Looking at state-society relations in Central Asia, Diana Kudaibergenova sees contemporary art as an alternative forum for discussions and critique. Dr. Kudaibergenova has published extensively on this topic, focusing on such issues as the search for national identity through art, imagined geography, and alternative views on gender and power expressed through Central Asian art. In this interview, she discusses some of the “brave attempts” that artists in Central Asia today are making to problematize these issues and conceptualize debates about power and representation.

Diana T. Kudaibergenova

Lund University/Cambridge University

Dr. Diana T. Kudaibergenova is a political and cultural sociologist working on social theory of power, nationalism, law, and elites in a comparative and historical perspective.

Her first book, Rewriting the Nation in Modern Kazakh literature (Lexington, 2017) deals with the study of nationalism, modernisation and cultural development in modern Kazakhstan and her forthcoming book focuses on the rise of nationalising regimes in post-Soviet space after 1991. Currently she is completing her third book manuscript on power, state and resistance in contemporary art of the post-Soviet sphere.

Her articles appeared in Nationalities Papers, Central Asian Affairs, European Journal of Cultural Studies and Journal of Eurasian Studies. Kudaibergenova’s overall approach to the study of power is also reflected in her current 2-year long project on Crimea.

What does contemporary art look like in Central Asia today? What are its commonalities and striking differences (no doubt there are a range of artistic expression, techniques, themes, and forms of financial support)?

Contemporary art in Central Asia is a reflection of the problems each society is facing and an attempt to engage in dialogue about these issues. Who are we? Where are we going? Is the transition over? How shall we protect the rights of our people? All of these questions find answers in the works of local contemporary artists. For many artists, “contemporary art” means the liberation from state control and funding that occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but also liberation from censorship and totalitarian frameworks of production. In contemporary art, there are diverse forms, expressions, and themes, and each artist seeks to find the focus of their own work. Some challenge conservative gender perceptions and models, while others explore the archives in search of something “authentic,” real, non-Soviet.

For many artists, “contemporary art” means the liberation from state control and funding that occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but also liberation from censorship and totalitarian frameworks of production

Saule Suleimenova, for example, was the first to explore the 19th-century archival photos of local people in Central Asia. She reflected on her own identity search by putting their faces, attire, and figures against a background of the very contemporary urban structures that surround her on a daily basis. These works create layers and complex dimensions of the past, present, and future as a time framework, but also represent layers of memory, history, and lived experience in the place called contemporary Kazakhstan.

All of a sudden, these archival “ancestors” were looking up from urban walls, rusty garages, or bus stops. You could try and see the “true” image of the country or the nation by staring into the depth of these layers. To me, Suleimenova’s works are very philosophical because they reflect the ongoing obsession with—and search for—the “authentic” national idea in Kazakhstan. Finding this mystical idea of the nation is politicians’ main goal. In other words, while some actors continue to talk about “searching” for the nation or national idea, they tend to forget that they do not own this task and that perhaps it is, in itself, a useless exercise. It never goes beyond declaration because that is all it is there for. Saule Suleimenova feels this problem on a deeper level—all these promises empty of meaning—and she critically searches for the answers to her own questions: What is my identity? Is it necessary to have one? Who are we and where are we going? And perhaps these are more useful questions than the constant and growing perplexity around the concepts of “authenticity,” the “national idea,” the “eternal nation,” and so on. Artistic critique is complex here: it questions what is conceptual about the “national idea” in the post-independence period.

Other artists also explore the issue of identity. It is a very popular theme, and contemporary art opens up a lot of space for debating these questions.

There are very strong artistic discussions about power and representation. A key question for many artists is, “Who has the right to represent?,” and I salute their brave attempts to problematize it and conceptualize it.

One thing that I stress in my works is that in Central Asia, the contemporary artist has a strong voice and is a powerful actor in social and cultural discussions. Some discuss the power of traditions; others comment on gender roles in families, the economy, or politics. And these debates and reflections find audiences much quicker than do monotonous slogans or long wordy programs. That is another important commonality for Central Asian artists: they find an audience and support.

In Central Asia, there are no strong local markets for contemporary art, nor state institutionalization of it. Thus, contemporary art is neither elite nor inaccessible; on the contrary, it is public and open to starting a discussion with large audiences. Most contemporary art galleries have free admission, and tickets to state museums, where contemporary art is sometimes exhibited, are not too expensive (less than US$2 in Astana, for example). There is also a growing interest in combining creative spaces with other activities—public lectures, free discussions, interactive lectures, film screenings, and even activities for kids—in order to encourage more participation.

Contemporary artists themselves strive to engage with their audiences. There are multiple groups and networks on social media, and artists encourage people to participate in discussions, to dialogue with them. We are seeing a great boom in contemporary art development across the region, not just in big cities or well-connected circles.

