Austen Dowell is a Research Associate with the ERA Institute, focusing on analyzing regional affairs as part of the Central Asia Watch project. He has studied in Central Asia as a Boren Scholar, while also living and working in Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan. Austen currently serves as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ukraine.

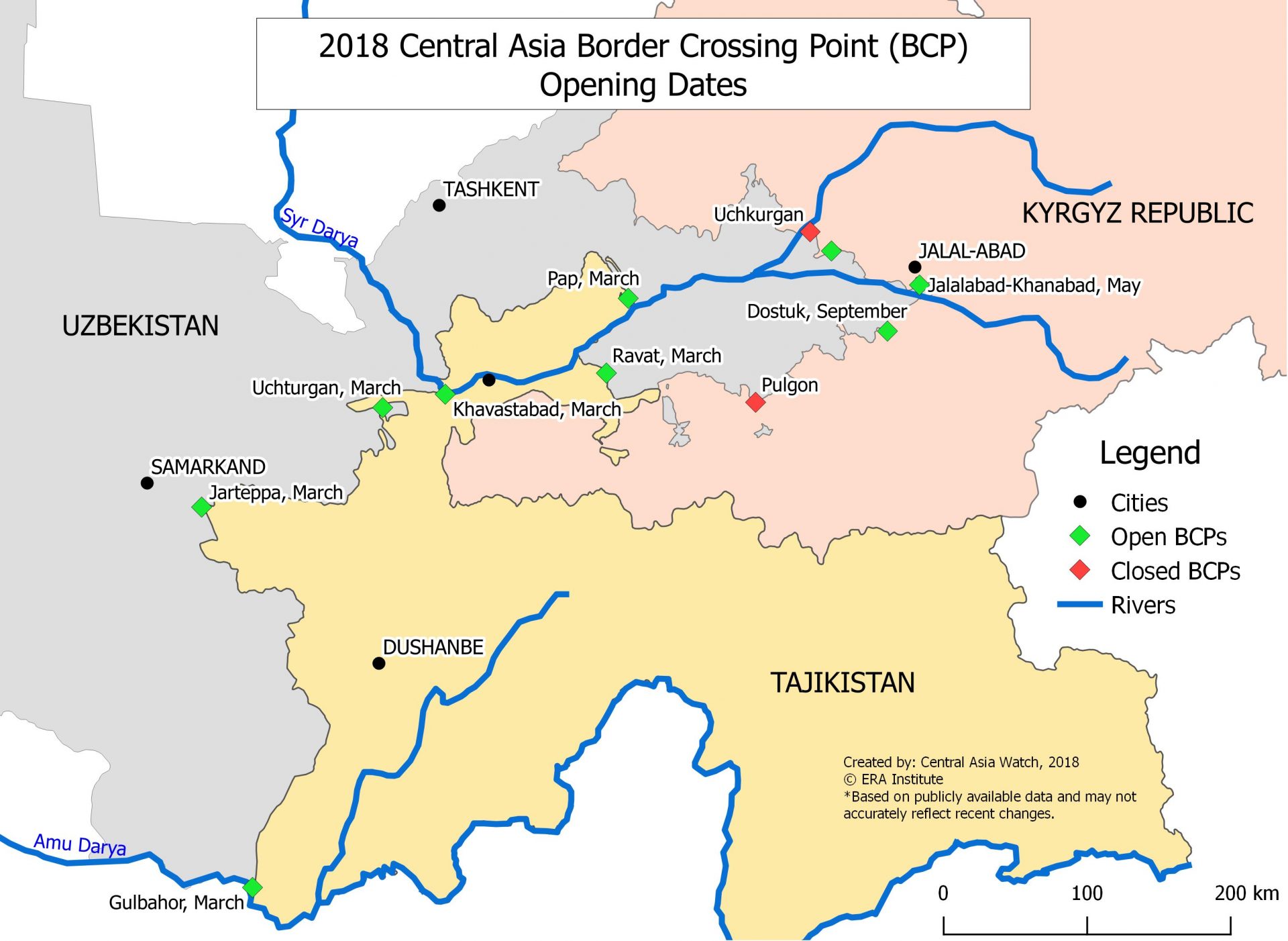

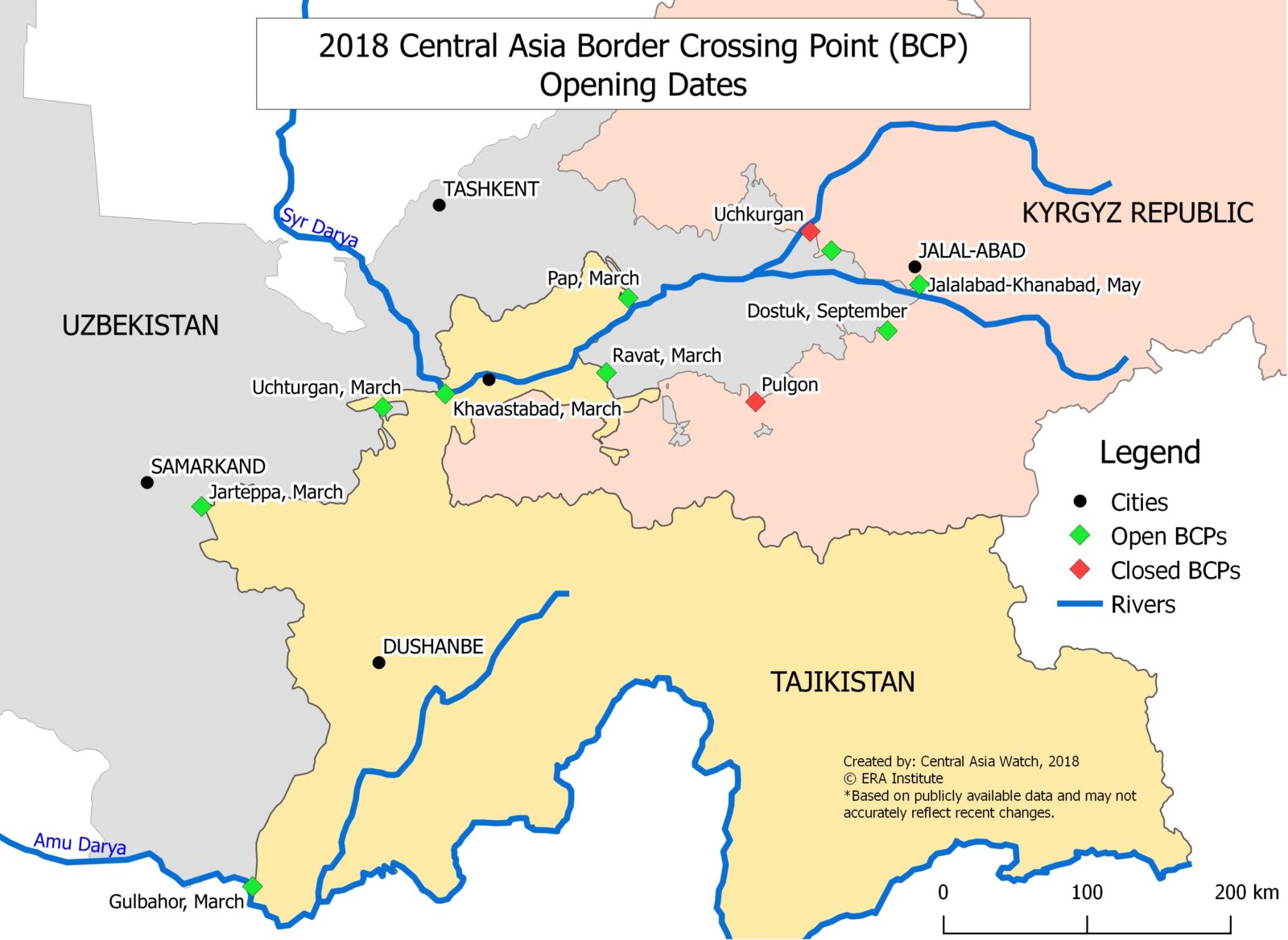

As part of the Central Asia Watch project, Austin Dowell has been looking at border cooperation through the lens of increasing travel between the countries of Central Asia, identifying 26 routes that have been created, resurrected, or proposed between January 2017 and December 2018.

In your article, you mention how the transport map of Central Asia is changing, with 26 new routes emerging in the past 2 years. Can you briefly summarize your key findings?

