The Turkish and Turkic Collections at the British Library are the largest collections of manuscript and printed material from the Turkic World housed anywhere in the United Kingdom.

Michael Erdman

Dr. Michael Erdman is Curator, Turkish and Turkic Collections at the British Library. He was awarded the title of Doctor of Philosophy by SOAS in 2018. His doctoral research focuses on the interaction of ideology, politics, and scholarship in written historical narratives about Central Asia in both the Soviet Union and the Republic of Turkey. Prior to joining the Library in 2015, he worked as the Consul of Canada to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Yemen, and Oman, following temporary diplomatic work in Central and South America, Kuwait, and Spain.e after 1991.

What is special about the British Library’s Turkish and Turkic collections? What is the most treasured item? Does the British Museum, which also has a great Central Asian collection, cooperate with the British Library in any respect?

The Turkish and Turkic Collections at the British Library are the largest collections of manuscript and printed material from the Turkic World housed anywhere in the United Kingdom. They are particularly special because they contain an incredibly long view of textual production among Turkic peoples: from Runic fragments collected by Aurel Stein in Dunhuang; through manuscript production in the Middle East, Central Asia, and northern India in Old Turkic, Ottoman, and Chagatai; right up to contemporary publications from Turkic communities around the world. As such, they are incredibly comprehensive and attract researchers, scholars, and the interested public from both the UK and abroad.

