The name of the official news site of the government of Turkmenistan expresses what might be the closest thing to the sealed-off state’s official ideology: Zolotoi Vek, or Golden Age.

In recent years, Turkmens have been constantly reminded that theirs is a country enjoying unprecedented material and spiritual wealth. The latter is, according to the official narrative, helped along mightily by President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, the prolific writer of over 40 books, who has, since taking office, regularly made international news by appearing on stage with his grandson to slightly awkwardly perform Turkmen and international songs.

Author

Toni Michel

Toni Michel is a Eurasian affairs analyst based at the National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy. He holds an M.A. from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) and is the founder of the start-up consultancy Lockbreakers.org. Follow him on Twitter @villageescape.

The ordinary Turkmen is feeling little of the Golden Age his leader keeps talking about, however. With natural gas prices plummeting and only limited revenue reaching state coffers from gas sales to China due to infrastructure debts last year, foreign exchange inflows into the country have declined, leaving the Turkmen manat vulnerable. The artificially inflated fixed exchange rate of 3.5 manats to the dollar, in conjunction with heavily restricted capital freedom, are key factors in the impoverishment that is facing households all over the country, as many products are being imported and hence their cost has increased. Shortages of basic foodstuffs like flour, eggs, and meat are leading to long queues in front of markets and regular scuffles over food, even in the capital, Ashgabat. Unemployment numbers are hard to come by but serious estimates indicate figures of up to 60 percent. The state budget for next year has been reduced by 12 billion manat—in dollar equivalent, state budget revenues in 2019 should reach $29.96 billion if using the official exchange rate (3.5 manat per dollar) or $4.66 billion using the black market rate (18 manat per dollar). Meanwhile, the state is becoming ever more intrusive, cracking down on private alcohol sales and, crucially, foreign currency black markets. Meanwhile, citizens find it increasingly hard to leave the country and the state is keeping tabs on workers and students already abroad.

Turkmenistan’s outlook for 2019 is therefore highly uncertain. Yet three broad trends in the Turkmen state, society, and economy are going to influence life over the next 12 months.

Toward a Potemkin State

The regime rests on two pillars. First, because regional elites and identities are particularly strong in Turkmenistan, Berdymukhamedov’s power is built around a deal between elites from his native Akhal and the eastern Lebap regions to hold down the strategically located region of Mary in the south-east. There is little of substance that binds these strong local leaders to the government apart from the revenue flows that Ashgabat is distributing to key regional clans and powerful families to support their extensive patronage networks. After Russia announced that it would cease buying Turkmen gas in 2016 following a payment dispute and the global plunge in energy prices around the same time, this pillar of the Turkmen regime found itself under acute stress last year, resulting in erratic cadre reshuffles at the national level in order to prevent stable elite coalitions with institutionalized government resources from emerging. Of course, minister demotions also play well on TV, where the President is portrayed as a man of action who displays a hands-on attitude in the interest of his people and good governance.

Higher resource prices and Russia’s decision to resume purchases of Turkmen gas from January 2019 will somewhat alleviate the stress on Turkmenistan’s elite structure this year, as more revenues are again becoming available to distribute to key players in the country.

The second pillar of the regime is a different story. The broader population will continue to be bombarded with propaganda, while the state’s security services will likely be a much bigger presence in the life of the average Turkmen, particularly since open discontent and spontaneous small demonstrations in response to food shortages or abuses of power have been taking place intermittently since 2017.

To safeguard his regime against potential elite rumblings and popular frustration at the living conditions mentioned above, Berdymukhamedov appointed heavyweight security veteran Yaylym Berdiyev as Minister for National Security last summer. A former Defense Minister with a long history of service in the security organs, Berdiyev appears to have gained the President’s trust in the direct aftermath of Berdymukhamedov’s consolidation of power around 2008 and has served him in many roles.

Foreign Policy: Reconciling Isolationism with Reality

Turkmenistan has long been considered something akin to the Switzerland of Central Asia, not in its wealth, but in its foreign policy concept of neutrality: Ashgabat has mostly stayed out of regional political and economic organizations. However, in stark contrast to the small nation in the Alps, Turkmenistan has long been quite literally shut off from the outside world, allowing only a few tourists and a limited number of trusted foreign companies in and keeping economic and people-to-people exchanges with neighboring countries to an absolute minimum. This is set to change in 2019, for a number of reasons.

