The history of modern Tajik art history rarely mentions the existence of a naive trend in the country’s fine arts.

However, in her introduction to the publication Essays on the Artists of Tajikistan, one of the most famous art historians of Tajikistan, the late Lutfiya Aini (1934–2015)—the youngest daughter of the founder of Soviet Tajik literature and prominent public figure Sadriddin Aini (1878–1954)—casually mentions the work of painter A. Kamelin displayed at a 1961 exhibition of Tajik fine arts, writing that “his works combine the academic solution of composition in a painting, understood as an expanded three-dimensional space of stage action …. with a touch of primitivism as a style, as an immediacy of world perception.”

Despite the official statement that naive artists are not prevalent in the country, they still exist. The objective of this work is to define naivety in the visual arts of Tajikistan as a form of self-expression by artists with a high level of artistic education.

Almost all Tajik artists of the Soviet period were educated in the key art universities of the former Soviet Union: Moscow, Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Vilnius, etc. Since then, all active visual artists have been educated at the National Art University named after Mirzo Tursunzade. Despite their premier education, they consciously use primitivistic approaches in their artistry. This may be considered inevitable in the sense that the social order forces artists to apply naivety in their work in order to indicate their reflection on reality and document the current state of society.

Author

Lolisanam Ulugova, pictured with visual artist Murod Sharifov’s (b. 1984) canvases “Cow,” 110х110, c/o, 2010. and “Bull,” 110х110, c/o, 2010

Lolisanam Ulugova

Lolisanam has been an art manager in Tajikistan since 2000. She has contributed to writing and producing the nation’s first 3-D animation film, a short designed to promote awareness of environmental issues among children. She holds a Master’s degree from the University of Turin, Italy and an undergraduate degree in Russian Language and Literature. She was a Global Cultural Fellow at the Institute for International Cultural Relations at the University of Edinburgh and participated in the Central Asian-Azerbaijan (CAAFP) fellowship program at the George Washington University at Elliott School of International Affairs for Fall 2019.

Preface

Art critic Rauf Muradov (1939–2015), in his preface to the album of the visual arts of Tajikistan, writes that “After the Arab invasion, rock paintings, monumental murals of Penjikent, Shahristane and Ajinateppe historic sites gradually began to disappear and subsequently almost completely ceased to exist. This was due to the spread of Islam, in particular its denial of the possibility of perceiving a deity in the form of a visual image, which served as the basis for the persecution of idolatry and icon painting. Later, zealous adherents of Islam extended this ban to depictions of people and animals.”

In spite of these prohibitions, the creative energy of people cannot be stopped, so all thoughts or reflections on reality have turned into ornaments of decorative art that metaphorically describe the life around them.

Nature remains the main theme of visual art. Muradov mentions “the special passion of artists for depicting nature, the multifaceted use of landscape motifs that help to reveal the ideological content of the work. This passion for landscape has its own historical and social roots. This was influenced to a certain extent by the traditions laid down in the first years of the development of Soviet fine arts in Tajikistan. Constant and deep communication with nature has developed among Tajik artists a certain structure of the plein air language of painting, which distinguishes their works.”

Besides a craving to display nature, there was and continues to be a desire to use elements and patterns of traditional Tajik culture. In addition to natural landscapes, almost all the works of modern Tajik artists are filled with elements of decorative and applied art: whistles in the shape of dragons, clay and rag toys, earthenware and glazed national dishes of various shapes, decorated bowls and vases, metal jugs… Looking at the country’s decorative art, one can learn about the soul of the people, their ideas about beauty and goodness, their fantasies and dreams.

An important type of visual art that developed under the Islamic prohibition on depicting the human image was Kundal, an ornamental painting technique. Here, each image becomes an element of an ornamental composition that focuses on geometric motifs. Kundal involves the application of gilt and silver paint to a relief clay base and was widely used in architecture as well as in panels/paintings. The cross and the swastika were of particular importance in Tajik culture, expressing harmony and health. The swastika had a special significance in the culture of the ancient Tajiks, denoting the four elements of nature (water, soil, air, and fire). The triangle was the symbol of a woman, hence why applied arts feature many triangle-shaped amulets.

