Saule Suleimenova is a contemporary artist based in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

She works with a wide range of media: watercolors, wax engraving, painting on newspaper, archival photos painted over urban graffiti, scrap metal installations, and performance art.

Author

Rosa Vercoe

Rosa Vercoe is a freelance blogger who has recently started her own blog. She was born in Turkmenistan (Mary) but grew up in Kazakhstan (Almaty). Rosa is a regular supporter and contributor to the events, workshops and conferences focused on Central Asian Studies. Her educational background includes Diploma in Russian Language and Literature (Kazakhstan State University named after Al-Farabi), MA in International Relations (Nottingham Trent University, UK) and MSc in Development Studies with Special Reference to Central Asia (SOAS University of London – School of African and Oriental Studies). Rosa is based in St Albans, Hertfordshire, UK.

She has participated in numerous exhibitions in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia, as well as worldwide. Examples include “WHY SELF—Adventures of Social Identities” (Venice, 2015); “I’M KAZAKH” (Paris, 2011); ”East of Nowhere: Contemporary Art from Post-Soviet Central Asia” (Fondazione 107, Turin, Italy, 2009); “ASIA ALIVE” (solo exhibition at Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, USA, 2005); “Kazakh: Paintings by Saule Suleimenova” (Townsend Centеr, University of California–Berkeley, USA, 2005); “New Realms” (London, UK, 2004/2005); “Art of Kazakhstan” (Eurasia Gallery, Brussels, Belgium, 2004); “Exhibition within the Framework of World Citizens Assembly” (Lille, France, 2001); “Nomads” (Humay Gallery, London, UK, 1999); “EXPO-98” (Lisbon, Portugal, 1998); and “UNESCO Exhibition of Soviet Artists” (Madam Cola Collection, Paris, France, 1989/1990), among others. Her works have been sold at art auctions at Christie’s, London and Sovereign Asian Art Prize, Hong Kong. Her paintings have been chosen for inclusion in several public and private collections worldwide. She is a poet, an actress, and a public speaker. She is known for her beautiful cellophane paintings, which she skillfully uses to showcase her vision of an authentic Kazakh identity.

Saule’s work Kelin, displayed at the recent “Focus Kazakhstan: Post-Nomadic Mind” exhibition in London, has attracted much attention from the press and visitors alike. Her work was also displayed at the recent “Bread & Roses: 4 Generations of Kazakh Women Artists” exhibition at Kunstquartier Bethanie in Berlin. Both exhibitions were organized and supported by the Kazakhstan State Program Rukhani Zhangyru, as were a further two exhibitions in the USA and South Korea.

Why Saule?

My story is about Saule Suleimenova, a contemporary artist from Kazakhstan who actively pushes conventional boundaries in her tireless search for a new visual language to pursue her art activism and reflect on the past and current challenges facing Kazakhstani society. Her personal journey in establishing herself as one of the most prominent and forward-thinking modern artists in Kazakhstan mirrors to some extent the journey of contemporary Kazakhstani art in its search for recognition and its own niche in the diverse and competitive global art market. In her work, Saule likes to go off the beaten path and comes up with amazing pieces of art that make the viewer revaluate seemingly familiar things and past events.

Saule’s Childhood and Youth: Challenging Times

Saule was born in the 1970s into a very talented and intellectual family who led a comparatively cosmopolitan life for people behind the Iron Curtain. Her father was the renowned architect Timur Suleimenov. He was also the designer of the tenge, the national currency Kazakhstan adopted after gaining its independence in 1991. Her mother is an ethnomusicologist, lecturer, and leading researcher of traditional Kazakh music. In early childhood, both her parents were very busy building their professional careers, so Saule spent a lot of time with her grandmother, who used to make handmade patchwork quilts in a traditional Kazakh style. Quite often, little Saule could be seen sitting on the floor and cutting newspapers with scissors, trying to make beautiful patterns like the multicolored ones her grandmother cut from textiles. Did that play spark her genius idea to create new art out of recycled materials, I wonder?

During her school years, Saule struggled to fit the mold of a good schoolgirl. This perception of her as unconventional and flamboyant made her time at the Almaty Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering quite difficult. Her fearsome individuality was expressed even in her appearance. Shaven-headed and dressed in an epatage style, she irritated those who failed to see the artistically talented person behind her outrageous looks. She had to pay a price for those unconventional looks: she spent several nights at the police station, as the police considered her dangerous and off-the-wall. Moreover, as the daughter of a well-known architect, she was subjected to regular scrutiny and skepticism in relation to her own successes and achievements. Nevertheless, in 1996, Saule received a Degree in Design with Honors, and her final year project at the Academy received a First Class in the International Competition of Diploma Projects held in 1996 in Yekaterinburg, Russia.

