“I started painting as a child. At first I copied some pictures and understood that this was what I liked—just to paint. Then I went to the children’s artistic school and then I was admitted to university for a degree in art. After university, I continued to develop as an artist and produced even more works. At the university, they taught us to paint academically; there were a lot of rules and restrictions. We were not allowed to paint naked people,”

Interview and text by Dr. Diana T. Kudaibergenova

Diana T. Kudaibergenova

Lund University/Cambridge University

Diana T. Kudaibergenova is a political and cultural sociologist working on social theory of power, nationalism, law, and elites in a comparative and historical perspective. Her first book, Rewriting the Nation in Modern Kazakh literature (Lexington, 2017) deals with the study of nationalism, modernisation and cultural development in modern Kazakhstan and her two forthcoming book projects focus on the rise of nationalising regimes in post-Soviet space after 1991 and contemporary art and power in Central Asia.

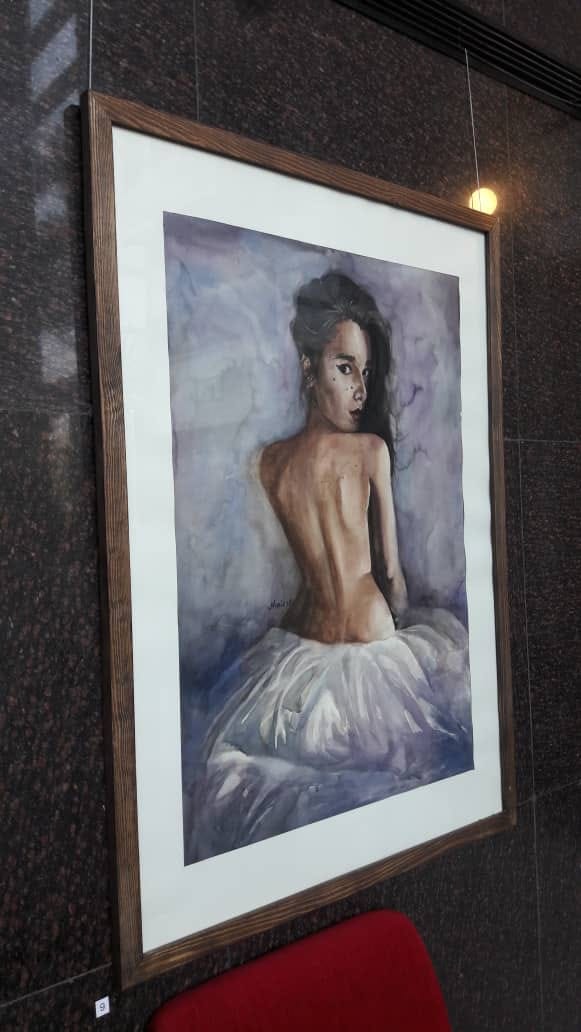

begins Marifat Davlatova, the artist whose recent art exhibition in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, spurred substantial debate in Tajik society. Davlatova herself was criticized for showing the naked bodies of women in public. Her art exposed divisions in the traditionalist society, in which she believes women are underestimated and confined to “appropriate” behaviour roles to which she objects.

The exhibition featured 24 works produced by Davlatova over the course of two years. Their styles ranged from pictorial art to realistic portraits to contemporary art. The focus of the exhibition was women and their daily lives in contemporary Tajik society. The exposition ran from August 21 to September 11 in the halls of the Sirene Hotel in Dushanbe, the city that is home to the 25-year-old artist.

“I wanted to show women as they go about their everyday lives, sometimes relaxing and sometimes changing their dresses to more comfortable, ‘house-worn’ clothes. I dedicated my work and this exhibition to the female body and to the protection of the female body from harassment,” says Davlatova.

