As Kazakhstan heads for its first presidential election without long-time leader Nursultan Nazarbayev, a group of creative youth activists has shattered the appearance of stability in the country with several actions demanding that freedom of political choice be ensured and the Constitution be respected.

While support for the activists is undoubtedly strong, their actions are not unique: the modern history of Kazakhstan has seen many remarkable protests that employed art and creativity to send a message, argue political activist Galym Ageleuov and art critic Zitta Sultanbayeva.

Galym Ageleuov, historian, president of the public fund “Liberty”:

Political performance as an art and as a channel for protest is not a rare phenomenon in independent Kazakhstan. In particular, activists have responded to police and other law-enforcement agencies’ violations of individuals’ rights and freedoms with flash mobs.

To take one example, remarkable flash mobs were organized as a reaction to the murders of Zamanbek Nurkadilov, the former mayor of Almaty and Nazarbayev critic who, on November 11, 2005, was shot twice in the chest and once in the head (the government of Kazakhstan ruled his death a suicide), and Altynbek Sarsenbayev, a political opposition leader, who was shot alongside his driver, Vasily Zhuravlev, and a bodyguard, Baurzhan Baybosyn. The “alternative” activist group Society of Young Professionals of Kazakhstan (OMPK) organized theatrical actions that acted out the official government narrative of how these political killings took place. Since the official line had it that Nurkadilov, who had three shots in his body, had committed suicide, the actor who portrayed his death showed Nurkadilov shooting himself in the head and then in the heart before lying down and covering himself with a bedsheet.

The participants in those actions were Nurul Rakhimbek, Pavel Morozov, Victor Grots, and Alim Saylybayev. I also participated in these flash mobs. We were then taken to the Zhetysu district police department, where we were held for three to four hours before being released after the psychiatric hospital refused to take us. Then the police wanted to accuse us of stealing T-shirts bearing the images of Altynbek, Vasily, and Baurzhan that we ourselves had printed. But everything worked out: we were released after a representative of an important international organization supported us by turning up at the police station.

For its part, the organization Sotsopr (Socialistic resistance, a left youth association) and other young activists organized highly political actions in opposition to the regime and oligarchic rule under the title Nurotar (Nur-herd).

These flash mobs featured youth wearing sheep masks and rallying in support of the Khanate and the cult of personality in the country. The activists would fall to their knees and perform rituals in honor of our Great Leader, demanding the urgent introduction of a Khanate and an authoritarian regime. Aynur Kurmanov, Zhanna Baitelova, Andrei Grishin, Dmitry Tikhonov, and many other young people participated in the “Nurotar” actions.

In the 2000s, young people participated in a series of actions in defense of human rights activists Sergey Duvanov, and then Yevgeny Zhovtis. The participants decided to avoid detention by walking randomly around the city of Almaty with umbrellas with Duvanov’s name on them. However, despite the absence of an administrative offense, the police detained all participants. The same thing happened with the actions in defense of Yevgeny Zhovtis, in which one of the activists would go out to the Almaty Arbat (Zhibek Zholy street) every day and display a poster supporting him. For this action, I was sentenced to pay an administrative fee equal to 20 times the monthly calculation index (MCI), an index used in Kazakhstan for calculating social payments as well as fines, taxes, and other payments.

In 2007-2014, there were flash mobs held against amendments to the Constitution that would give immunity to the president’s family and legitimize authoritarian rule in the country. The first to react was Sergei Duvanov, who stood in Almaty’s Independence Square with a poster bearing a slogan in opposition to the authoritarian regime. The next day, another activist, Ekaterina Belyaeva, came out, and on the third day I went out. I remember that I made a paper crown and wrote a text about the members of parliament who vote like cowardly “rabbits” while the president leads our country to unfreedom and degradation, and I even invented a clownish dance of the mad king who hungers for power. The result was to be expected: detention, trial, and a fine of 20 MCI.

At one point, political poetry evenings at the Abay monument in Almaty were very popular. Every Saturday, people would gather and read poems about freedom. These evenings were organized by Bulat Yelemesov and Gulnara Yesirgepova.

Anti-authoritarian actions were held by the Rukh Pen Til (Spirit and Language) society led by Zhanbolat Mamai and Inga Imanbay, who organized several high-profile flash mobs with friends, primarily at the office of the Nur Otan party. They tried to pass a public verdict on the personality cult of President Nazarbayev by burning a coffin that symbolized the death of democracy in our country.

One of the first artists to master the art of political flash mobs was Kanat Ibragimov. He supported the artists who were handed down a fine from the tax services for supposedly having received income from political sponsors, coining the message “Take the last down to pants and give it to the state.”

His other actions included one titled “The fish is rotting from the head,” in which he chopped off a fish’s head with an ax, and one against Chinese purchases of Kazakhstani land titled “A Beshbarmak with Peking Duck,” in which he handed out Chinese chopsticks and offered passersby a taste of beshbarmak (a Kazakh meat dish) cooked with duck and noodles. During the 9th Eurasian Media Forum (EAMF), Ibragimov somehow got inside and undertook his “Kop soz bok soz” campaign: as a violinist played La Marseillaise, he scattered leaflets, shouting, “Kop soz—Bok soz” (“many words for nothing”).

Although some have accused the artists of being in the pocket of certain interest groups, many of them have developed and engaged in actions of their own volition.

