cultural sphere.

It is also perceived as an opportunity to unite the Kazakh diaspora on a written level. Kazakh is a Turkic language with its own specific sounds, some of which can be found in the Latin alphabets of the Turkish, Azeri, Uzbek and Turkmen languages.

It is the official language of Kazakhstan, where approximately 70% of the population claims speaking knowledge of Kazakh. In addition, Kazakh is spoken by minority communities in China, Mongolia, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Germany, and other places where ethnic Kazakhs live. However, the different alphabets used for the Kazakh language currently divide these communities.

It is also perceived as an opportunity to unite the Kazakh diaspora on a written level. Kazakh is a Turkic language with its own specific sounds, some of which can be found in the Latin alphabets of the Turkish, Azeri, Uzbek and Turkmen languages. It is the official language of Kazakhstan, where approximately 70% of the population claims speaking knowledge of Kazakh. In addition, Kazakh is spoken by minority communities in China, Mongolia, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Germany, and other places where ethnic Kazakhs live. However, the different alphabets used for the Kazakh language currently divide these communities.

Ethnic Kazakhs in China write Kazakh in the Arabic script that was used in Soviet Kazakhstan until 1927, when Kazakh was transferred into Latin script. Other communities transliterate Kazakh into more Turkish spelling.

These differences create a situation in which different communities of ethnic Kazakhs and Kazakh speakers cannot read the same texts or enjoy the same literature; every text must be “translated” into the appropriate writing system. As such, Kazakhstan’s Latin alphabet project has the potential to serve as a unifying platform for many millions of Kazakh-speakers across the world. It could also create a space for common space for written literature and online networks in Kazakhstan and in the diaspora. Both of these cultural and social spheres are increasingly important for the development of spoken Kazakh and for enhancing further connections between all of these communities. The new Latin alphabet was seen by many Kazakh speakers in Kazakhstan as a great step towards the development of the state language use.

However, the first version of the proposed alphabet was a great disappointment to the public. Criticism of the work of the working committee on the language project began even before the so-called “apostrophe alphabet” was revealed in October 2017.

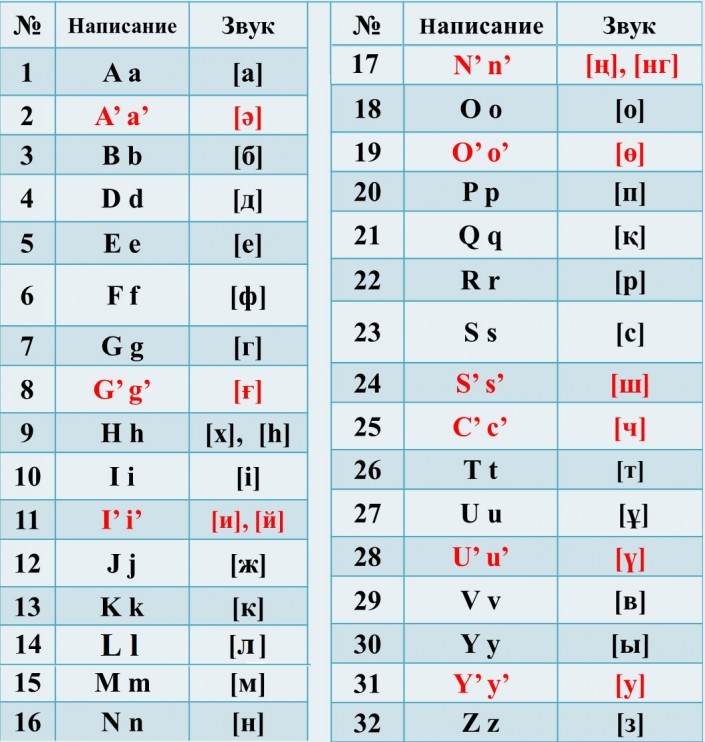

To date, there are at least five official modes of transliterating Kazakh language from Cyrillic to Latin script, including the ALA-LC Library of Congress transliteration. But the language committee in Kazakhstan aimed to produce its own version that did not depend on previous transliteration tables. It therefore created a new alphabet featuring 23 Latin letters, along with 9 specific Kazakh sounds, which were identified by placing an apostrophe after the letter (see Figure 1 from Presidential Decree 569).

