While the only existing studies consider trilingualism in Kazakhstan in general, this research aims to identify possible risks and prospects for the implementation of the program of trilingualism at regional level, specifically in the East Kazakhstan Region.

Zhuldyz Moldagazinova

Zhuldyz Moldagazinova’s main research areas include sociolinguistics, ethnosociology, and world history. She is a Leading Specialist of the Center of Social Monitoring and Forecasting of the Shakarim State University, Semey. Zhuldyz holds an MA in History and Pedagogy (Barnaul, Russia) and a BA in History (Semey, Kazakhstan). Zhuldyz is currently pursuing her PhD in Sociology.

The survey was funded by the Oumirserik Kassenov grant, established by the Institutional Foundation “International Charitable Foundation—Altyn Kyran” and the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (KISI). Professor Oumirserik Kassenov (1945-1998) was a famous Kazakhstani scholar and international affairs expert. He was the first head of KISI (1993-1997). His area of expertise covered a wide range of pressing issues in the sphere of international relations, including preventing nuclear proliferation; geopolitics in Central Asia; regional, political, economic, energy, and military security; and the issues of development and nation-building in Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan’s State Language Policy

For the entire history of independent Kazakhstan, language issues have occupied an important place in state policy, becoming some of the most hotly debated questions on the national stage. Sociological research conducted by the “Alternativa” Center of Current Studies with the support of the “Open Society” Institute of Regional Studies in August 2008 revealed that 98.4 percent of Kazakhs identify the Kazakh language as their native tongue even though only 74.7 percent speak fluent Kazakh: 14.4 percent speak Kazakh but cannot write in Kazakh; 6.2 percent understand and speak Kazakh but cannot write in Kazakh; 2.9 percent understand Kazakh but cannot speak or write it; and 2 percent do not know the Kazakh language at all. To this day, there are some regions of Kazakhstan where the Kazakh language is not widely used.

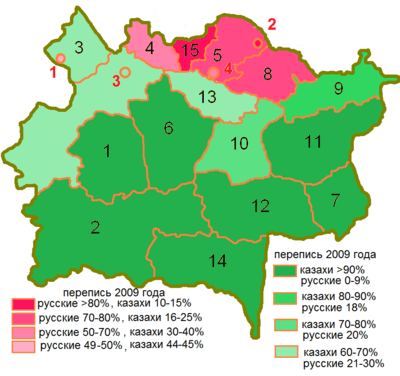

At the same time, there are regions where Kazakh predominates (chiefly in the south and the west of Kazakhstan). The ethnic composition of the different regions might explain this variation.

Given the low level of Kazakh knowledge in some regions, it is evidently necessary to strengthen the state language. However, this should be done not by displacing Russian, but by developing an adequate and accessible methodology for teaching Kazakh.

In addition to these two languages, which are officially recognized in Kazakhstan, the current policy aims to incorporate English into the linguistic environment of Kazakhstan.

Numerous draft laws on language development have been formulated in Kazakhstan. The Law on Languages, adopted on September 22, 1989, introduced the term “state language”: the Kazakh language received the status of “state language,” while the Russian language was given the status of “language for inter-ethnic communication.” Later, Article 7 of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan (1995) spelled out the status of the two languages: Kazakh was declared a state language; Russian was put on equal terms with Kazakh and was declared the official language of state bodies and local authorities.

Today, knowledge of Kazakh is a necessary precondition for getting a job in the government. A presidential decree published on June 1, 2006, stated that by 2010 all official paperwork in Kazakhstan should be done in Kazakh. The decree ruled that state authorities should “carry out a step-by-step transition of paperwork, statistics, financial and technical documentation to the state language by 2010.”

However, the Soviet legacy of linguistic and cultural Russification has helped keep the Russian language alive in Kazakhstan. The Russian language prevails in the industrial and scientific spheres. In the last decade, the English language has also come into use. Evidently, the knowledge of at least three languages—Kazakh (state language), Russian (interstate language in CIS countries), and English (international language)—has become a requirement for citizens of Kazakhstan in an increasingly global world.

In 2015, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Education and Science and its Ministry of Culture and Sport developed a Roadmap of Trilingual Education Development for 2015-2020. One of the main goals it lays out is to promote unified trilingual education within the entire education system with the help of universal standards for language learning at all levels of education. The Roadmap proposes that high schools conduct a phased transition toward teaching the natural sciences and math (IT, physics, chemistry, biology, etc.) in English; the history of Kazakhstan and geography in Kazakh; and world history in Russian.