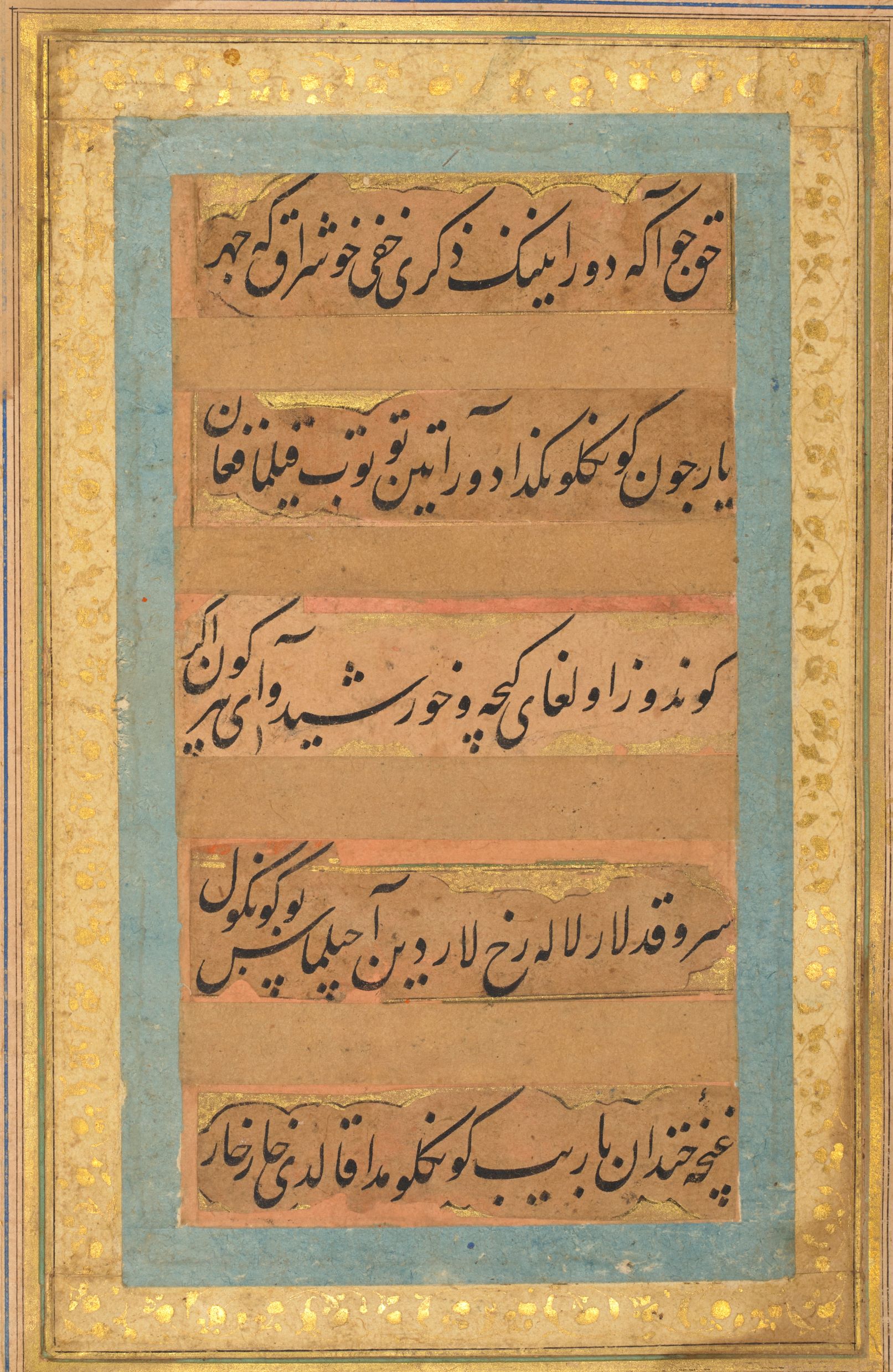

It is hard to say what the most treasured items of the collection are. To paraphrase an old saying, value is in the eye of the beholder. Among our Turkic manuscripts, we do hold some remarkable pieces. One such item is the Chingizname (Or. 3222), an illustrated 16th-century manuscript relating the history of the Shaybanids, descendants of Chingiz Khan and rulers of part of Central Asia up to the end of the 17th century. It is a beautiful work of both calligraphy and illustration, containing a scene from the life of each of the rulers whose exploits are recounted in the text.

Chingizname (Or. 3222), an illustrated 16th-century manuscript relating the history of the Shaybanids, descendants of Chingiz Khan and rulers of part of Central Asia up to the end of the 17th century

We hold numerous manuscripts of Alisher Navoi’s poetry, some illustrated, including three that date from the poet’s lifetime (1441-1501). On the more contemporary end of the scale, the British Library’s Central Asian holdings include unique publications that are often quite difficult to find in other institutions. These include a series of Kazakh historical epics about different community leaders (batyrs, biis, khans) collected from renowned aqyns at the start of the 20th century. Each of the six volumes contains a beautiful woodblock illustration, exemplifying the confluence of Central Asian traditions with the new forms and styles of artistic expression that arrived with Russian colonization. In a way, the value of the collections lies in the sheer volume of information to discover and the insights that these items can provide into the history and culture of the region.

The British Library was formally part of the British Museum until 1973, and our collections reflect the acquisition practices of the Museum—as well as of a few smaller institutions, such as the India Office Library—up to that point. When the Library and Museum split, a decision was made as to which sort of items would be retained in the Museum and which would form part of the Library’s collections. We received works that were primarily text-based, while the Museum’s collections focus much more on the plastic and visual arts. There is not a large amount of overlap, but there are occasions when specialists from one institution work with those of the other. Our goals in terms of the conservation of cultural heritage, public engagement, and education are very similar, so we often collaborate to achieve more than we could by ourselves.

How often do you get new items and what is the state of art collections from Central Asia in global museums? Is there any interest in Central Asian contemporary art?

The acquisition of new items from Central Asia is an ongoing process, especially with respect to contemporary publications. Every year, I purchase several hundred new titles from the region on a variety of different subjects: art, history, literature, politics, social reform, gender, linguistics, etc. Our aim is to reflect contemporary trends in the publishing industries and societies in which the languages we cover are spoken. I have tried to place considerable emphasis on the collection of new catalogs and art books coming out of Turkic communities, especially given some of the interesting trends that we are noticing in the region. I am very keen on reflecting the publication of catalogs of contemporary art—painting, sculpture, dance, performance, music, and others—as these can be very difficult for researchers and scholars in the United Kingdom to access without traveling to the region itself. They provide a different view of Central Asia from what is usually presented in the media, and they help to spark interest in Central Asian culture beyond the best-known manuscripts.