There are fantastic artists in Bukhara, Tashkent, Almaty, Shymkent, Karaganda, Astana, Dushanbe, and Bishkek, but also in Ashgabat and Turkmenabat, among numerous other places.

What networks have emerged? And how are they maintained?

Because artists are incredibly open to discussions, there are a lot of networks and groups. In the field of contemporary art, most actors know each other well or at least know the context in which one another are working. When new names emerge and their works appear at group exhibits, the community tries to get to know them better and spread the word about them. I have come across this phenomenon quite a lot during my interviews and discussions with artists. Sometimes certain artists message me saying, “Did you see this new artist? Did you see how exciting his or her work is?” If I schedule an interview with an artist, that artist may tell me, “You should also speak to this new emerging artist, who is very talented.” So even outsiders benefit greatly from this inter-connectedness within contemporary art—“tusovka,” as some artists call it.

There are also different groups within the larger network of those who identify themselves as belonging to the “Central Asian contemporary art field.” Interestingly, these groups are not formed based on citizenship or country of residence but rather are oriented around common interests, sympathies and shared values, genres, or forms. I have often witnessed artists from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia, Turkmenistan, France, Italy, and elsewhere quickly find a common language of art while at a party in the mountains, in someone’s studio, in an exhibit hall, in an independent gallery, or on the road. Locations, passports, languages, and dialects do not matter to this network of people. Artists across the region have long since erased borders and divisions, the internet is connecting people from near and far with rapid communication, and most importantly, artistic production is the adhesive that holds this great community together and keeps it so strong.

Can we say that contemporary art has evolved beyond social realism, perestroika, and independence to a new (millennial) stage?

Yes, absolutely. Art is connected to the society from which it emerges and operates. Hence, since both go through periods of development and transformation, art and society continuously influence each other. But we as researchers tend to focus more on the transformations at social, political, and economic level, and only then on cultural development.

The question of what changes in art over time and why is a very important one. In my work on contemporary art in Central Asia, I start the discussion in the mid-1980s, with the advent of perestroika and structural changes in Central Asian societies from 1986. This is the period when the majority of my current respondents went through different stages of what they call “cultural awakening,” understanding that Soviet propaganda was false, what the state was telling people was not true, and that they had been living a lie this whole time. (I write about this in my paper “Punk Shamanism, Revolt and Break Up of Traditional Linkage: The Waves of Cultural Production in Postsocialist Kazakhstan,” published in the European Journal of Cultural Studies.) During this period, a lot of underground movements emerged in different parts of Central Asia and across the Soviet Union. Most of these movements were formed by non-conformist young people who sought alternative truth, alternative aesthetic, alternative identity.

It was not the first time in history that underground or dissenting movements emerged in the region and it was definitely not the first time that alternative art forms and experiments emerged. Yet I found in my research that it was a crucial moment for the emergence of “contemporary art” as a completely new conceptual tool, reflecting “now-ness” and openly revolting against the dominant form of doing art. When these groups of artists started revolting against the socialist realist canon in different parts of Central Asia, they inevitably also revolted against the political order of how things ought to be done—and consequently, they revolted against their own position and identity as Soviet citizens. This was both a collective experience of being part of that movement but also a very individual and private transformation into a new type of an artist, one that each of my respondents remembers differently. Many found themselves lost and searching for the meaning of who they were far from their homes; others returned to traditional crafts and materials to seek the knowledge they had forgotten and thus reverse their cultural amnesia.

All of these encounters were intense practices that were then shared and discussed with the public, both locally and abroad. A lot of these practices and works were conceptualized by the artists themselves, as well as by curators and art critics. Yet not much of it has remained in print, been kept in public libraries, or been published widely; the first wave of contemporary art in the region is still kept in private libraries and oral histories, which I am currently trying to collect and combine.

I remember how, during an interview with one artist in Almaty, he mentioned one of the first contemporary art exhibitions he saw in Moscow in 1990. He described the event, told me the address of the gallery, and discussed some of the works that had a great impact on him. His memory of these feelings was clear to see during the interview, but I lacked any further information about the exhibition until I accidentally found one of the few remaining catalogs from that Moscow exhibition while searching through the Cambridge University Library collection in the West Room. It’s a long story, but we are not allowed to borrow books from that collection, so you have to spend time in the room with all the rare books. I was astonished when I found the same address and date and noted the works that had had such a great impact on the artist to whom I had spoken. Or sometimes during an interview someone tells me, “Go look through our home library,” and I accidentally find exactly the catalog, photo, or book I need. It always feels like collecting missing pieces of the puzzle.

There are a number of exceptionally good works on contemporary art in Central Asia to date. Among them is the work by artpologist and anthropologist Zhanara Nauryzbayeva that inspired a lot of my own research questions. There are articles by local curators and educators, for example Yulia Sorokina, and also a 2011 book of articles written by Valeria Ibrayeva.