In troubled December 1986, she secretly ran away from home to join the student riots in Almaty against Gennady Kolbin. Kolbin was supposed to be the new leader of Kazakhstan, an ethnic Russian planted by the Moscow central government to replace the home-grown then-leader, Dinmukhammed Kunayev. The below work is a reflection on those events which later became a turning point in asserting the right of people to express their choices and views. Saule’s desire to go back to historical milestones and the sometimes painful and tragic events of the past in search of the ultimate truth has always been the driving force behind her creativity.

At the age of 16, Saule decided to become an artist. In answer to my question as to why she made this fundamental decision then, she gave a very feminist answer. This was the age, she said, when her innocent childhood dreams and ideals were crushed by a sudden realization that, as a female, she can be seen as a purely sexual object and intimated by sleazy comments from her male fellows. Saule found that the only escape from that scenario was to immerse herself in art and drawing, which she found immensely purifying. To this day, whenever she has to deal with negative emotions or sad feelings, she uses her art as an emotional sanctuary. But for Saule, art is also a compass through which to seek answers to the social dilemmas and challenges of her time. Her teenage years saw her become closely involved with an informal network of young underground artists called “Green Triangle.”

“Green Triangle”

The “Green Triangle” period in Saule’s life was both exciting and turbulent. The network initially included students from the Alma-Ata (currently Almaty, former capital of Kazakhstan) Art College who felt that existing art canons were unable to respond to new challenges and the demands of the younger generation. In time, the group came to attract poets, travelers, philosophers, and actors. They needed a space where they could share their thoughts and experiences, one that would serve as an outlet for their energy and creativity. The “Green Triangle” movement filled that gap. It was a very fluid network, with people joining and leaving, but the core remained the same. Saule was the key person in that core, staying with “Green Triangle” until she began her studies at the Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering in 1990.

A contemporary Kazakh artist, poet, writer, and former member of “Green Triangle,” Zitta Sultanbayeva, gives a brilliant explication of the history and background of this movement in her book Art Atmosphere of Alma-Ata (2016). The members of “Green Triangle,” which was active from 1987 until 1993, performed on the streets and exhibited their works to the public practically every day, attracting a number of like-minded people. The group used to go to the Almaty mountains for days to reflect, practice shamanism, and enjoy the purity of the water, skies, and sun, drunk with the feeling of total freedom and just being themselves. Saule recalls that the group’s main motto was just three words: “Freedom, Art, Sun!”[1] In a society based on false ideals and hypocrisy, this network managed to cut through the internal contradictions and tensions. The aesthetics of socialist realism seemed to be insufficient to deal with the new social challenges, leading to a revolt among young Kazakh artists that triggered a search for alternative ideology and art. “Green Triangle” provided a sense of community and enmeshed artists in a subculture based on experimentation, freedom, and hippie-esque communal love and mutual support.

Although with time Saule drifted away from the network, becoming consumed by new interests and demands, the role of “Green Triangle” in her personal and artistic development cannot be overstated. In fact, many of her former counterparts from “Green Triangle” remain her closest friends and colleagues in the art world to this day.

Independence, the Rebirth of National Identity, and a Further Search for New Art

After graduating from the Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering in 1996, Saule pursued her interest in painting, experimenting with different techniques in search of her own identity and style. As she explained it to me in a personal conversation, this was part of the sublimation process, redirecting her inner energy to find the essence of the true beauty of art. The works she created in the late 1990s and early 2000s are about love and the beauty of everyday life and mundane things, particularly noticeable in her series ABOUT LOVE and BUSES AND BUSSTOPS. Her paintings from that period call on the viewer to pause, look around, and appreciate the beauty and poetry of every moment that life gives us. Beauty is all around us and it does not have to be glossy and glamorous, she says.

Saule experimented with painting on newspapers, wax-engraving, watercolors, and acrylic on canvas. Throughout, her burning desire was to find the right way of presenting true Kazakh-ness. She found the glorified images of Kazakh national heroes, historical figures, and languishing Kazakh girls in traditional headgear false and untruthful, seeing them as undermining the essence and dignity of true Kazakh culture and history. She considered these images an artificial, souvenir-style Kazakh symbolism supported by officials and the state-funded Union of Artists.