In addition, I have noticed that there is a rising desire to re-examine the art and design of the late Tsarist and early Soviet periods, with an eye to the particularities and peculiarities of its appearance in Turkic societies. This is something happening in the Turkic World as well as in non-Turkic countries. I try to acquire catalogs and scholarly material on some of the exhibitions and shows focused on this subject—most recently, of an exhibition of 1980s graphic design that took place in Kazan—as there is a growing interest in such topics among specialists in Soviet art history and visual culture here in the United Kingdom.

At the current moment, we are devoting more of our efforts to ensuring that our collections are properly cataloged and described, so that what we already hold can be made available to researchers and the interested public in the UK and around the world.

Do you focus on linguistic studies? How would you describe the collection of Central Asian manuscripts in the British Library from the linguistic point of view? Was Persian the language of science and poetry? And what role did Arabic play?

The various sections of the British Library’s Asian and African Studies Department are defined according to linguistic specialty. This means that I deal with works in Chagatai and Uzbek that were produced in Uzbekistan, while a colleague of mine deals with Persian items from the country, and a third member of staff looks at Arabic-language items. When these three areas are united through region- or country-based scholarship, interesting patterns and trends emerge. In particular, Arabic is especially dominant in works relating to the Qur’an, but both Persian and Chagatai feature prominently when dealing with manuscripts on popular religious practices unique to Central Asia or the lives of religious scholars from the region. Poetry was written in both Chagatai and Persian, with no clear preference for one or the other—we hold collections of poetry by many famous Central Asian poets in both languages.

What is important to stress is that the entire region was very much a multilingual one and that languages came in and out of fashion or were employed in specific contexts at specific times for specific purposes. Chagatai and Persian influenced one another in Central Asia, and it is fair to say, judging from the number of word lists and interlinear translations that feature in many of the works that we hold, that literate individuals showed interest in both languages as vehicles of literary creation and recitation.

That said, further study needs to be conducted on the language and linguistic patterns of manuscript culture in Central Asia. Our visiting Chevening Fellow from Uzbekistan, Akmal Bazarbaev, has encountered interesting trends in the way that Chagatai displaced Persian as the language of law in the region, especially during Russian colonial role in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This highlights the manner in which language is never isolated, but is used in a complex web of social, economic, and political factors all of which are important in any individual’s decision to use or not use a particular idiom at a particular time. Our manuscript holdings from Central Asia are rich in source material about these choices and await much more in-depth study by scholars and stakeholders to help paint a clearer picture about language in Central Asia before the Soviet period.

In your blog, “Silent Witnesses: Two Manuals of the Sart Language,” based on the British Library’s collection, you refer to the Sart language as another language that no longer exists. You write that Sart has become a dead language due to bureaucracy. Can you tell us about this language and how different it was from Chagatay or Turkic? And who were the Sarts? Which of the current Turkic languages does Sart resemble the most, and why is it not, say, Uzbek under another name?

The question of the Sarts is a highly politicized one, and an exact answer as to who they were and what their defining characteristics were is probably impossible for us to provide at the current time. Perhaps the best way to start is with a quote from Max Weinreich: “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” Sart as a language died out because it was not recognized as a language by the relevant state powers; the Sarts as a political group never had the chance to elevate their own dialect, under its own name, to a particular level of statecraft. Moreover, those who spoke it were encouraged to say they spoke something else, and so the Sart language died out as a category, replaced by whatever the descendants of the Sarts preferred to call their language or to speak.

“Contemporary Uzbek is the product of the last hundred years of history, and Soviet rule has had an especially important impact on its formation and development”

It is clear from the two works that I highlighted in my blog that the language of the Sarts was indeed a Turkic one, and probably would not have been too difficult for anyone who speaks contemporary Uzbek to understand. To say that it is just Uzbek under a different name, however, is a bit of historical gymnastics, and would require us to overlook the important changes over the course of the 20th century in the way that dialects and languages were treated by the State. Contemporary Uzbek is the product of the last hundred years of history, and Soviet rule has had an especially important impact on its formation and development. More than just borrowings from Russian, the Soviet period was marked by the standardization of Uzbek into a national language. This required the selection of particular traits from specific dialects, and it is thus hard to imagine that the modern-day language of the Republic of Uzbekistan is identical to any one dialect spoken at the end of the 19th century.