But in my view, there are still many pieces of this puzzle that we need to research, note down, and analyze.

I would not say that the search for post-post-Soviet is over yet. My observations and interviews with artists demonstrate that while new generations of contemporary artists are emerging, a lot of them are still interested in similar issues of searching for the Self. As I said, art and society are deeply interconnected and reflect one another; if a society finds itself still facing the same problems as in the late 1980s, or if certain issues were exacerbated by the transition period in the 1990s, these problems will be reflected by contemporary artists. The key theme here is Time itself and how we respond to time—how do we view and understand the past, our history, traditions? One of my favorite themes is how new state-sponsored “official” artists try to conceptualize the past by making it very contemporary. What I mean by this is that they focus on depicting the nineteenth century in the brightest shades of colors, which only became available ten years ago, or they imagine great ancestors in textiles and fabrics so modern that the line between past and present is completely blurred. Our imagination of the past is inevitably limited to what we know about it in the present and to what we can operate with nowadays.

One of my favorite themes is how new state-sponsored “official” artists try to conceptualize the past by making it very contemporary

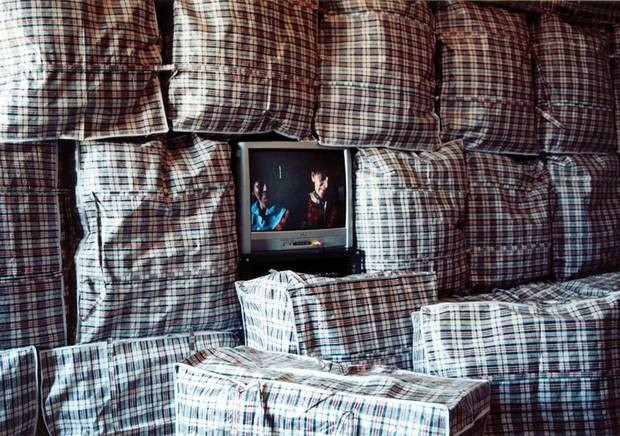

Of course, one can try to create works with the materials available to nineteenth-century craftsmen—one can even try to conceptualize it beyond a simple souvenirization (a concept used by Almagul Menlibayeva) or imitation—but that will not make it more “ancient”; it will still be made in the present. All the contemporary artists I have interviewed are completely aware of this constant replication and limitation, so when they gaze into the yurt, it is the twenty-first century yurt of a globalized nomad who wears clothes made of Uzbek cotton but sown in China and sold in Dordoi bazar in Bishkek or brought to a local barakholka bazar in a nearby city. To contemporary artists, there is nothing wrong with focusing on the now-ness and contemporaneity of people who play the “ancient” game kokpar dressed in fake D&G sports suits (see Said Atabekov’s “We are from Shymkent” series) or flying a drone with adyraspan grass in an ancient ritual of protecting the main building of the Astana Expo from the evil eye (see Anvar Musrepov’s video art). But for many official artists who are sponsored by goszakaz (the new form of socialist realism and state propaganda), the objectification of the past and present is more important than its problematization. They are guided by the need to provide the only true picture of what happened before colonization, from how nomadic rulers looked to how horses were proportioned.

I do not mean to say that any of these things are good or bad, right or wrong, and believe me, I am one of the biggest fans of monuments including horses—I study them in great detail in every town and city I go to and I have quite a collection of horse photos.

I am no art critic to judge these practices; on the contrary, I am a cultural sociologist seeking to become part of them in order to better understand how they emerge and why. What fascinates me is this obsession with authenticity and time, this compulsion to make everything look and talk like it would have in the nineteenth or eighteenth century, and how all of that can be combined with new technology, urban developments, and globalization. I recently saw and was fascinated by an old Central Asian carpet that depicted Alexander Pushkin. The carpet was done in an old technique and was exhibited in a nineteenth-century medrese-turned-museum to help demonstrate the continuity of local traditions through time. To me, this is also a perfect example of contemporary art, even though it is probably not positioned as such. The carpet was probably made in the 1950s and exhibited in its current form and current place only twenty or thirty years ago. It is contemporary because it reflects on the complex layers of the current societal situation.

At this point, I personally see a great variety of different flows, movements, perceptions and schools of thought in art of Central Asia: some are still stuck in socialist realism, others have mutated into later forms, still others are completely unexpected and probably even unaware of how contemporary and conceptual they are. And of course there is a swathe of clearly positioned contemporary and independent (from the state) art that explores all sorts of directions. In my own analysis and forthcoming book, I identify time, identity, state, and self as four major themes—rather than stages—of contemporary art in this region at present.

Which artists would you like to single out and why?

