A short transcript of the lecture by Dr. Marlene Laruelle Kazakhstan’s Nationhood: Politics and Society on the Move at the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies (CERES), Georgetown University (February 08, 2018).

Full audio below

One may wonder when Central Asia will stop being labeled “post-Soviet.” When do we exit “post-Sovietness”? In this paper, I argue that Kazakhstan is on its way to entering a new era, that of post-post-Sovietness, and that this new era also entails moving from Kazakhstan-ness to Kazakhness. We tend to see the Central Asian region through the lens of its regimes, and we therefore stress its stability—even, sometimes, its immobility. But society is on the move in Kazakhstan, and politics is following in its footsteps, though more slowly.

Author

Marlene Laruelle

Associate Director and Research Professor at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University.

Marlene Laruelle works on Russia and Central Asia and explores post-Soviet political, social and cultural changes through the prism of nationhood and nationalism. She has been the Principal Investigator of several grants on Russian nationalism and political elites, on Russia’s strategies in the Arctic, and on Central Asia’s domestic and foreign policies.

There has been a good amount of research done on Kazakhstani nationhood, but the majority of these works were completed in the 1990s or about the 1990s. We missed many evolutions in the 2000s: demographic changes and their outcomes, rural migration to cities, and the birth of a Kazakh-speaking urban world, as well as growing regional differentiation. We also missed the cultural transformation that these evolutions brought with them—for instance, we do not have any good study of the Kazakh-speaking media world, despite the fact that it is a becoming a very active and specific forum for discussion.

There are three key elements that indicate Kazakhstan’s transition from the post-Soviet era to the post-post-Soviet era: demography, Islam, and culture/language.

Demography

Across the northern oblasts of Kazakhstan, the number of Russians is on the decline. They now represent between 36 and 50% of the population of each of these regions, making them a minority in every oblast. This is a dramatic change for the country since the 1990s.

The largest immigration flows from Kazakhstan to Russia occurred in the early 1990s, but these departures continue at a reduced rate. Russians emigrate by themselves or through the Compatriot program launched by Russia in 2006. Among new citizens of the Russian Federation, the largest number come from Kazakhstan (a distinction the country has shared with Ukraine since the Donbas conflict). Often, this emigration takes place over two generations: children leave to study in Russia, then find a job there, and their parents join them when it is time for them to retire.

Another important element is the demographic trajectory of Russians in Kazakhstan. The average age of a member of the Russian minority is 44. The average age of an ethnic Kazakh, by contrast, is around 23. This is a huge demographic difference that means that in 10 to 20 years, the majority of Russians living in Kazakhstan will be retired people.

Also of note is the massive urbanization of ethnic Kazakhs. The number of Kazakhs living in cities has quintupled since the 1970s, growing from one million to five million. As a result, half of ethnic Kazakhs are now urban. Kazakhstan’s urban identity has been dramatically reshaped by these mass departures and mass arrivals.

Yet even if the differentiation between the Slavic north and the Kazakh (and partly Uzbek) south is diminishing, the regional gap remains critical in many other respects. Southern oblasts are the most dynamic demographically, as they have a higher fertility rate. The south is also where the majority of the rural population lives. Moreover, ethnic repatriates (Oralmans), who now constitute 10% of the ethnic Kazakh population (one million people), live primarily in these Southern oblasts, and their integration remains challenging.

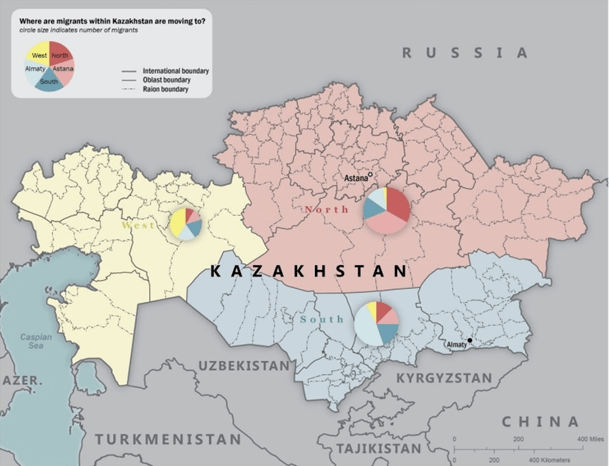

Like everywhere in Central Asia, internal migration from rural areas to cities is a massive post-Soviet trend. Yet in Kazakhstan, internal migration remains mostly regional: people travel within their region, but not really to another region—with the obvious exceptions of the two capital cities, Astana and Almaty. The state’s programs to boost South-to-North migration have largely failed.

As a result, Kazakhstan is demographically, economically, and (to some degree) culturally divided into three regions, each of which has a strong and separate identity.

Two conclusions can be drawn from these demographic changes:

1) The “Russian question” is slowly disappearing, and will probably not be politically salient going forward. Many Western experts who worried about a “domino scenario” following the annexation of Crimea not only missed the specificity of the Pontic region in Russia’s perceptions, but also based their analysis of Kazakhstan on knowledge from the 1990s, which is no longer relevant.

2) The new demographic and sociological trends shaping Kazakhstan today are the structuring of a Kazakh-speaking urban world and a growing differentiation between three regions (North, South, and West) with diverging patterns.

Islam

The role of Islam, both in individual and public life, is changing rapidly, in line with what is occurring across Central Asia. The shift is particularly significant in Kazakhstan because it is the Central Asian country where Islam has historically been the least visible. Thanks to research by Barbara and Azamat Junisbai, we know that almost all ethnic Kazakhs (95%) now identify as Muslim. This does not mean that they practice Islam so much as that they feel they have to identify with Islam as the national religion. Among the 5% who do not, many probably identify as Christian. It is becoming increasingly difficult to say that one is atheist or agnostic.