One must also mention woodcarving as a significant form of folk applied art. Woodcarving attained a high level thanks to the skills of amateur artist Sirojiddin Nuriddinov (1919-1995). Ideologically, his panels reflected the Soviet reality, but he made portraits of the poets and heroes of Persian literature. In his works, he employed traditional forms of oriental architecture and ornamental art. The main achievements of the artist’s work were elevating the craft of woodcarving to the status of fine art and giving it the grace of sculpture.

Artists

Naive techniques are used by many artists in Tajikistan, including Farrukh Negmatzade, Akmal Mirshakar, Vladimir Glukhov, and Maksud Mirmukhamedov.

Farrukh Negmatzade (born 1959) is one of the brightest representatives of the country’s fine arts. The artist has experimented with all genres and styles of fine art: abstract (early works), nude (Green and Orange, Blue and White exhibition in 2004), and monumental (Red and Gray series reflecting the Soviet past and present of the country). Since 2005, he has painted rural landscapes, depicting rural life through the eyes of a city dweller. Significantly, this series of works—seasonal landscapes featuring individuals who look similar to cartoon characters—has become popular and enjoyed commercial success.

The naive element of childish or cartoony characters has made his signature style recognizable among the country’s art community. Looking at his paintings, one can understand how the country lives now. The artist often goes to bazaars, mosques, and kishlaks (villages) to collect material for his work. Reflecting the social situation on the ground, he rarely mixes female characters with male characters.