All the works focus on re-interpreting the role of women in contemporary Tajik society, with the goal of making them more free and less fragile. They feature an array of women of all ages and backgrounds: ballerinas, young girls with flowers, and women who look the viewer in the eye. They are marked by recognizable attributes of Tajik national dress and accessories—hats, jewelry and colorful fabrics.

Are these the Liberated Women of the East?

“I wanted to add national attributes—tubeteikas (national hats), dresses in national silk pattern (ikat), pants, and jewelry. I am protesting with my art. Before, I used to paint landscapes, but later I realized the pressure from men for me to behave in a certain way and the patriarchal attitudes of the society, both men and women. I love freedom and it is very important for me to be able to choose a certain theme and express my ideas as an artist freely. Yes, these are the Women of the East (vostochnie zhenshini) and yes, they have rights: they need to be treated well and with respect. This is what I wanted to say with my work,” explains Davlatova. “And I will continue working on this theme no matter what.”

After her works became public, there was an outpouring of criticism on the internet, with comments calling for Tajik women to “dress up” instead of undressing, criticizing Davlatova for exposing naked female bodies, and arguing for the “authentic Tajik culture” that has virginal women as its ideal. Some even made religious arguments, citing the Quran.

In line with recent criticisms of feminist artists (including Kyrgyz singer Zere) directed at their body shapes, clothing, and visual positioning in the society as “female bodies,” she twists this paradigm by playing the same cards to empower those women who speak out and those women who aretargeted and labelled by re-traditionalization.

As Davlatova describes it,

“I myself experienced a number of inappropriate comments on the streets because I am a woman. Our men do not respect their wives, they do not respect women in general, they do not value what they have at home. With my paintings, I wanted to draw society’s attention to this big problem and to call out sexual harassment, catcalling, and disrespect against women in general. I wanted to say, look, our women are beautiful and valuable, they deserve their rightful place in the society.”

When I asked her about harassment, Davlatova sent me a Facebook post where a Central Asian woman raised concerns about the normalization of catcalling and sexual harassment. The text, which is typical of women’s experience, describes the horrors to which its author is subjected on a daily basis:

“Dear friends, I must admit [that] I have become used to sexual harassment. On the street:

1. They make noises, catcall, whistle, and make sexually charged jokes and inappropriate gestures;

2. When a group of men passes by, one of them pushes the closest guy to me, and he uses this opportunity to grab my breasts while falling on me;

3. A man who walks toward me catches me and grabs my hip;

4. Unexpectedly, a man behind me not only places his hand on my bottom but grabs it with his whole hand.”

The text goes on to describe how women feel in these situations—crushed, angry, agonized, but silenced because they fear further physical attacks: “I am afraid that my logical reaction of protesting [sexual harassment and grabbing] against this inappropriate behavior from male strangers may cause me to get a fist to the face or to be beaten up or kicked.” Unfortunately, women are not protected from such behavior, as it is hard to pin down the attackers or open a criminal case against offenders. This leads to women taking cautious but odd tactics:

“Every day when I walk on the street or when I am on public transportation or in any other [public] space, I turn on my internal ‘SNB’ mode. I constantly analyze people around me, as well as the surrounding space meters ahead of me. If I see a group of men approaching or just a suspicious man, I evaluate the degree of risk. I either go past on the other side of the street or turn away. And if it impossible [to do either of those things], then I hold my hands over my chest. First, to avoid getting grabbed. Second, to fight back.”[1]

Davlatova’s art was a response to precisely the harassment this woman describes, she explains:

“In light of such harassment and catcalling (despite the fact that it is now illegal in Tajikistan), I decided to address this issue by showing how women’s bodies are not ‘things’ or someone’s property and that women actually quite naturally use their own bodies in real life. I myself experienced catcalling before and I wanted to change people’s perceptions on this issue. I hoped that attitudes would really change in the two years that I worked on the exhibition.”

The project was not without challenges, however:

“What I wanted to show was how women live in a normal setting and that [their bodies and lifestyles] are natural and normal expressions of life. But it was very hard to find models for my works—many refused. But I still managed to find understanding people.”

