The European Union (EU) can play a positive role in Central Asia by offering an alternative to Russia and China; helping countries build their societies and diversify their economies; and supporting regional cooperation.

Author

Jos Boonstra

Jos Boonstra is senior researcher at the Centre for European Security Studies (CESS) and coordinator of the Europe-Central Asia Monitoring (EUCAM) program.

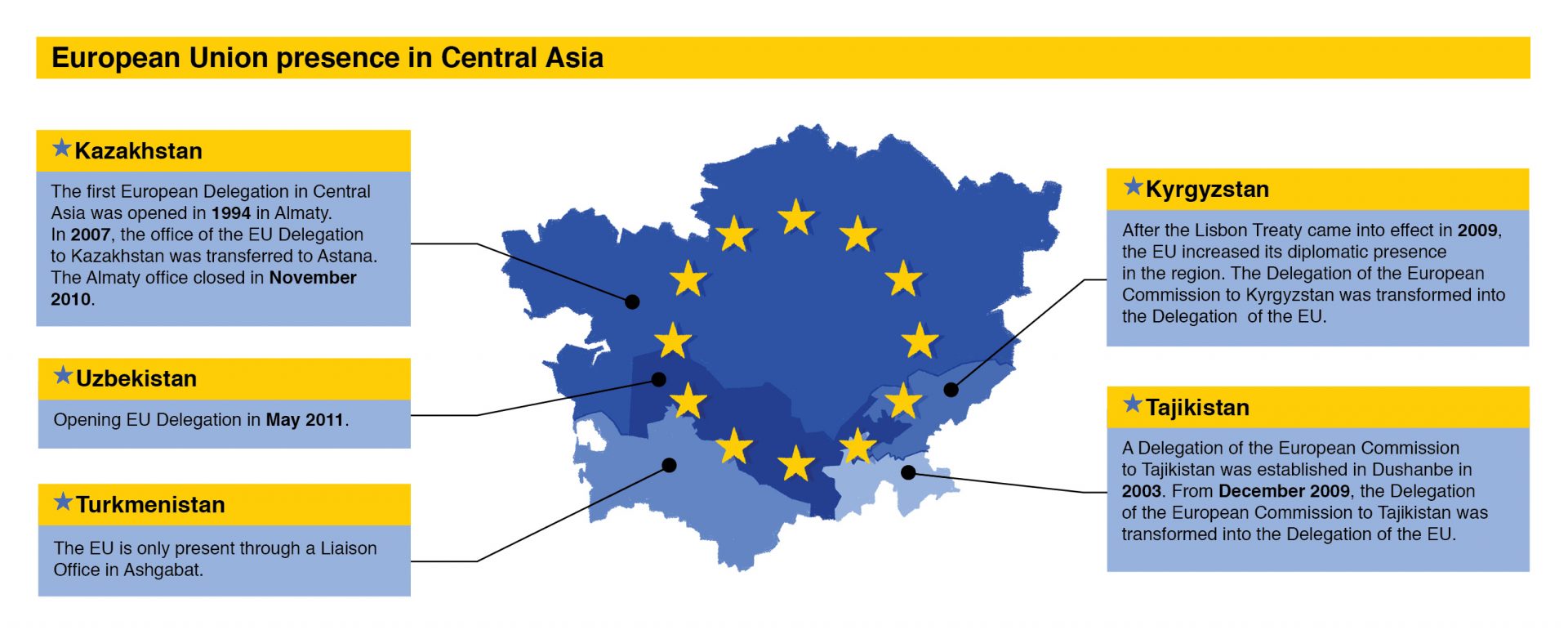

