From October 10 to October 13, the George Washington University’s Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies hosted the “Crafts and Couture from Central Asia” festival. The festival was organized during the 20th Annual Central Eurasian Studies Society Conference (CESS 2019). This cultural event brought together artisans from Central Asia and private collections from both the U.S. and Canada, displaying a wide range of symbols and designs of Central Asian clothing, Turkmen carpets, Uzbek suzani, Kyrgyz felts, and Kazakh silver ornaments.

Combining a centuries-long legacy with modern designs, the festival aimed to showcase the skills and knowledge of Central Asian artisans—many of whom struggle to bring their products to Western markets.

Snejana Atanova, curator of the event, presented a quick overview and description of some of the artifacts and objects that were displayed at the festival.

Turkmen Tekke overcloak, ýaşyl çyrpy. Silk lacing stitch on silk fabric ketene, Turkmenistan, early 20th century. Collection of Catherine Cosman

This overcloak is usually worn by a young bride on her wedding day and then during the first month after the wedding. The embroidered tree of life on the ýaşyl çyrpy symbolizes fertility, perpetual continuity through generations, and even immortality. This garment is still highly popular in Turkmenistan.

Parandja. Silk-hand embroidery; applied handwoven, silk trim; silk tassels; cotton lining. Ferghana Valley, early 20th century. Collection of Asyl and Charlie Undeland, entitled “Kurak: A Central Asian Patchwork”

The parandja is a capelike garment with long false sleeves that were fastened together and hung down the length of the back. It is accompanied by a black, waist-long veil, known as a chachvan and woven out of horsehair. This garment completely enveloped the wearer and draped her head. According to travelers’ accounts, the parandja was worn in Central Asia until the 1930s.