We also see a growing number of people with religious beliefs (in an afterlife, for example) and who practice some aspects of Islam (mostly zakat and Ramadan; praying remains a minority behavior). Another important element is the birth of a so-called “bourgeois” Islam, i.e. an Islam practiced and exhibited by the urban middle classes, accompanied by new urban codes such as halal cafés, Islamic fashion, and the rise of new Islamic business ethics. In sum, Islam is progressively becoming a new code promoting individual morality and a more normative public space.

Culture and language

In this area, changes have become increasingly remarkable since the beginning of the 2010s. As I noted previously, the Kazakh-language information world is growing and is largely dissociated from the Russian-language one. In a sense, it is like having two countries in one: the two information spaces function in relatively close proximity without interacting with one another.

Kazakh-language information world is growing and is largely dissociated from the Russian-language one

Studying in Kazakh is now the dominant trend. About two-thirds of pupils are now enrolled in Kazakh-language schools. This means that, statistically, almost all Kazakhs are now instructed in Kazakh. Of course, some pupils—especially among the elite—continue to be instructed in Russian, or in English in Western-oriented schools. University is also becoming Kazakhified, with about 50% of students following Kazakh-speaking curricula.

This progressive de-Russification is the product of demographic evolution. The majority of voluntarist programs launched by the Kazakh authorities to promote Kazakh language over Russian had limited success, but Kazakhification is now happening naturally with the arrival of new generations and the urbanization of Kazakhs. The authorities have also developed another way to accelerate de-Russification: the promotion of English as a mandatory third language in the education system. The success of the project remains to be seen.

The Kazakh-speaking media world has already been shaped by a nationalist mindset. This trend is now becoming a dominant one, especially on social media. Several tens of nationalist-minded bloggers have about 20,000-30,000 followers each. This may not seem like a large following, but they are mainstream for their small niche: the younger population using Kazakh-language social media.

Another fascinating drift to follow is the rise of memory debates. The Kazakh-speaking intellectual world has always been focused on issues of national identity, relationship to Russia (and China), Russian colonization and Soviet-era famines and repression. These debates are now transcending their small niches to occupy more visibly the public domain. The centenary of the 1916 revolt in 2016 was a good example of the tensions between the official narrative and all those pushing for a critical reading of the interaction between the steppic world and Russia. The centenary of the 1917 revolutions in 2017 highlighted similar issues. And in the next two decades, Kazakhstan will have to commemorate the first two decades of Soviet history, a very turbulent period. The country is set to discuss Alash-Orda, the birth of the Kazakh ASSR, national-communism, famine, Stalinist repressions, and so on. Historical politics will therefore become a key element of the national debate in the forthcoming years.

What is the political impact of these changes?

One may wonder whether all these demographic and cultural changes impact politics. I think they do. Thanks to sociological polls and surveys, we know that the younger generation thinks differently from older generations: young people support everything related to the market economy and have a greater belief in the notion of individual success. But youth is not more pro-Western than other age cohorts. On the contrary, young people are significantly less likely to support democracy that previous generations. A large majority do not consider the West to be a model of development that Kazakhstan should follow, instead calling for the country to elaborate its own path based on its cultural values—whatever the content of these so-called Kazakh values may be.

From what I have said, it is evident that everything Kazakhstani is on the decline and everything Kazakh is on the rise. This is a critical element of the shift from the post-Soviet era to the post-post-Soviet era.

Everything Kazakhstani is on the decline and everything Kazakh is on the rise

The state is progressively recognizing all the changes I have discussed. I see two important symbolic steps in this recognition. The first is the decision to shift to the Latin alphabet in 2025. The second is the state program about “modernizing public consciousness,” launched in 2017—a very Soviet-style formulation, but one that says a lot about how Ak-Orda is trying to deal with the ongoing changes in the country. The state, too, is in the process of changing. Young nationalists are now well-represented in some state institutions, especially in the media sector. There is a new generation of akims in their 40s who are being promoted. Step by step, the public administration will be nurtured and innervated by this new cultural atmosphere.

All this exemplifies how President Nazarbayev is preparing his legacy: accommodating this new mindset without letting it become too confrontational and oppositional, while at the same time pointing out the way to the new, post-post-Soviet era. It is interesting to see changes happening while Nazarbayev is still in power, without having to wait for the presidential transition, as was the case in neighboring countries. The Kazakhstani authorities have been showing less ideological creativity than their Russian counterparts, but they are catching up, becoming more adaptive and receptive to bottom-up dynamics.

To conclude, one may wonder what all these changes mean for the relationship with Russia. For Moscow, losing support in Kazakhstan could have dramatic consequences: it would close direct access to Central Asia and delegitimize Russia as the leader of regional integration. The new Kazakh generations want to be culturally more distant from Russia, yet this does not mean they have a negative perception of the country ( with the exception of those who take clear ethnonationalist and “post-colonial” stances). The majority do not want too much cultural submission to Russia, yet nor do they reject it; the prospect of China’s cultural hegemony raises much deeper identity concerns. Economically, Kazakhstan is well balanced between the European Union, China and Russia—Moscow is an important actor in the country’s economy, but only one among several. It is at the strategic level that Kazakhstan remains heavily dependent on Russia, almost unable to secure its own sovereignty without Russia’s support. Indeed, Russia still controls several military polygons on Kazakhstan’s territory.

Yet we have to remember that, as Kazakhstan is changing fast and exiting the post-Soviet framework that has dominated for a quarter of a century, Russia is also undergoing deep changes. The future of both countries and their interaction therefore remains open and adaptive to the new contexts taking shape before our eyes.

Full audio:

Illustration by Erden Zikibay