Though the work of the committee—and the selection of its members—was rather obscure, president Nazarbayev stressed the importance of popular discussion of the new alphabet, describing it as something “no other country” had done before. In early October 2017, the president met with the working committee, discussing the more than 300 letters directed to the presidential administration on the matter. In December 2017, a number of well-known Kazakh-speaking academics and professors addressed another resonant letter to the president, asking him to prevent the transition to the “apostrophe” alphabet. They argued that the move would complicate the writing system and only diminish the status of the Kazakh language in the country. The letter was a response to the published version of the alphabet, which the Kazakhstani online community first mocked for the word “saebiz” (transliterating the Kazakh word for “carrot”); concerns were later raised about the “garbage” apostrophe alphabet that required multiple apostrophes in one word to separate Kazakh-specific sounds, such as in the word s’yg’ys’ (east).

As soon as the “apostrophe” alphabet was revealed, online debate ensued. Kazakhstani citizens criticized this proposed version of the alphabet, which many considered “hastened,” “alien,” and frankly “inappropriate” for the Kazakh language.

Those who supported transferring the alphabet to Latin script opposed apostrophes; a few voices on the margins also disapproved of the alienation from the Russian (Cyrillic) sphere. Why were these discussions important?

The internet is one of the most important spheres for Kazakh culture worldwide. Kazakhstan has one of the fastest-growing communities of mobile internet users, with more than half its population regularly using mobile internet (over 9 million people in 2016). Global social networks such as Facebook and Instagram are very popular among the country’s users. Many local analysts have framed Facebook as Kazakhstan’s version of digital civil society; there are also numerous anecdotes about bilingual networking and the spread of news on the popular WhatsApp chatting application. The spread of mobile communication—which, due to the configuration of cell phones sold in Kazakhstan in the early 2000s, initially meant typing messages in Latin script—forced many young people to undertake their own transliteration of the Russian and Kazakh languages. In popular forums such as chatrooms, and thanks to the “SMS revolution” of the mid-2000s, the Kazakh and Russian languages both enjoyed widespread informal transliteration that produced all sorts of iterations of the specific sounds and letters absent from other languages.

All this informal transliteration of Kazakh language existed online for more than a decade. By the time the “apostrophe alphabet” was revealed, the digital realm had already undertaken heated discussions about the spelling of the country’s name—should it be “Qazaqstan” or “Kazakhstan”?—and even created its own transliterations for tribal identities: T-shirts, notebooks and baseball caps were emblazoned with “Nayman” or “Kerei” depending on the tribe.

By the time the “apostrophe alphabet” was revealed, the digital realm had already undertaken heated discussions about the spelling of the country’s name—should it be “Qazaqstan” or “Kazakhstan”?

Many Kazakh online resources, such as kitap.kz and abai.kz, not only serve as repositories of Kazakh language literary and cultural texts, but also provide a discussion platform for problems faced by the growing Kazakh-speaking sphere in Kazakhstan. It is not unusual to see a Kazakh transliteration of the comments, discussions or slogans on these sites, as well as those on Instagram and YouTube. As the online presence of the Kazakh language grows, so too does its transliteration.

The Kazakh language has become the dominant language of secondary education in Kazakhstan, with more than 70% of secondary schools teaching in Kazakh, even in the predominantly Russian-speaking areas of northern and eastern Kazakhstan. Yet the Russian language remains widely used in the public sphere, and discussions about transferring the Kazakh alphabet into Latin script have raised concerns among the country’s Russian-speaking population. President Nazarbayev explicitly stated that “The transfer of the Kazakh language to the Latin alphabet does not interfere with the rights of the Russian-speaking population, nor the rights of the Russian or any other language. The use of Russian language in Cyrillic will continue. Russian will continue to function.” The President did not mention the role this alphabet would play for the so-called “cosmopolitan” Kazakhs, who are predominantly Russian- and English-speaking.