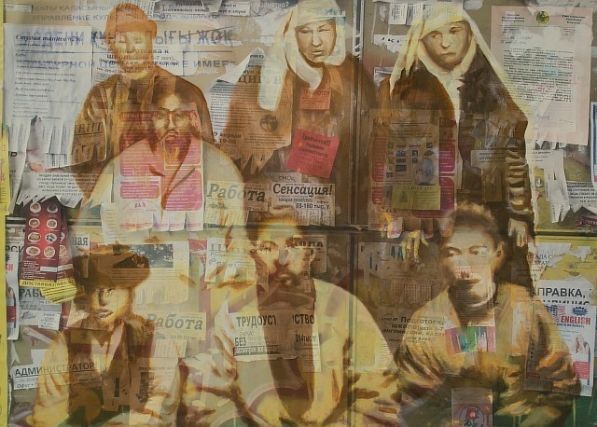

In 2004, Saule started experimenting with archival photos of the 19th-20th centuries in her series “Kazakh Chronicle.” Saule sees the “Kazakh Chronicle” as her own discovery and the first contribution to the world of Kazakhstani contemporary art, which was then in its infancy. Some young artists in Kazakhstan saw the emergence of contemporary art as the end of traditional painting. New terminology and art trends emanating from both the West and the faster-moving Russian art market led to the sense that all earlier achievements were obsolete and played out. However, Saule aspired to build on previous achievements by combining “traditional and contemporary art, painting and photography, past and present, sacred and real.”[2] In 2008, Saule came up with another new trend: layering images of archaic Kazakh people over photos of urban graffiti painted on brick walls, garage doors, and fences. These unusual double-layered compositions, made on canvas or banners, allowed her to juxtapose the past and the present, the real and the imaginary, the local and the global to show the polyphonic multi-layered nature of Kazakh national identity.

Saule concentrated on archival photos taken before the painful Soviet-era events in Kazakh history. The forced sedentarization, collectivization, and repression of the Stalin period cost millions of lives and caused mass migration of Kazakhs to neighboring countries. Meanwhile, the events of the Great Patriotic War in 1941-1945 led to the forced migration of certain ethnic groups to Kazakhstan from other areas of the USSR. The Virgin Lands Agricultural Campaign by Nikita Khrushchev in the mid-1950s and the 1960s turned Kazakhstan into a melting pot of over 100 ethnic groups, with a significant Slavic population relocated to Kazakhstan from Russia and Ukraine. As a result, the Kazakhs appeared to be a minority in their own country, which affected the position of the Kazakh language and memory of national history and identity. It was therefore very important to Saule to go back before these painful events to find the truth about the Kazakhs, which for her lies in the nomadic shamanic period of Kazakh history. As she said in one of her interviews, finding the right balance in portraying the national identity is important not only for external image-making, but also—and even primarily—for Kazakhs themselves.

Saule sees art as the messenger of her personal understanding of national memory. She does not intend to show archaic images of Kazakhs as victims, as they are normally portrayed in the postcolonial discourse, but rather as truthful, immensely beautiful, and proud people full of natural grace and dignity regardless of their status and nobility level. It must be mentioned, however, that not everyone admired these images when Saule started experimenting with photographic images of the archaic Kazakhs. Initially, she was heavily criticized for depicting the Kazakhs as backward. She really had to fight to defend her vision that beauty must be sought in truthful, authentic images of real people.

These works reflect on a tragic event in Kazakh history, when over 1.5 million Kazakhs died of starvation and hundreds of thousands more had to flee their lands to save their own and their families’ lives.

In 2014, in her continuous search for new forms of visual expression, Saule came up with the totally new concept of cellophane painting. Not surprisingly, this genius discovery had a very humble beginning.

Saule’s Cellophane Painting

In my personal conversation with Saule, she told me the story of that magic Eureka! moment. One day, she opened her kitchen drawer, and there it was: a big pile of multicolored plastic bags falling out of her drawer. Saule found herself fascinated with the abundance, variety, and richness of colors locked in the simple plastic bags. Why should I buy new paints and continue the vicious cycle of human production of waste when I can actually recycle these plastic bags for my art?, she thought. She posted on Facebook asking her friends to pass along any used unwanted plastic bags—and she received a big pile! That was the start of a series of amazing cellophane paintings: Three Brides; Kelin (Daughter-in-Law); Youth Riot Zheltoksan December 1986; Asharshylyk/ Famine, 1932: The Exodus of the Kazakh People during the Famine; Asharshylyk/Famine, 1932: Survived Children; and many others.

Saule invented her own original technique using a gun with hot silicone (an ordinary glue does not stick the pieces of plastic bags together). The hot silicone melts the plastic material, with incredible results: the transformation of a puzzle of separate bits and pieces into a fascinating work of art. Saule explains the use of plastic bags by saying that “multiple layers of meanings, cultures, visual images, plastic bags help me to find the way to my ‘Kazakh-ness’ and finally to myself.”

Future

Saule has brought diversity to her cellophane painting by adding trash bags as a new reproductive medium. At the recent “Focus Kazakhstan: Bread & Roses” exhibition in Berlin, she presented her paintings made out of German trash bags. The idea came from the German film “Winds of Desire” (in German: ‘Sky above Berlin’), directed by the famous German filmmaker Wim Wenders, during her three-month art residency in Berlin hosted by The Momentum Worldwide—The Global Platform for Time-Based Art: Film Video, New Media, Performance and Sound. Saule found this experience immensely enriching and satisfying. She will no doubt come up with fascinating new projects, styles, and forms of media soon. Just wait and see!

Acknowledgements: The author would like to express her gratitude to Saule Suleimenova for the valuable information and images of her works.

[1] Z. Sultanbayeva/A. Nurieva, Art Atmosphere of Alma-Ata (Almaty: TOO ‘Service Press’, 2016), 147.

[2] Ibid., 340.