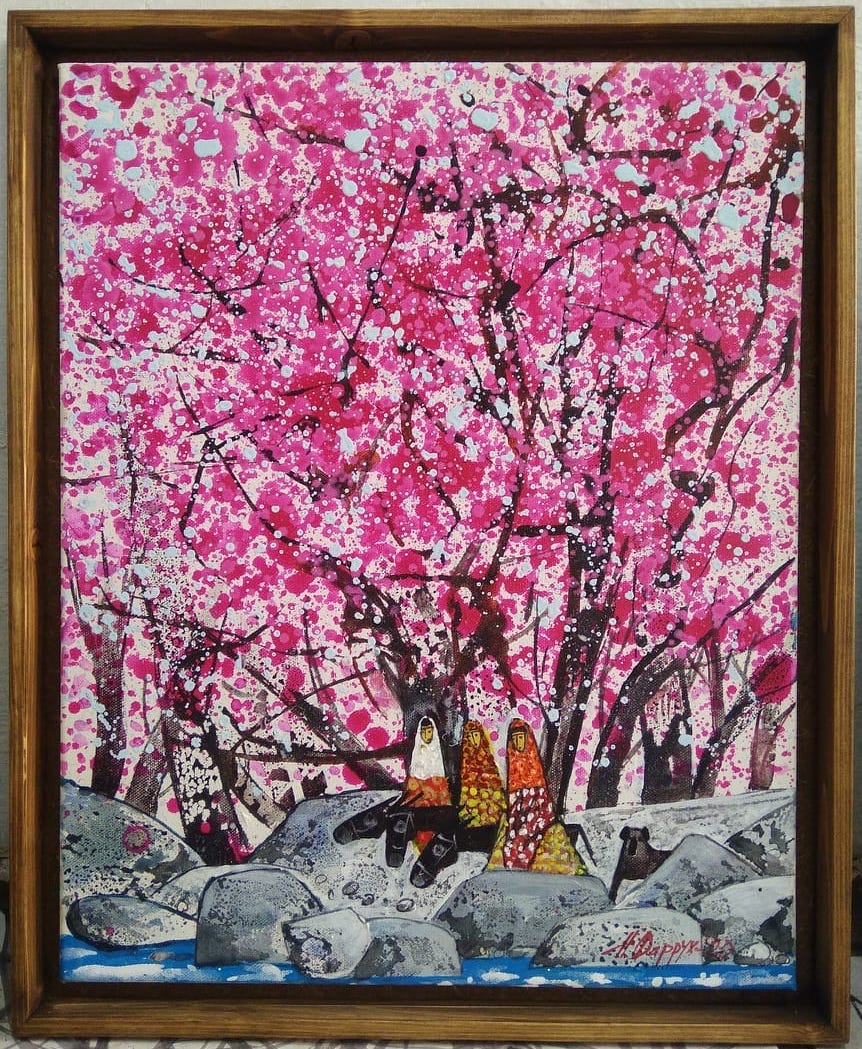

Akmal Mirshakar (born 1961) is the youngest son of Mirsaid Mirshakar (1912–1993), a famous poet and public figure of Soviet Tajikistan. The artist is a colorist, applying a sense of humor to the decorativeness that reflects the reality of his country. His people have similar faces to those in medieval frescoes, as if they have descended from those canvases to visit his country. Female figures wear dry expressions, likely reflecting the worries and hardships of life. In his few (mostly early) works depicting men, their faces are full of anxiety. His female images are resonant with a sense of perseverance and vitality: they are in a constant hurry, whether on their way to visit someone or to shop. Mirshakar may have been the first in Tajikistan to use Warhol’s portrait of actress Marilyn Monroe on his canvases.

Despite the traditional way in which he depicts his characters, he is extremely modern. His work keeps its finger on the pulse, focusing on the synthesis of modernity and archaism as a defining characteristic of his society.