Asel Kadyrkhanova, a Kazakh contemporary artist and the creator of a work of art dedicated to the memory of Stalinist terror victims, spoke out about the “apostrophe” alphabet in a very poetic way. She posted a long and emotive text on her Facebook page describing her childhood memories of learning the specific sounds of Kazakh and trying to translate Abai, a nineteenth-century Kazakh philosopher and poet, using two different dictionaries. One Kazakh-Russian dictionary was “useless,” as it barely attempted to translate anything into Kazakh; the other was incomplete. This story clearly illustrated the realities of the transition period from the Soviet Union to independent Kazakhstan: due to the absence of appropriate tools, dictionaries and Kazakh language manuals, many people, not only texts, got lost in translation.

Asel Kadyrkhanova’s post was written in Russian and was shared 70 times, a significant number for the Kazakhstani Facebook sphere. The level of discussion of this post is unprecedented: for the first time since independence, it seemed to give the young generation of both Kazakh- and Russian-speaking communities in Kazakhstan the chance to discuss their ambiguous national identity. Why is it ambiguous? Because Asel Kadyrkhanova, like many young people who grew up in independent Kazakhstan, was subjected to the Soviet notion of “nationality,” where ethnicity is connected to the mother tongue. Identification with the Kazakh language—rather than proficiency in it—defined one’s ethnic and socio-cultural identity. The transfer to the Latin alphabet bares the identity problems that this Soviet legacy leaves to bilingual Kazakhs, non-Kazakh-speaking Kazakhs, children of mixed ethnic background, and those young people who, regardless of their ethnicity, speak a foreign language (not Russian, but English) better than Kazakh. These people are labelled “shala Kazakhs,” or even mankurts, by Kazakh nationalist groups. Very few Kazakh nationalists actually understand that “shala” and “mankurt” labelling is the legacy of Soviet domination and the Stalinist definition of nations (connecting language, territory and ethnic group) that they condemn. All in all, the new alphabet inevitably directs attention to the legacies of the Soviet Union, unsolved problems of socio-linguistic and cultural-linguistic identification, and failed policies to promote Kazakh in an original or exciting way rather than forcing it on a complex milieu of Russian-speakers.

Discussions of the new alphabet for Kazakh language demonstrate a number of important trends in Kazakhstan. The divides in linguistic spheres—between the so-called Kazakh-speakers, shala Kazakhs (Russified ethnic Kazakhs) and Russian-speakers—are brought to the fore. These divisions become even more visible when anti-apostrophe discussions are more pronounced in Russian language. Nevertheless, these different linguistic communities are able to unite behind a common cause: protesting against this new version of the alphabet. It is important to note that many of Kazakhstan’s Russian-speakers supported transferring the Kazakh language to the Latin alphabet but criticized the “apostrophe” version: these individuals expressed their dissatisfaction by transliterating their last names, as with the famous meme of S’is’kin for Shishkin. Social networks and online resources continue to play an important role in influencing the mediascape in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan’s citizens have created their own networks of influence on Facebook, and when it comes to such important and resonant discussions as the debates over different versions of the new Latin Kazakh alphabet, news agencies cite popular Facebook users and internet bloggers. The Kazakh-language internet sphere is also growing rapidly, occupying an important sphere within online social networks. This mediascape is complex and heterogenous.

The collective discontent shared online can foster positive dialogue with the governing bodies. In early December 2017, Senate speaker Kasymzhomart Tokayev announced in the Parliament that it was too early to talk about using the “apostrophe” version of the new Kazakh alphabet, indicating that the committee was discussing a newer and more appropriate version of the alphabet. He subsequently shared this news on his popular Twitter account in Russian and Kazakh language; both messages used the Cyrillic script. Meanwhile, Kazakhstanis have again taken to the internet, this time to discuss yet another divisive theme, uyat (from the Kazakh word for “shame”), but that’s another story…