Some public figures and politicians are concerned about the standing of Kazakh language, as they believe that trilingualism will result in the state language being overshadowed. Former president of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev believes that the Kazakh language will maintain its status after the transition to trilingualism: “During the transition to trilingualism, Kazakh will keep its dominant position.” Significant attention, he indicated, will be paid to its further development.

“Strong” and “Weak” Languages

According to the concept by Joshua Fishman, an American sociologist and linguist, language choice depends on factors such as group, situation, and topic. For instance, a bilingual Kazakh may speak only Kazakh at work, Russian and Kazakh at a store, and exclusively Russian at home. Another factor that influences language choice is the topic of a conversation. For example, in Kazakhstan, experts mostly speak in Russian when discussing technical and medical topics due to the lack of corresponding terminology in Kazakh.

Fishman’s studies provide a good lens for studying the trajectory of the Kazakh language and assessing the prospects for its future coexistence with the Russian language. Fishman’s concept divides languages into strong and weak. During the Soviet era, Russian was the “strong” (dominant) language across the USSR. In Soviet-era Kazakhstan, the Russian language practically displaced the Kazakh language from the managerial, industrial, and cultural spheres. At the time, Kazakhs were embarrassed to speak Kazakh, and most of them did not know the language at all. As a result, the use of Kazakh was minimized; at that time, the status of the language of the dominant ethnic group could be considered weak.

In independent Kazakhstan, the title of “strong language” is gradually being transferred to Kazakh; the Russian language continues to lose its dominant position in many spheres. A balanced language policy should rely not on replacing weak languages with strong ones, but on finding a balance that will allow for the coexistence of different languages.

The language shift from a bilingual state to a trilingual one is a fruitful area for research. In October 2016, therefore, the author conducted sociological research in the East Kazakhstan region, in the cities of Ust’-Kamenogorsk, Semey, and Ridder and in the village of Novobajenovo. She interviewed forty individuals aged 18-65, including 24 Kazakhs, 12 Russians, 2 Tatars, and 2 Germans. Among the respondents were 4 men and 36 women; by profession, they were university professors, school principals, businessmen, teachers, doctors, students, retirees, journalists, and lawyers. Respondents included ethnic Kazakhs who had returned to Kazakhstan from abroad (Oralmans).

The views of mothers of schoolchildren were of particular interest, as they are inherently interested in the issue of trilingual education.

East Kazakhstan

Today, nearly 1.4 million people live in the East Kazakhstan region. This region is multiethnic, with Kazakhs (60 percent) and Russians (36.5 percent) the largest ethnic groups. The Kazakh population lives mainly in the former Semipalatinsk region and the Russian population in the former East Kazakhstan region and mostly in the cities. However, the region as a whole is comparatively rural (40 percent of the population lives in rural areas) and most of the rural dwellers are ethnic Kazakhs. Alongside these dynamics, the region has also seen migration from villages to cities over the course of the past decade.

Many urban Kazakhs in the East Kazakhstan region speak Russian, which is the dominant language in the urban landscape of East Kazakhstan. This is due to the predominance of Russians in the cities of Ust’-Kamenogorsk and Ridder; these populations were drawn there by industrial opportunities.

Red shades indicate areas where Russians constitute above 50% (darker red shades – above 80%). Green shades indicate areas with Kazakh population above 60% (dark green – above 90%). Source: Census from 2009, Wikipedia

The city of Semey and the village of Novobazhenovo (located 55 km from Semey) present a slightly different picture. There, Kazakhs constitute a majority, with the result that bilingual signage in both Kazakh and Russian is very much in evidence. The difference between Semey and Ust’-Kamenogorsk or Ridder is likely due to the lack of industrial enterprises in the former, which has had the result of minimizing the use of the Russian language, as fewer ethnic Russians have ever lived there. Moreover, an influx of migrants from Abay, Aksuat, and other villages has brought the Kazakh language into the urban environment of Semey. The 2009 Kazakhstan National Population Census revealed that 61.4 percent of the population aged 15 years and older indicated having an understanding of oral Kazakh. However, even in Semey there is a group of Kazakhs who have weak command of the state language (Kazakh), most of whom are urbanites.

Migration, geography, a high proportion of Russians, industrial development, and, most importantly, the Russification policy carried out by the Soviet government are among the main factors that have strengthened the position of the Russian language in Eastern Kazakhstan. These factors were the reason why this area was selected as a pilot area for the implementation of trilingualism.