Davlatova also shared her thoughts about her art education in Tajikistan, where students were not allowed to depict naked models and where uses and representations of “traditional Tajik culture” were censored. The paradigm of domination, where the structures of the pronounced power “culture” concept are not defined a priori but shifted and manipulated in order to change or restrict the content of alternative cultural production, is nothing new. However, this system has a negative effect on the formation of new ideas and new art. In the words of Davlatova herself, “art is avant-garde, it brings something new, very contemporary,” something that can change the way society thinks, perceives and lives. And if protest art is one of the venues for fighting the sexual harassment and discrimination against women that has been normalized through the paradigm of what is understood as “traditional or national culture” and “traditional values,” then it should have space for such expression:

“[I thought] we lived in a free republic, but everyone is afraid [of speaking out] and then I thought that it is not right. We live in the twenty-first century and I thought for a long time [before starting the work on the series of female bodies] and then I decided to work with the nude female body. Because I wanted to demonstrate the beauty of the female body and not to show it as if it were a thing or only seductive but as something much bigger, as a greater beauty—to show that female breasts, for example, are the source of children’s livelihood. But they [predominantly male critics]…think that the female body is all about shame. The female body is a lot more than that and I will continue advocating for it through my work,” concluded Davlatova.

Female Art in Central Asia in Retrospective

The representation of the female body—and especially the naked female body—has long been taboo. Yet throughout history, female artists have sought to reclaim the female body from patriarchal order, re-traditionalization, and the forces of “national culture.” Below are the names and works of some of the most noted female contemporary artists from Central Asia.

Umida Akhmedova, Tashkent.

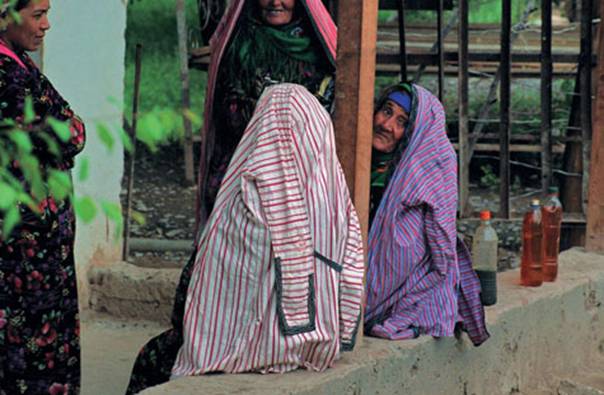

Umida Akhmedova is an acclaimed Uzbek director, photographer, and artist. She is the director of the film “Burden of Virginity” and has produced numerous artistic and photographic works. In 2016, she received the Vaclav Havel International Prize for Creative Dissent for her work and creative resistance. Akhmedova was the first professional female director in Uzbekistan. In the 2000s, she organized her own photo studio where she trained young photographers. Currently, she works on photo projects depicting the changing temporal perspectives of contemporary culture and everyday life. Photo from the series “Women and Men from Dawn to Dusk,” 2009-2010.

Almagul Menlibayeva, Almaty-Berlin.

Almagul Menlibayeva is a famous contemporary artist from Kazakhstan. She works in mixed genres and has pioneered her own exclusive approach to Central Asian video art. Women are a natural focus for Menlibayeva in many of her performances, videos, and still photos. Presented here is her highly acclaimed work Apa (Grandmother) and Apa №2.

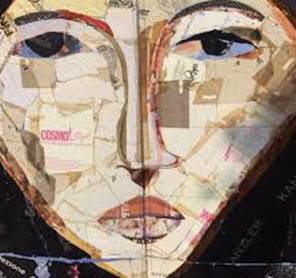

Saule Suleimenova, Almaty.