I recognize all contemporary artists for their bravery and talent. They have what it takes to stand up and express their voice—their viewpoint—despite all sorts of fears, self-doubt, and a lack of funding. They also have enough strength to have continued doing so throughout all these years of post-independence. They pose questions that not many other people pose openly and they offer a platform for discussion that everyone can participate in. In the absence of contemporary art museums or lacking permission to exhibit in state museums, they do not give up, instead turning their homes into meeting points and using open-air spaces like botanical gardens, parks, public squares, and boulevards for open public exhibitions. Through these actions, they change the whole paradigm of how people think—they inspire so many people.

What I have understood throughout my long-term fieldwork and interviews with artists in the region is that they are the true civil society—they create this space for pluralism, critical thought, and open discussions and it really matters.

Although some people might be tempted to create lists of the most radical, important, talented, critical, or successful artists, I feel that this creates unnecessary hierarchy. In my opinion, you can find incredible talent and critical conceptualization in the works of any contemporary artist and they all deserve to be recognized, to be heard of, and to be celebrated. I really hope the world will hear more names and see excellent contemporary artworks emerging from this region soon and that all artists will be represented more widely.

How do they relate to societal needs—to politics? Why do many focus on environmental issues? Is it a comparatively safer issue through which for them to express anger or other emotions?

The artists I interview agree that if someone enters the field of contemporary art, rather than any other field or genre (e.g., applied art, decorative—“beautiful”—art, or official, state-sponsored art), then it means that the artist has also chosen a very specific role for themselves and that role is a socially responsible one. A lot of artists I interview also talk about “critical art” and “meaningful art,” by which they mean that their art product needs to raise certain social needs, social problems, debates, and discussions. There is also a place for a very private, personal exploration that can be interpreted by various audiences differently, but the power of interpretation is not something that concerns a lot of artists. I have talked to people who said that they did not really care how their art was perceived. Often, they had very different ideas of what they had tried to create and why than the audience picked up through applied and participatory exploration, and the artists were very happy that the end product was something completely unanticipated. Since the production of art is quite a liberating space of expression, artists are not afraid to explore themes that they feel are important to them and to their community.

What are artists’ relations with the state like, especially in rich countries like Kazakhstan or Azerbaijan? Are they involved in state-sponsored celebrations of their sovereignty, identities, etc. (such as Expo Astana and other projects)?

This is a very good question. I have been working with the “state” concept ever since entering grad school (a long, long time ago) but I have never struggled with anything so much as I have with defining and analyzing how independent art and non-state-sponsored artists understand, visualize, and respond to the “state.”

In my forthcoming book, this is the major puzzle: to define and understand how non-state actors “see” and oppose the state. In many cases, the state also wants to appropriate artists and their symbolic capital. This tendency is seen not only in such countries as Azerbaijan or Kazakhstan, but also (increasingly) in Uzbekistan.

And by “appropriation” I do not mean that the state or state bureaucracy intends to directly ask a famous contemporary artist to prepare a project entitled “25 years of independence” or something of that ilk—though I think it could actually have been a very cool experiment if the artist was given complete freedom to conceptualize it.

This relationship is not always straightforward. A lot of contemporary artists are invited to participate in large “official” exhibitions, they are invited to state museums, and there is nothing wrong with that. On the contrary, it is a good starting-point for dialogue, as long as there is a balance in power relations and no strict censorship. There are thousands of shades of that censorship, including an artist’s own fears and self-censorship, and it has a very negative influence on the end product.

What do artists need to become more visible: money, exhibitions, labs, networks?

I recently came back from a field trip to Uzbekistan where I met with some old friends whom I interviewed six or seven years ago, as well as with new respondents: talented photographers, young musicians and artists, directors, amazing people. This whole experience was a self-reflexive trip for me, too, as an emerging writer from the region, a region I myself have to rediscover. But most importantly, during this roadtrip from Kunya Urgench in Turkmenistan to Nukus, Khiva, Urgench, Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara (the true Silk Road), I only solidified my thoughts about how these networks and groups of people co-exist.

There are many independent exhibit halls, places, and galleries. For me personally, it is always a pleasure to enter a contemporary art museum and stay there for days to think, write, study, and analyze. For example, I really loved how the Savitsky Museum in Nukus was renovated and how they moved a large part of the collection to the new building with better lights and more space. But that’s my personal view. Some artists prefer other spaces and tools of exposure that are less structured, less dominated, and more open. Technically, art is everywhere and we are reminded about it all the time: when someone next to us snaps a photo, when an artist sees something extraordinary in everyday life that we might not see. And for the exposure? Yes, it would be nice to have more catalogs, meetings, events, funding for these events where not only are artworks displayed but the audience also has a chance to hear what the artist has to say and can communicate with them. Central Asian artists have a lot to say and I really hope there will be more opportunities to hear them out.