Challenges of Trilingualism

East Kazakhstan was chosen as a pilot region for the implementation of trilingual education. The present study therefore chose this region as a case study for assessing the risks and opportunities of this program.

The East Kazakhstan Department of Education developed a comprehensive plan for the development of trilingualism for 2015-2019. In the summer of 2016, language teachers were tested for their knowledge of different languages. In total, 3,400 teachers participated, including 1,200 teachers of Kazakh from schools with a non-Kazakh language of instruction, 900 teachers of Russian from Kazakh-language schools, and 1,300 teachers of English. The tests revealed that only 14.3 percent of teachers have a professional command of the chosen language: 28.6 percent of teachers of Kazakh in Russian schools, 10.6 percent of teachers of Russian in Kazakh schools, and 3.6 percent of teachers of English. After taking the test, language teachers were sent for additional training: 1,178 teachers of Kazakh from schools with a non-Kazakh language of instruction, 985 teachers of Russian as a second language, and 1,291 teachers of English.

In August 2016, the Nur-Orda school and the Kazakh-Turkish lyceum in Semey hosted professional English courses for teachers at regional gymnasiums and lyceums specializing in different subjects (physics, IT, chemistry, and biology).

According to official data from the Department of Education of Eastern Kazakhstan website, the modernization of textbooks and reference books will be the determining factor in the success or failure of trilingual education. The region has acquired uniform textbooks for studying Kazakh and English. It has also developed a standard teaching methodology for teachers of Russian in Kazakh-language schools, a unified teacher evaluation system, a criteria-based evaluation system for assessing students, and diagnostic tests for teachers and students.

Trilingual dictionaries in Kazakhstan

The study identified the risks and prospects surrounding the implementation of the program. Concerns about trilingual education included:

- Loss of knowledge in schools;

- Segregation of society;

- Further decline of the role of the state language in the life of the society;

- Work overload for students;

- Insufficient competency of teachers to teach within a trilingual system.

On the positive side, the implementation of trilingual education will put an end to an unofficial division between regions according to language preferences. All regions will use a unified curriculum on teaching in three languages and all languages will be equally used in the sociolinguistic environment of the regions of Kazakhstan.

If trilingual education manages to reach the entire population of Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan’s position on the world scene will improve, for the following reasons:

- Trilingualism is a major step toward Kazakhstan becoming one of the 30 most developed countries in the world;

- Kazakh youth will be able to study abroad freely;

- It may cause the number of foreign investors willing to invest in Kazakhstan’s manufacturing to increase;

- The number of tourists who feel “at home” in Kazakhstan will increase as the share of the Kazakhstani population that can speak English grows.

In general, the population of the East Kazakhstan region supports the transition, but they are also very much aware of the obvious obstacles to the implementation of trilingualism. These include the lack of qualified teachers; the lack of necessary material and technical resources, especially in rural areas; the lack of a unified methodology of trilingualism; and a lack of funding for training teachers. Illustrating the final point, the university lecturers who are required to teach their subjects in English are currently obliged to learn or improve their English by self-funding English classes.

It is necessary to weigh all pros and cons and study the experience of other countries with implementing similar policies. The most important requirement for the success of trilingual education is the necessity to establish an appropriate language environment. The efforts taken by schools and universities are not enough; the challenge is the lack of the language environment in day-to-day family relations. The publication of books and the broadcasting of TV programs and cartoons in three languages will allow great results to be achieved.

Linguistic differentiation between Kazakhstan’s regions is another factor that requires attention. It is necessary to assess to what extent the transition to trilingualism is possible in such Russian-speaking regions as East Kazakhstan and North Kazakhstan. In regions where the Russian-speaking population dominates, many Russians have not learned the state language. Our observations reveal that there is a category of people in East Kazakhstan who do not want to study Kazakh and do not want their children to study the history of Kazakhstan or geography in the Kazakh language. They recognize the necessity of English and place a priority on Russian, presumably due to their geographical proximity to Russia, the high percentage of the population that speaks Russian, and the lack of competitiveness of the state language. In the Kazakh-speaking regions, such as in the southern and western parts of Kazakhstan, the situation is the opposite. There, the Kazakh language dominates and is a requirement for having a full life. There is a negative attitude toward the Russian language and, more importantly, toward ethnic Kazakhs who speak in Russian.

In a sphere as sensitive as language policy, it is best not to rush to achieve certain indicators. It is more important to work competently with the state language and support the citizens in their desire to learn it.