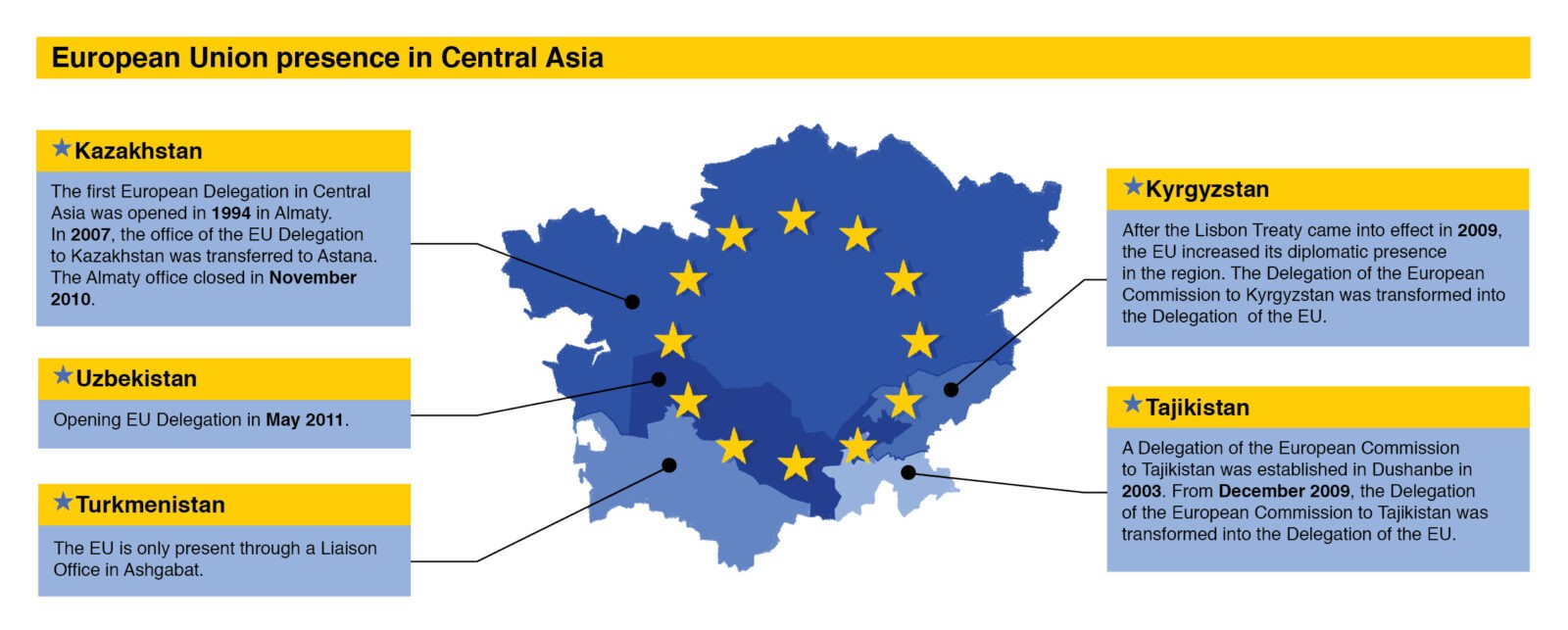

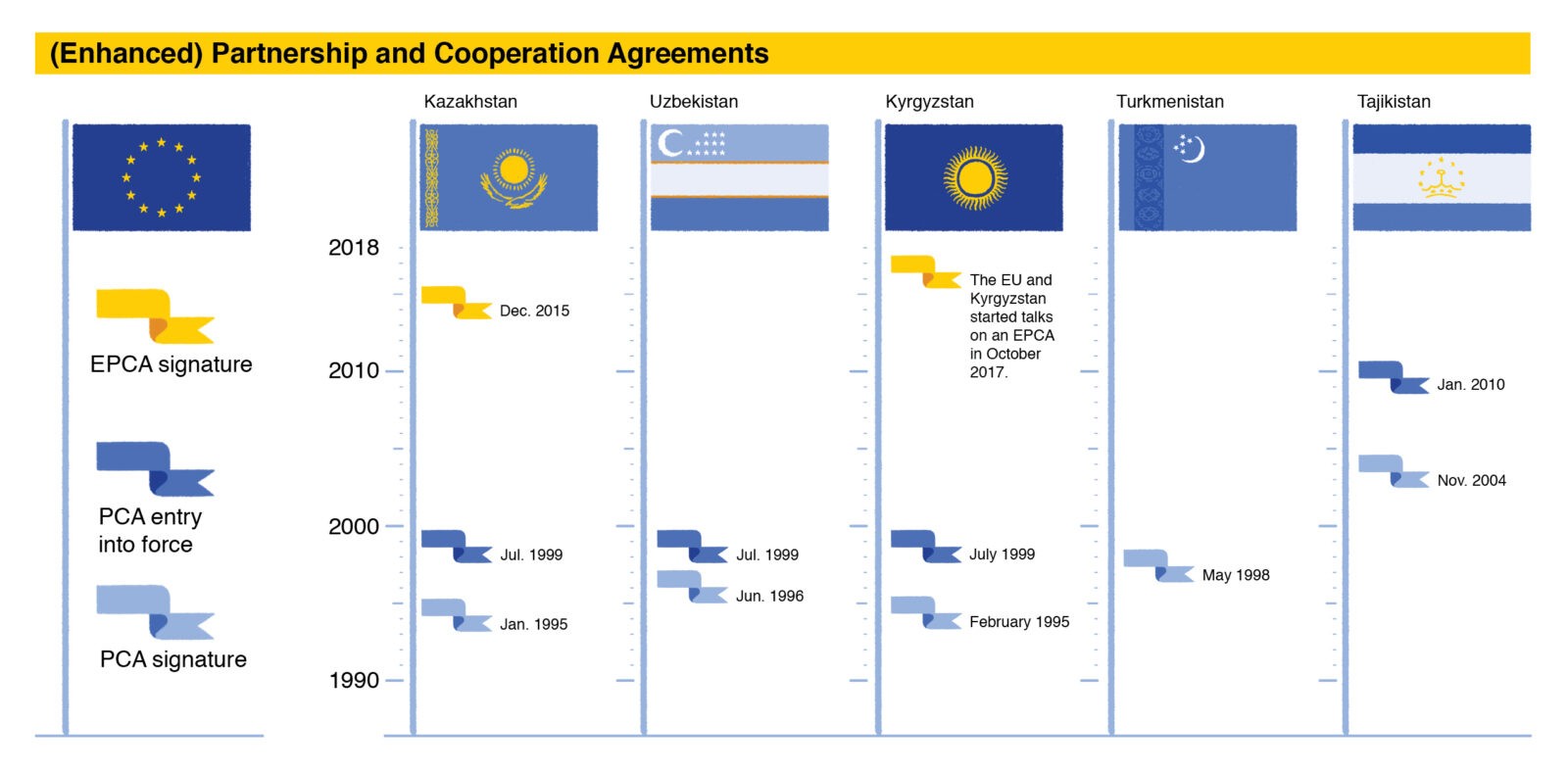

Relations between the European Union and the republics of Central Asia date back to the first years of independence of the five “stans”. But it was only after the development of an EU Strategy for Central Asia in 2007 that Central Asia appeared more clearly on the European foreign policy radar. The EU opened delegations in Central Asia, initiated projects, boosted funding, and established several formats of bilateral and regional cooperation. More recently, the EU has concluded a more extensive Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kazakhstan and begun negotiating a similar agreement with Kyrgyzstan.

Author

Riccardo Panella

Riccardo Panella is a student of International Relations at the University of Groningen and an intern at CESS-EUCAM.