One memorable action was that of activists Zhanna Baitelova, Yevgenia Plakhina, and art historian Valeria Ibraeva, who, wearing lace panties on their heads, took to Independence Square to protest against the Customs Union’s (later, the Eurasian Economic Union’s) ban on imports of synthetic underwear. The action can be read as a protest against the dictates of the state and its interference in the private lives of citizens. Irina Mednikova and Yevgenia Plakhina organized the campaign “For Free Internet” and also conducted flash mobs against Internet censorship, standing in line at Kazakhtelecom on Arbat in Almaty with computer mice and demanding the elimination of Internet bans in the country.

I also remember the works of Askhat Akhmedyarov, dedicated to the heroes of the land protests—Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayan — and the graffiti that our young artist Pasha Kas put on a building in Semipalatinsk as a reference to Edward Munch’s painting “The Scream.” By the way, Kyrgyz activists recently used Pasha Kas’ work in a rally against the construction of a nuclear power plant.

In 2016, Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayan were sentenced to five years in prison for ‘inciting social discord’, ‘disseminating information known to be false’, and ‘violating the procedure for holding assemblies’. They were activists of the peaceful protests against controversial amendments to Kazakhstan’s Land Code.

A Prayer / Молитва from Almas Maksut on Vimeo.

Read more on Pasha Cas: Street Art as a Public Forum in Kazakhstan: Pasha Cas

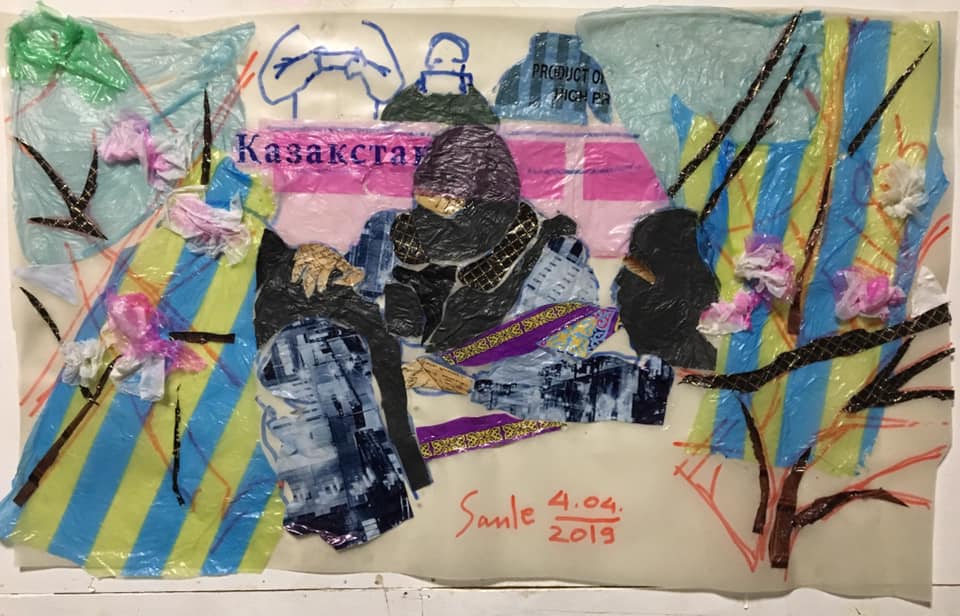

The works of Almagul Menlibayeva and Saule Suleimenova, as well as Medina Bazargaliyeva’s “Nursultan Is Not My City” action, are also quite memorable. So are the recent actions of Asiya, Beybarys, and other young artists under the slogan “You cannot escape the truth. I have a choice.” This is a worthy continuation of a fine tradition in Kazakhstan. The older and middle-aged generations should realize that their silence and neglect of civil and political rights and freedoms have fed the repressions that now affect our children and grandchildren.

Read more on Saule Suleimenova: Saule Suleimenova: A Journey to Find True Kazakhness

Zitta Sultanbayeva, artist, art critic, journalist:

Kazakhstan’s contemporary artists have developed and articulated their discourse on the theme of “art and politics” for quite a long time. They have always reacted very sharply and creatively to the political and social processes taking place in the country “here and now.” Besides the aforementioned Kanat Ibragimov, one of the brightest and most radically expressive artists, who also originates from the Kok-Serek art group, is Erbolsyn Meldibekov. In his works, such as “Pol-Pot” (1998-2000), about the nature of violence in totalitarian regimes, or “My Brother Is My Enemy” (2002), or his series of video performances, Pastan (2014), he plays on the theme of “humiliated and offended,” while his film Pinocchio refers directly to the conflict between ruler and society.

Our art duet ZITABL has made a lot of art statements on this topic. These include the anti-war performance “Miss Asia,” against the deployment of American bases in Kazakhstan and Central Asia; the installation “Just in a Cage”; and the videos “A Prisoner” and “The Blind.” All of them are metaphors for the “lack of freedom” of modern man in modern societies.

In 2017-2019, art critic Valeria Ibraeva, with the support of the Soros Foundation, organized two exhibitions devoted to human rights: “Human Rights: 20 Years Later” and “Bad Jokes.” The latter exhibition, held this spring, has displayed a number of works by contemporary artists from both the older and the new generation. One of them is a work from the series “Vintage” (2018), which became a continuation of the work “The Artist Sleeps” by Victor and Elena Vorobyev.

The coverage of the exhibition “Bad Jokes. On the 70th anniversary of the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” by the Kazakh website “Vlast” is available here.

Described herein is only a small part of what has been done by many artists and civic activists in modern Kazakhstan.