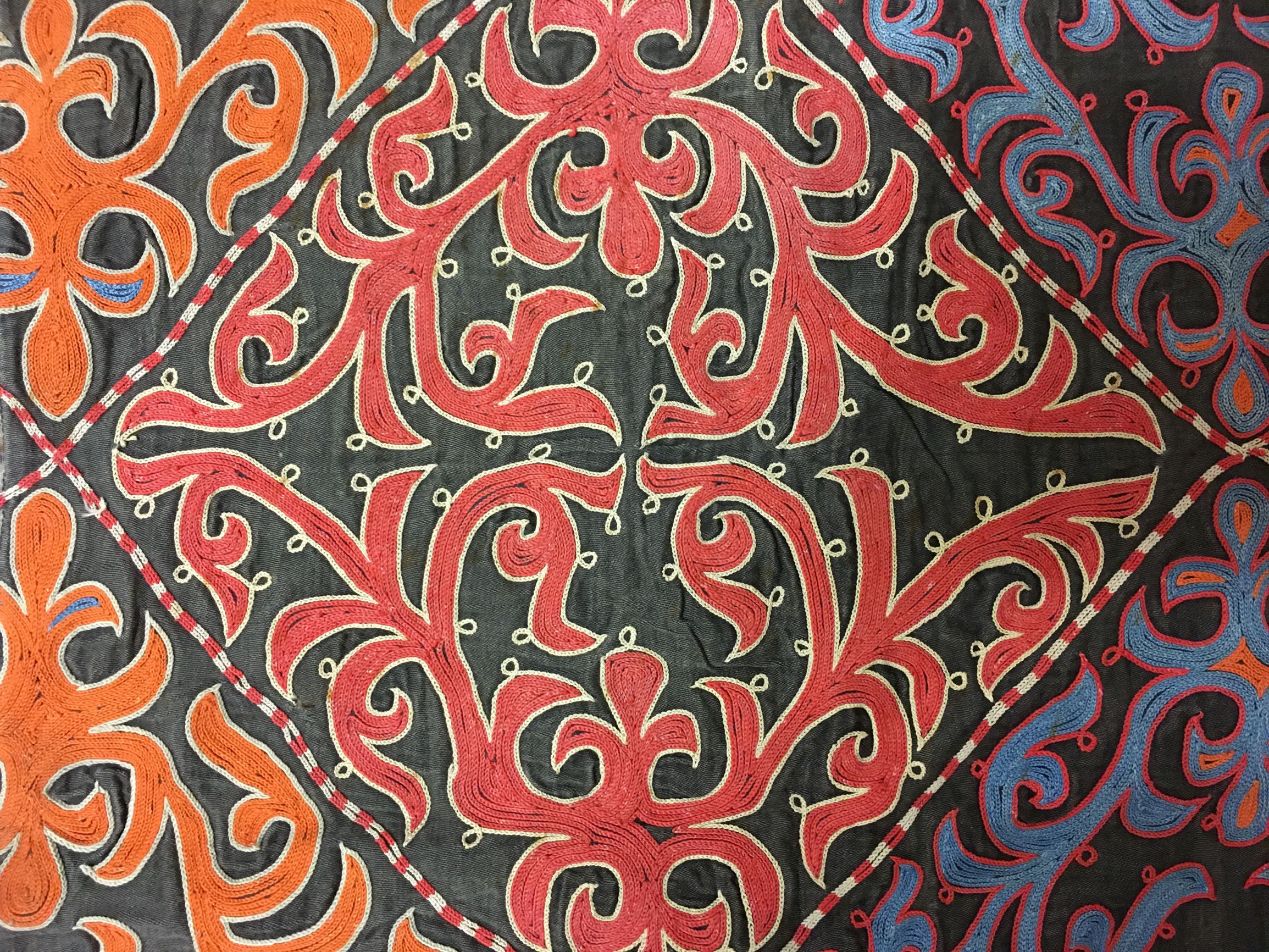

Shyrdak. Handmade felt carpet with applique stitching. Northern Kyrgyzstan, 1970s. Collection of Asyl and Charlie Undeland, entitled “Kurak: A Central Asian Patchwork”

The colorful shyrdak has become an integral part of Kyrgyz identity. In 2012, “Ala-kiyiz and Shyrdak, art of Kyrgyz traditional felt carpets” was inscribed to the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritages in Need of Urgent Safeguarding. The making of Kyrgyz felt carpets is inseparably linked to the everyday life of nomads, who used felt carpets to warm and decorate their yurts. Creation of felt carpets demands unity among the community and fosters the transmission of traditional knowledge—generally from older women, who are concentrated in rural and mountainous areas, to younger women within the family.

Chapan (woman’s robe). Adras ikat, silk warp and cotton weft. Russian-printed cotton lining. Ferghana Valley, late 19th century. Collection of Asyl and Charlie Undeland, entitled “Kurak: A Central Asian Patchwork”

Adras is a heavy, plain-weave fabric, and the Malay-Indonesian word “ikat,” or Central Asian term “abr,” refers to the fabric pattern. According to Susan Meller, most of the 19th century ikat was produced in Bukhara and the Ferghana Valley.[1]

Chach kep or kep takiya, a soft cap with embroidered earflaps and plait-cover. Atlas, silk lacing stitch on plain weave cotton, silver ornaments. Southern Kyrgyzstan, early 20th century. Collection of Asyl and Charlie Undeland, entitled “Kurak: A Central Asian Patchwork”

The plait-cover hides a woman’s long braids, which may attract the evil eye, and the silver ornaments ward away any evil spirits. Chach kep, or kep takiya, is accompanied here with an embroidered scarf called a duriya, and kyrgak, embroidered details on the turban.

Tus Kiiz. Cotton chain stitch embroidery on cotton ground, velvet. Kazakh Area of Western Mongolia, the mid- 20th century. Collection of Professor Sean Roberts

Tush kiyiz. Fine chain stitch on cotton Northern Kyrgyzstan, early 20th century. Collection of Asyl and Charlie Undeland, entitled “Kurak: A Central Asian Patchwork”.

These large textile wall panels were part of the interior decoration of many Kyrgyz and Kazakh homes. They were hung in the place of honor, along the back wall of the yurt, facing the entrance.

Baby cradle cover beshik–push. Hand embroidered silk with a cotton chain stitch, or basma, on cotton ground. Samarkand, mid 20th century. Collection of Professor Sean Roberts.

A traditional baby cradle was crafted of wood with a horizontal turned handle. A beshik-push was draped over the top rail to keep out any evil spirits, and the embroidered ornaments provided additional protective function.

Düýe başlyk camel trapping. Printed and plain cotton, wool, and silk. Yomut Turkmen, early 20th century. Collection of Catherine Cosman

The düýe başlyk was made to adorn camels during a wedding ceremony. It is draped over the camel’s head, with patchwork panels hanging down each side of the camel’s neck. Feathers, triangle-tumars, and buttons are talismanic, to protect against all evil, fatalities, threats, and trouble.

A detail of Turkmen salor çuwal. Wool, natural and synthetic dying, short velvety pile. Early 20th century. Collection of Professor Sean Roberts

The saddlebag, or çuwal, was used by Turkmen nomads as a means of transporting baggage or as part of a yurt interior. A variety of bags were woven by a young bride for her dowry.

An exceptional Bukhara coat. Samarkand. Late XIX-early XX century. Collection of Marilyn and Marshall R. Wolf (on the left). Ikat kurta. Silk warp, cotton weft. Samarkand, Late 19th – early 20th century. Collection of Marilyn and Marshall R. Wolf (on the right)

Coat made in ala-kiyiz, or wet-felting technique. Felt and silk. Kyrgyzstan. Artisan Farzana Sharshenbieva

Boots. Handmade embroidery, silk and cotton, velvet lining. Turkmenistan. Artisan Leyli Khaidova

Jewelry with natural stones. Kazakhstan. Silversmith Serzhan Bashirov

[1] Susan Meller. Silk and Cotton Textiles from Central Asia. New-York, 2013. p. 55