The EU’s initial interest in Central Asia was based to a large degree on energy security issues. In the 2007–2010 period, the EU hoped that it could open up the Caspian and Central Asia to gas imports to Europe (via the Nabucco pipeline, for instance). Azerbaijan, Iran, and—especially—Turkmenistan would deliver gas to Europe, possibly at the expense of sales to Russia. This interest in Caspian energy projects slowly evaporated, even as China built pipelines to import gas from Turkmenistan; the 2011–2013 EU Strategy for Central Asia was instead geared toward ensuring that instability in Afghanistan as a result of NATO withdrawal did not spill over to the Central Asian states. Increasingly, debates focused on security and on linking Europe’s Central Asia and Afghanistan policies. More recently, from 2014 onwards, the EU has seen Central Asia in the light of tensions between Russia and Europe.

The region also sometimes receives negative news coverage as an exporter of radicalism, since some of the terrorist attacks perpetrated in Europe in recent years were carried out by Central Asian citizens.

Thus far, the EU’s Central Asia policy has been able to navigate international trends and crises by picking salient issues—be it energy, trade, human rights, or education—from a menu of options. Nevertheless, an updated strategy is in order. This would allow the EU to cement processes and practices that work well while cutting or transforming aspects that have underperformed. Last year, the EU decided to embark on the process of renewing the EU-Central Asia strategy by 2019. In part, this will be an internal evaluation and drafting process, but the EU encourages input by many other stakeholders, chiefly Central Asian states but also civil society organizations.

At the Europe-Central Asia Monitoring (EUCAM) initiative (www.eucentralasia.eu), we have approached research and advocacy mostly from a European point of view. Why is Central Asia important for Europe? What are our interests in this region? By starting up a fellowship program at EUCAM designed for Central Asian academics and civil society actors, we hope to increasingly take on board the views of Central Asians. Why would they be interested in Europe? Here are three broad reasons that could be regarded a starting point for such interests.

Why is Central Asia important for Europe? What are our interests in this region? Why would Central Asians be interested in Europe? Here are three broad reasons that could be regarded a starting point for such interests.

1. Europe as a Values-Driven Alternative to Russia and China

Central Asia is squashed in between two major powers: Russia and China. Its “central” location and history have made it a popular object of geopolitical strategizing. Although Chinese investment and Russian security cooperation are often welcomed in Central Asia, there is a high demand for alternatives. This makes the EU a welcome partner, for several reasons.

Firstly, the EU is seen as fairly neutral, without substantial geopolitical interest in the region. Secondly, it has become clear to Central Asian states that the EU plans to remain engaged in the region for the long haul, with a modest but steady level of investment and engagement. Thirdly, Central Asian countries are young states that seek to harness their independence and develop their identity. They want to be recognized as attractive destinations (as in the case of Kyrgyzstan) or as regional actors (an example being Kazakhstan). Informally, the EU can offer this recognition through the agreements it concludes with Central Asian states, as well as the visits of high-level Central Asian officials to Brussels and other European capitals, and vice versa.

With this European interest and engagement, however, comes a values-driven component: the EU expects Central Asian states to meet international human rights requirements and get serious about the rule of law and good governance. In a world where democratic systems are increasingly placed under stress and where traditional democracy promoters are becoming less vocal in their approach, the EU remains one of the few actors actively promoting good governance, the rule of law, and human rights (at the same time as addressing a backlash against democracy in some member states). The EU can only offer Central Asia assistance with democratization, but it is stricter when it comes to human rights. It has been able to hold regular Human Rights Dialogues (HRD) with the Central Asian states, in which both longer-term judicial reforms and concrete cases of human rights offenses have been discussed. The process needs constant nurturing to avoid becoming a box-ticking exercise; it will need to be deepened in order to have a tangible effect.

Central Asian states have often been averse to political reform, but some states have expressed interest in working with the EU on these issues. These include Kyrgyzstan, the most open country in the region; Kazakhstan, which is considering and implementing minor reforms; and Uzbekistan, which has taken a sudden interest in political and economic reforms.