Suleimenova is one of the most popular local contemporary artists in Kazakhstan. She actively works on the deconstruction of national memory and archiving. In her recent works, she has also practiced “plastic art,” literally recycling plastic bags. Their layers on semi-installations and paintings represent the layered meanings and rewritings of local history. In her searches for the “authentic past,” Suleimenova uses the faces of nineteenth-century local women like those pictured in both of these paintings.

Suinbike Suleimenova, Almaty.

Suinbike Suleimenova, the daughter of Saule Suleimenova is a thriving young contemporary artist, director, and gender activist. She actively works with mixed media, through which she gives a voice to women. Pictured is a fragment from her film “0 Gender.” Suleimenova actively engages in rethinking power struggles and domination structures in everyday life.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Berlin.

Mukazhanova is one of the most talented Central Asian artists abroad. In her work, she explores the temporal disjuncture and embodied experiences of dis-identification and disorientation. She often uses female bodies to play with power discourses. Photos from her series “Mankurt,” which she has since expanded into excellent installations.

Aza Shadenova, London.

Aza Shadenova works with mixed media, brilliantly navigating borderlands in physical and cultural geography. Born and raised in several countries, she infuses a transcendent cultural perspective into her art, which offers a fresh, brave, and very powerful outlook with bright colors, a strong theme of liberty, and vivid representation. Aza also does excellent video art (for example, the “Disappearing City”), freely depicting the re-traditionalization of Central Asia. Shadenova is a multiplex fantastic artist-virtuoso. Pictured here is the work “Girls of Kyrgyzstan” (above) and her most recent work from the “Post-Nomadic Minds” exhibition that just opened in London.

Anisa Sabiri, Dushanbe.

Anisa Sabiri is a photographer, filmmaker, and poet from Dushanbe, where she is actively forming an artistic sphere by running workshops and organizing conferences and trainings for young artists. She is inspired by the representation of local culture and her constant journey to discover contemporaneity in local spaces and faces. Pictured: one of Sabiri’s portraits.

Ada Yu, Paris.

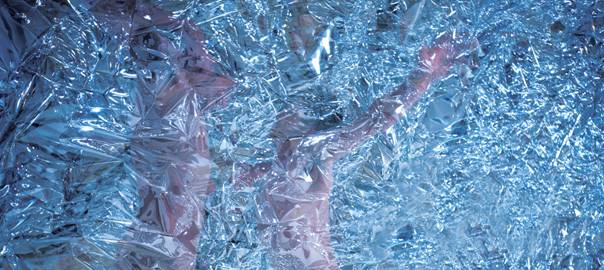

Exceptionally talented artist Ada Yu once made the body the direct focus of her artistic experiences and works. She successfully explored the limits and possibilities of body-freedom and body-expressions. Pictured: Ada Yu’s performance “Second Skin” at the Venetian Biennale in 2015 and a partial work from the “Delirium” series.

Oxana Shatalova, Rudny.

An artist, activist, writer, art curator, and public thinker, it seems as though Oxana Shatalova has explored all outlets for creative expression. Yet Shatalova continues to experiment with gendered themes. She is famous for her excellent video art, mixed media, photos, and performances. She was also in charge of the Bishkek-based STAB School of Theory and Activism and co-authored (with Georgy Mamedov) a number of texts on urbanism, memory, architecture, and what they termed “queer communism.” Together, they also co-curated the Central Asian pavilion at the Venetian Biennale in 2011. Most recently, Shatalova began writing sci-fi books. Pictured: Shatalova’s work “Woman-Loop.”

Zoya Falkova, Almaty.

Zoya Falkova can be called a feminist artist, as her works clearly focus on gendered order and roles in the family and in public. Her recent exhibition in Almaty featured paintings drawn with borsch and depicted the male body and genitalia (which were later covered after complaints). Falkova is not new to explorations of body politics, domination, and domestic violence in her very present and sharp art. Pictured: Falkova’s work “Evermust.”