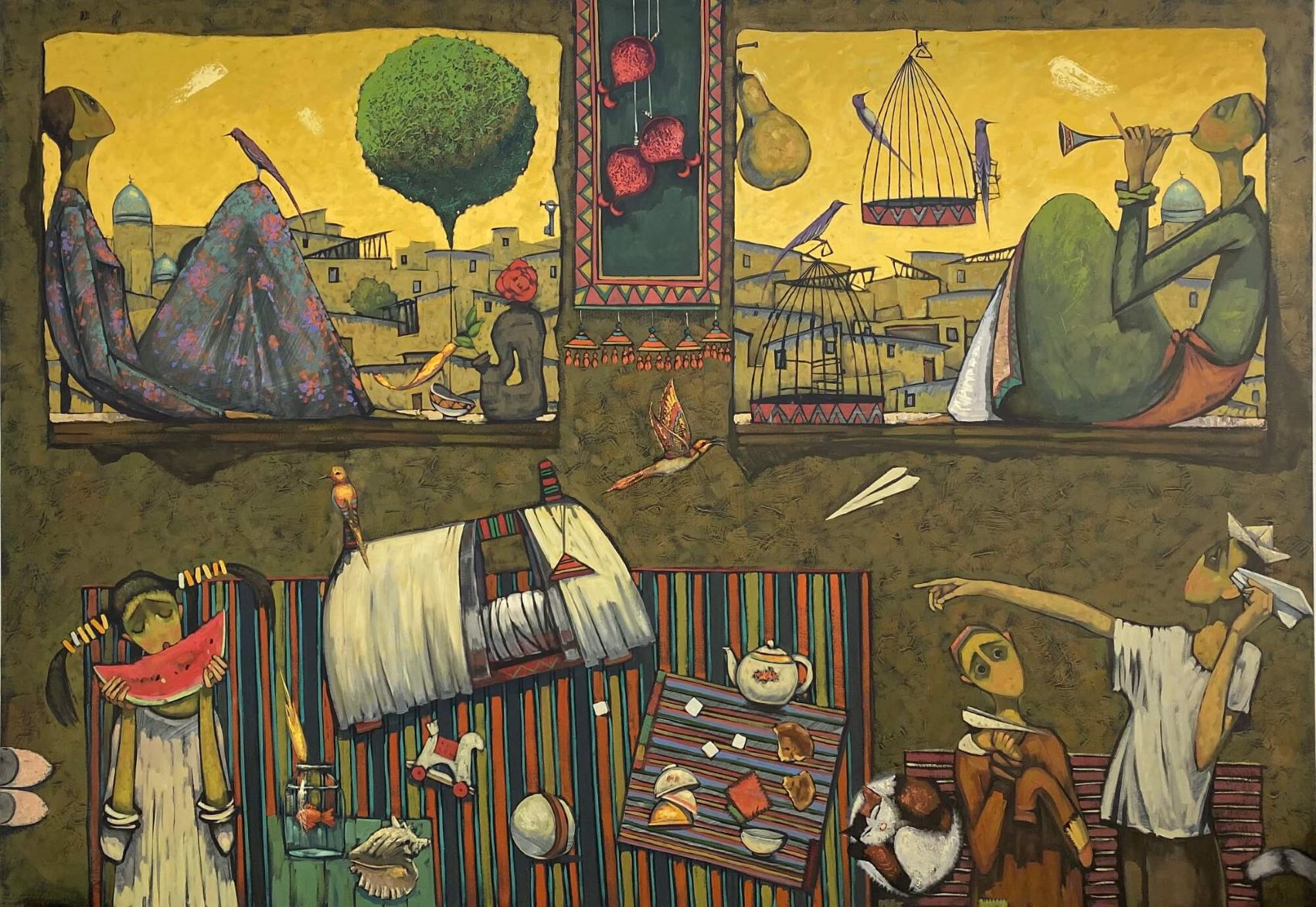

Maksud Mirmukhamedov (born 1986) quickly moved away from the canons of academicism and became serious about decorativeness, boldly using elements of traditional culture and primitivism. The artist deploys the whole range of signs and symbols that abound in Tajik culture, including the pomegranate, a symbol of family—and fertility, without which a family in the traditional sense is not possible; the bird, a poetic symbol of love or the soul of a beloved who has flown in to talk with his beloved; and the cage, which represents a trap or obstacles to freedom.

All Mirmukhamedov’s works are about himself, his family, and the people that surround him. Thinking about children as a continuation of himself and the family is the fundamental theme of his work.

Vladimir Glukhov (1961–2018) was a Russian-Tajik artist who absorbed all the colors and shades of the nature and culture of Tajikistan. His characters are fantastic, unrealistic, and funny, full of the grotesque and humor. The artist purposely indicates an exaggeration of reality, a reflection of his invented reality. It has been said that “The features of European Fauvism are manifested in the works of Vladimir Glukhov. The color symbolism inherent in his work, combined with elements of folklore, gives contemporaries a reason to call the artist ‘Russian Gauguin.’” Although I personally do not see Gauguin in this artist, I do see him as a bright representative of naive art.

Conclusion

Summing up, I would like to emphasize that the term naivety has a negative connotation and should be replaced, on the recommendation of Tajik artists, with a more accurate description of artists’ works. In fact, it is the norm for highly skilled artists to use techniques of primitivism and move between academism and primitivism. Naivety is not only a direction of primitivism, but also a state of mind in which an artist sometimes allegorically, sometimes realistically, softly, exaltedly conveys the reality he has seen. The artist uses a different metaphor, employing the rich traditional culture of a people whose semiotics is full of various signs, symbols, and hints.

Artists in Tajikistan are well aware of the importance of the visual naivety of artistic expression. They may even naively believe that the allegorical nature of their works will be understood among the younger generation. The most important thing is to recognize that naivety is not superficial, frivolous or sugary, but an equal direction for artistic self-expression in the country. With this vital recognition, Tajik artists can take their place among the global naive art community.

Acknowledgments:

i. Artist Karim Nazhmiddinov (born 1958)

ii. Art critic Larisa Dodkhudoeva (born 1947)

iii. Public figure Ilkhom Abdulloev (born 1977)

iv. People’s artist of the Republic of Tajikistan Savzali Sharipov (born 1946) and his son,

v. Artist Murod Sharipov (born 1984)

References:

1) Lutfiya Aini, ed., Essays on the Artists of Tajikistan (Dushanbe: Donish, 1975), 21.

2) Law of the Republic of Tajikistan on Public Finance of the Republic of Tajikistan No. 946, March 19, 2013.

3) UNESCO and IFES, “Art and Aesthetic Education in the Republic of Tajikistan: Issues and Prospects for the Development of Creative Abilities in the XXI Century” (Dushanbe, 2010).

4) Rauf Muradov, foreword, Landscape of the Mountainous Region (Dushanbe: Irfon, 1986).

5) A.A. Tikhonova, “The Symbol of the Swastika: Archetypal Meaning, History and Modernity,” Vestnik MGUKI 6 (68) (November-December 2015).

6) Larisa Dodkhudoeva, Tajik Graphic Art and Sculpture of the 20th Century (Dushanbe, 2006).

7) Firuz Ulmasov, ed., Tajik Art (Dushanbe: Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, 2002), 22.