2. Social and Economic Development

With the exception of Kazakhstan, Europe is not an essential destination for Central Asian exports. Nor are Central Asian states large importers of European goods or beneficiaries of large European investments (again with the exception of Kazakhstan). The table clearly shows that Kazakhstan far surpasses the other four Central Asian states combined in both its trade volume with the EU and its Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This does not mean, however, that Europe is irrelevant to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Programs like Central Asia Invest are intended to boost small businesses. More broadly economic cooperation with the EU can also help diversify the economies of the Central Asian states, which are either heavily dependent on energy exports or affected by mass labor migration.

Since the EU does not see the Central Asian region as a trade and investment priority, it is inclined to link its economic engagement to development aid programming. In that sense, the EU can be a useful partner for Central Asian countries in terms of job creation with a view to lessening labour migration or in helping to increase local cross-border trade.

But the most valuable contribution Europe can make to Central Asia’s development probably lies in the sphere of education. The EU is active on higher education through the worldwide Erasmus+ program. There is also an EU regional education initiative specific to Central Asia, and education is considered a priority sector in development cooperation with Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. The focus should not be on higher education alone, but also on elementary and vocational education. This is clearly a two-way street: Europe can have a lasting impact on Central Asia through educational reforms and programs, while Central Asian states probably have a keen interest in preparing their growing and ever-younger populations for the future.

3. Promoting Cooperation

The EU is a substantial donor to Central Asia. Most funding goes to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and regional initiatives. Even though these two countries are to a degree dependent on international development aid, its efficiency is seriously hampered by endemic corruption. Turkmenistan has received minor funding, while Kazakhstan—which is assessed as an upper-middle-income country—only receives funding through regional projects and EU global instruments. Support to Uzbekistan has been modest so far, but could see a boost in the coming years if it follows through on its recent plans for political and economic reform.

Central Asian interest in the EU’s regional initiatives has a mixed record. As the EU is itself a grand experiment in regional integration, it looks to promote regional cooperation in its foreign policy and sees the world in different coherent regions. The EU seeks to rally the Western Balkans around EU integration and has also developed extensive programming for “Eastern Partners” in its “neighbourhood”. In Central Asia, several regional initiatives have been developed to address concrete issues of mutual interest, though these projects are far more modest than those in regions closer to the EU. Central Asian states have, however, been hesitant to participate wholeheartedly in these initiatives, instead preferring to develop bilateral ties with the EU and its member states. This is exemplified by Central Asian governments’ interest in talking security with Brussels despite taking only a modest interest in the regional High-Level Security Dialogues that the EU holds every year.

But there are grounds to suspect that the EU can enhance its role as a facilitator of regional cooperation in the coming years. Uzbekistan’s strides toward better relations with its neighbors could offer an opening for such engagement, although the country has thus far initiated new cooperation only on a bilateral basis. The development of a new EU approach is an opportunity for Central Asian states to work with an experienced and relatively neutral partner to bring their countries together to address concrete subjects, ranging from water management to border management. Still, Central Asian states will want to avoid being pushed into “group therapy sessions” led by Brussels. As almost all regional cooperation initiatives in Central Asia are externally driven by Russia, China and the US, Brussels will need to carefully assess what is of interest to a group of Central Asian states and if other countries adjacent to the region (Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Mongolia) might also want to take part.

Conclusion

Central Asia does take an interest in working with Europe. The latter will need to closely listen to what Central Asians want. This goes beyond agreements with governments to include listening to civil society organizations and other voices from society. Meanwhile, Europe will also need to get its own civil society engaged in cooperation with its Central Asian counterparts.

Central Asians need to be engaged—through their governments, parliaments, academics, activists, and so on—in formulating the new EU Strategy by 2019

The interests of Europe and Central Asia may not always align, but there are grounds for considering that the two regions could develop a mutually valuable partnership. This could be based on Europe as an alternative to Russia and China; European investment in Central Asian societies; and making a realistic new attempt to bring Central Asia and the EU together in regional formats. For this to work, Central Asians need to be engaged—through their governments, parliaments, academics, activists, and so on—in formulating the new EU Strategy by 2019.

All infographics by Nicolas Journoud