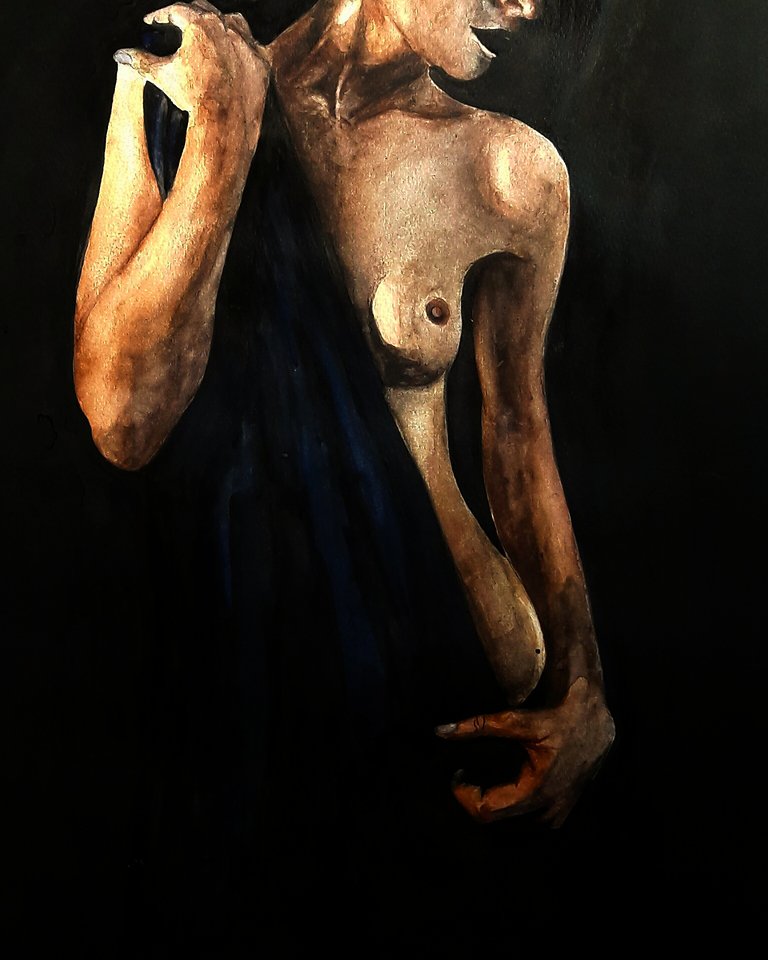

Marifat Davlatova, Dushanbe.

Marifat Davlatova’s work occupies a very strategic middle ground: she very skilfully uses fine art painting techniques but experiments with themes that are not particularly “classics” of the local official art tradition. Her works are quite clearly seen as a revolt played out as “official in form but oppositional in content.” The public criticisms that have made her art “notorious” to many actually lay bare the very purpose of this protest art—to speak to the traditionalist audiences in their medium, but to flip the script by allowing the new narrative to overpower traditionalist views of female bodies. Davlatova’s oeuvre is a striking example of shifting these power structures in a very unexpected medium.

There are currently two exhibitions, one in London and one in Berlin, in which female artists from Central Asia are participating. The Postnomadic Minds exhibition is curated by Aliya de Tiesenhausen and Indira Dyussenbina and is currently open in London (runs until October 16) at the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, London, E1W 3SG. On September 27, the exhibition featured a discussion of feminist art inKazakhstan and Central Asia.

On September 25, the Bread and Roses exhibition of four generations of Kazakh female artists opened in Berlin with a performance by SauleSuleimenova. The exhibition is curated by Dr. Rachel Rits-Volloch, Founding Director of MOMENTUM; David Elliott, Vice-Director and Senior Curator of the Redtory Museum of Contemporary Art, Guangzhou; and artist Almagul Menlibayeva. On September 30, the organizers will run a symposium on contemporary art, identity, shame (uyat), and the female body in the region

[1] From Burul Ai Note on 17 August 2018, via Facebook.