Twenty-six routes in 2 years is an interesting development in a region that many have viewed as locked in intractable border disputes. I looked at air, rail, and bus connections between the five countries of Central Asia, with a view to figuring out what was driving these additions. The majority of routes involve Uzbekistan, giving form to President Mirziyoyev’s articulated commitment to rapprochement with neighbors as well as his interest in galvanizing economic growth. Interestingly, these routes not only link the capitals, but also create an interesting spiderweb that seems to cover economically lukewarm but symbolically important routes (the Tashkent-Dushanbe air route had to be delayed in order to find passengers), cross-border connections (Ferghana Valley bus routes), long-distance alternatives (rail, bus, airlines connecting important tourist destinations), and more.

Why are these important?

It too often happens that foreign observers approach Central Asia solely through a Great Game-esque view of the five nations as static and troublesome obstacles that exist to be bypassed or intimidated in order to recreate some kind of mythical Silk Road overland route between the powerful countries of the West and East. This data helps propel a different narrative—one in which these countries possess their own voice and initiative, and their unique economic, geostrategic, and cultural visions create something that articulates their national identities while also providing a glimpse of an exciting future of regional collaboration and integration.

The data do not prove anything about the durability of these resurrected or newly-created connections, but we are able to get a sense of some tangible results of President Mirziyoyev’s much-heralded regional outreach. In terms of distinguishing between words and actions, that is a useful benchmark. This information also backs up other identified trends in the area: attempts to draw and facilitate international tourism, conciliatory gestures toward neighboring states, and an interest in enhancing cross-border infrastructure. Additionally, one gets a better sense of the multilateral nature of these trends: while Uzbekistan is at the center of many of these routes, it is far from the only country reaching out to others.

How does the construction of new roads relate to over-securitization and the terrorism threat? Are there any examples of such planning, like rerouting in Tajikistan to avoid Uzbekistan?

Well, it is such an interesting transition, precisely because transportation has been one of these five countries’ most commonly-utilized methods for addressing real and perceived threats over the years. In the aftermath of the 1999 Tashkent bombings, then-President Karimov was adamant about the danger of criminals and terrorists crossing the weak border areas in droves, which was right around the time Uzbekistan suddenly cut off most of their bus and train lines to their neighbors. Decision-making was obviously quite opaque, so the decision to limit travel and goods to Uzbekistan may in fact have been more geared toward economic outcomes, but it was certainly articulated as a security choice.

The 2011 incident on the Galaba-Amuzang railway was an even clearer convergence of transport and terror threats, with Uzbek authorities closing the crucial line to Tajikistan after a mysterious bombing blamed on terrorists. However, theories abounded about the strange response, with Uzbekistan using the situation to effectively block goods (including crucial supplies for building controversial hydroelectric dams) from entering southern Tajikistan for the next 6 years. It is no surprise that this line was announced to have been “repaired” in March 2018, just in time for the thaw in relations between the two countries.

Why might not everything be so rosy in the new Central Asia when it comes to border issues? Can you mention some of the issues that may require cautious optimism?

Nick Megoran has a great quote about borders, something along the lines of, “Ultimately, there are no intrinsically good or bad boundaries, only good or bad relations between states.” Rather than being these immutable lines in the land, borders can function as just another tool in the foreign policy toolkit. So as long as the five nations see value in opening borders and travel opportunities, yeah, things will improve. That being said, the 2017 Kazakh-Kyrgyz border-crossing debacle was a perfect example of how quickly things can change. After Kyrgyz President Atambaev accused Kazakhstan of meddling in the Kyrgyz elections by supporting an opponent to his preferred successor, Sooronbai Jeenbekov, the Kazakh authorities (which denied this) proceeded to crank up the difficulty of getting through the border. The resulting queues were pretty devastating for a space that had generally been regarded as fairly efficient up until that point, and the whole thing got bogged down in additional diplomatic complaints.

The liberal visa regimes currently being pursued are pretty game-changing and would seem to be a good step forward, but they will only exist for as long as their leaders deem them useful. The list of flashpoints and potential grievances is still pretty long, despite the positive talk among all parties. It is unlikely that the traditional divide between dry lowland growers like Uzbekistan and high-altitude water providers like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan will disappear overnight, so any failure in water-sharing negotiations could pk-callout to an instant snapback in border liberalization. Each nation has its fair share of grievances that have not simply disappeared in the last two years, so it remains to be seen how trusting each side will be moving forward.