Beyond just language, other scholars have raised interesting questions about what sort of an identity Sart might have been. Was it an ethnic one? A national one? A social or economic one? The process of determining ethnicities and nations in the early Soviet Union was a very, very politicized one, and people within specific communities were not always able to provide their input as to what nation they felt they belonged to. As an outsider, I am not in a position to say whether Sarts were a distinct ethnic group or just a subgroup of the Uzbeks—to know that for certain, we would have to have been able to ask the Sarts themselves. What is clear, however, is that most of the people who called themselves Sarts probably merged into neighboring groups that were recognized by the Soviet state over the course of the 1920s and ’30s.

Your PhD thesis focused on the comparative analysis of Soviet and Turkish historical narratives of Central Asia between 1922 and 1937. You wrote that while they used the same resources, “Turkish accounts stressed cultural and racial unity among Turkic-speakers…[while] Soviet histories emphasized miscegenation and the historically contingent nature of nations.” Could you elaborate on this for our readers?

My doctoral thesis was based on the analysis of texts about the history of pre-Islamic Central Asia. These texts were produced in the Soviet Union and the Republic of Turkey over the course of the 1920s and ’30s and were largely geared toward state-sponsored efforts to formulate a new historical narrative, generally in support of the dominant ideology of the respective state. The USSR and Turkey were guided by very different principles, and as a result, their views of history, the nation, and race were radically different. In a nutshell, the Soviets espoused a Marxist view of history and the nation, insisting that race was an accident of geography and that nations formed only in the capitalist period, which came after three preceding stages of socio-economic development. As Stalin rose to power, this became the only acceptable thesis for writing history; other interpretations of historical, linguistic, anthropological, and archaeological sources were banned. The one twist was that the Soviet Union also declared that there was a set list of nations residing in its borders, and so historians had to work backwards, starting with contemporary nations and trying to chart out a course for them that stressed their formation in recent centuries, but on territories that were clearly defined well before the nation came into existence. History was a tautological practice, rather than one of discovery and exploration guided by scientific principles alone.

In Turkey, the state operated based on a much looser ideology than in the Soviet Union, but a general thrust can be identified. In particular, Turkey was formed as a nationalist state, and the ruling class saw the Turkish nation as top priority in the formation of state policies and viewpoints. Historians were therefore encouraged to see this nation as timeless; to indicate that it had existed for tens of thousands of years; and to contend that the people who were part of it today largely descended from the same population of Turkic-speakers that lived in Central Asia 20,000 years ago. Similar to the Soviet Union, historians worked backwards from the modern-day Republic of Turkey to the mists of prehistory. Instead of insisting that nations did not exist long into the past, however, they hunted out every bit of evidence that might support their thesis that a specific Turkish nation and race could be found in all of the ancient civilizations of Eurasia. Turkish historians also sought to use history to answer a question that was of particular importance for the new state: who is a Turk? For this reason, special efforts were made to determine the physical, linguistic, cultural, political, social, and economic traits of Turkic communities in the past and to seek these out—or seek to apply them—in the contemporary Republic of Turkey.

My analysis therefore contrasts these two bodies of writing and scholarship, aiming to understand them both within their particular contexts and in confrontation with one another. I explored how they were not formed in a vacuum, but rather contained elements that were in direct correlation—or direct opposition—to the historiographical, political, and ideological prerogatives of the opposing power. More importantly, my research seeks to provide a basis on which to understand the present by exposing and parsing the past upon which it is based: the narratives that have proven to be durable in Turkic collective consciousnesses; and the ideas and individuals who were forgotten or silenced, especially those who fell victim to Stalin’s Great Terror. I hope that the thesis helps add to the discussion in both Turkey and the former Soviet Turkic republics about what it means to belong to a particular nation or ethnic group, as well as to the understanding of how those historical narratives to which we have recourse often encode so much more than just scientific analysis of textual or material remains from the past.