The building of new routes obviously facilitates local tourism and trade, but the governments may hope that these routes will attract international tourists. How “hot” is Central Asia on the world tourism radar now? Are there any roads built to showcase the scenery?

Central Asia has always had an allure for the adventurer, but Uzbekistan’s rhetoric and increased infrastructure have really catapulted the area into the limelight. Uzbekistan even made it to 34 on the New York Times’ “52 Places to Visit in 2019” list, which would have been unthinkable a couple of years ago. Uzbekistan has been trying to leverage its position and resources to become a regional travel hub, and the border liberalizations are certainly helping with this. The elusive “Silk Road” visa is still in the works, but it has never been easier to get around the five countries in the same trip.

The overall effect of China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative is still up for debate, but the Central Asian countries are eager to attract large numbers of Chinese tourists. A much-heralded highway came online in 2018, linking China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. This will bring commerce and jobs, but it may also serve as a corridor for land-based tourism. That being said, tension between Han Chinese and Uyghur communities may act as a deterrent to Chinese tourists flocking to their next-door neighbors to the west. Additionally, the 2018 killing of four cyclists in Tajikistan by an Islamic State group was a major blow to claims that Central Asia is now a premier destination for tourists.

Nobody objects to a prosperous Central Asia, including a free movement zone for goods and people, yet we often hear it is still too “early” for any regional integration. Some say it cannot happen without major external financing or without an idea. What is your take on this?

I suppose it becomes a question of what “early” means. It has become more difficult of late to see regional integration as some sort of final stage in the evolution of a state, given the European Union’s raft of ailments. It seems vaguely paternalistic for Western analysts to chastise Central Asian leaders for failing to create united economic spaces while countries like the United States are still trying to re-imagine NAFTA and sparking trade wars. I do not believe that external financing is some kind of miracle cure either—One Belt One Road was supposed to be a game-changer, and yet there are increasing doubts about its economic or even geopolitical longevity. With any question of development, external financing is an incredibly complex issue that can either help or further damage a situation.

At the end of the day, I think it still comes down to questions of economic necessity and a creative approach to sovereignty. It seems that most observers believe that Uzbekistan’s pivot to regional engagement is primarily an economically-grounded decision meant to kick-start an often disastrously-run economy. That does not invalidate these halting steps toward regional integration; it just means that they are tied to demands for better performance. If a single travel space continues to be the best path for achieving this, then I think leaders will pursue it. This brings us to the elephant in the room: political will and creative approaches to sovereignty. I think the idea of a “Silk Road” visa is fascinating, because it hints at this long-standing idea that the five countries are bound by something greater than geographical proximity. Prosperity takes many forms, but I do not see why an economically-integrated coalition of nations with certain shared values and historical experiences should be out of the question.

Might the “road bubble” burst? It relies heavily on BRI and the supposed Silk Road, but it remains significantly cheaper to transport goods by sea. Can the overland road become cheaper than it is currently?

Remorseless logistics point to the superiority of maritime transportation for goods, and this is unlikely to change in the near future. Even heavily subsidized rail travel through Central Asia would have to deal with the issue of broad-gauge railway tracks, resulting in delays at the border. It is important to remember that Central Asia falls under the “Belt” rather than the “Road” clause of the initiative, with a different subset of objectives. Rather than a Hail Mary, speedy trip from China to Europe, we are looking at a progressive chain of linked countries that have increased connectivity to China. This means that more markets are created and raw materials are able to move much more easily.

The creation of routes between the nations of Central Asia is progressing, but any major projects are hampered by a lack of funding. Smaller-scale routes like the ones I have been looking at often built on older systems or were low-cost, but anything larger would most likely call for foreign investment. China has been incredibly open to dispersing loans and has forgiven them in the past, but it is not going to go and repave Central Asia on its own. That being said, the One Belt One Road project is a long-term initiative meant to absorb immediate costs with a view to improving the Chinese position in Eurasia. I think the only way we would see a dramatic “bust” situation is if China feels threatened enough (note the interesting developments in how countries like Kazakhstan have been handling the oppression of Muslim minorities in Chinese Xinjiang) by developments to start throwing around its weight and calling in the massive loans it has made. Otherwise, I suspect we will see on-and-off creation of highways and support for Central Asia-led transportation integration.