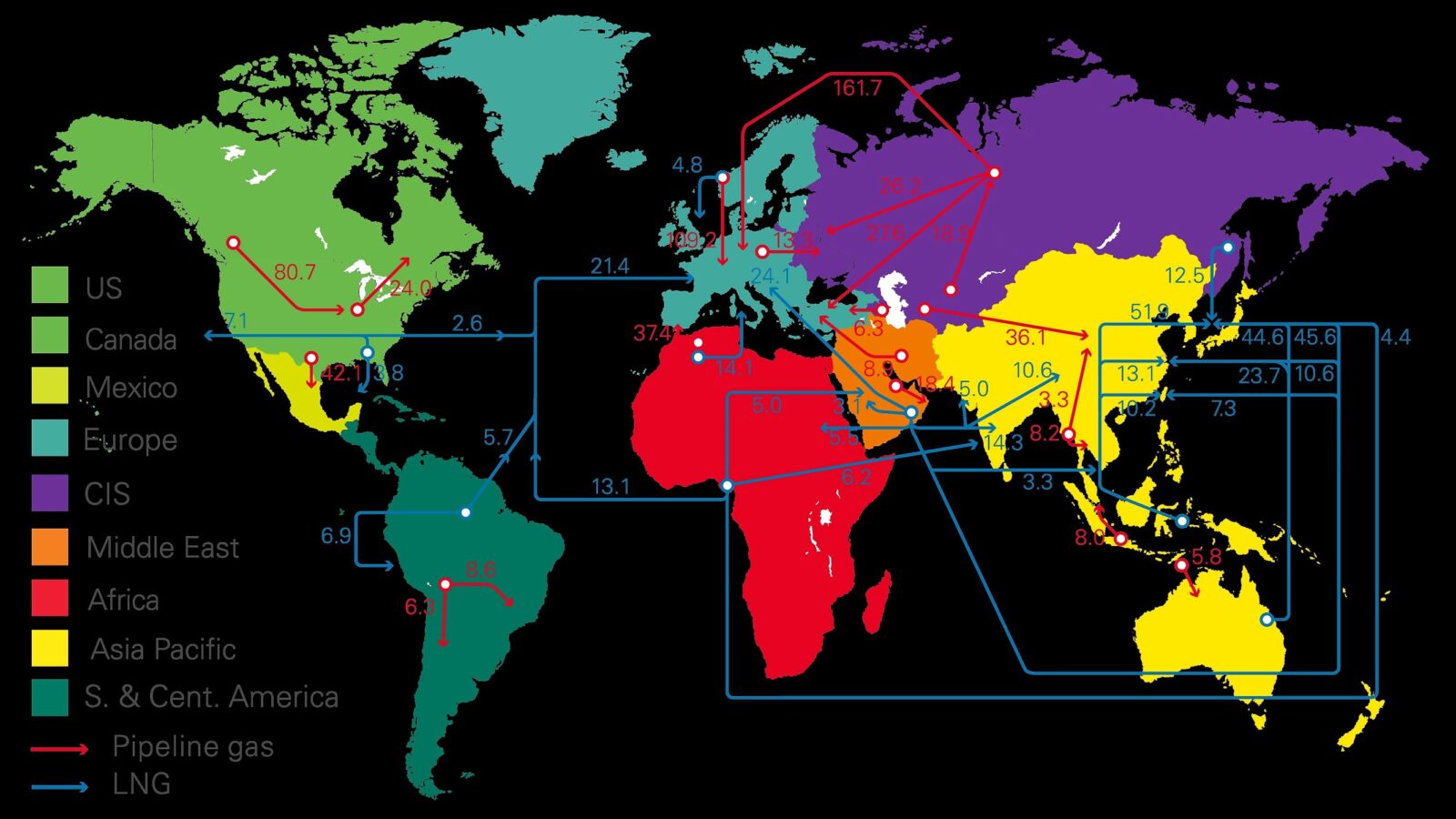

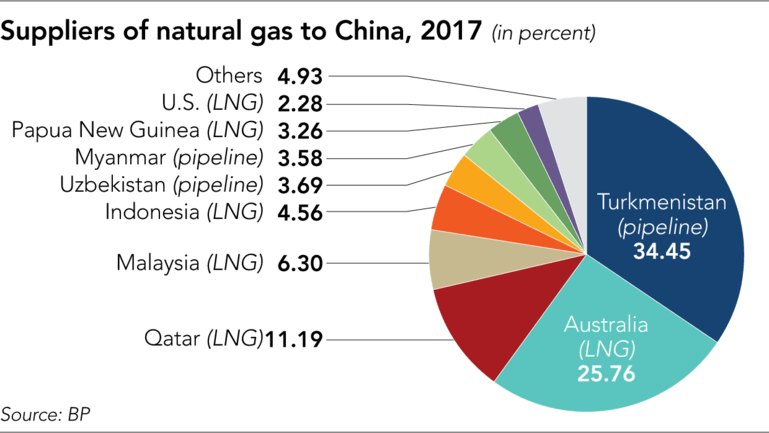

First, the government has apparently understood that export diversification is crucial if Ashgabat wants to avoid becoming a Chinese economic colony. Russia has most likely realized this as well, and it presumably played a large role in Moscow’s decision to resume gas purchases from Ashgabat this year. Turkmenistan is thus now also scrambling to take advantage of the accord reached in August 2018 on the legal status of the Caspian Sea and explore the possibility of a Trans-Caspian pipeline with Azerbaijan, with an eye to exporting Turkmen gas to Europe through the Southern Gas Corridor that runs through the Caucasus to Turkey. Second, Ashgabat will try to advance its own energy pet project, the $10 billion Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline (TAPI) that would make Ashgabat a key energy supplier to booming South-East Asian economies. Even ignoring the collapsing security situation in Afghanistan, this prestige project will run into increasing problems, as Iran is offering India and Pakistan a pipeline that cuts out both risky Afghanistan and the often erratic foreign policy moves of President Berdymukhamedov, who initiated an as yet unexplained economic campaign against neighboring Tajikistan last year while escalating simmering tensions with Iran.

This runs counter to the generally positive trend of intraregional Central Asian relations, which have been improving for some time and were boosted by the major opening-up of Uzbekistan following the death of former President Islam Karimov in September 2016. After skipping a major summit of Central Asian presidents that took place in Astana in March 2018 without any outside power, Berdymukhamedov might, ironically, fear finding himself alone in the isolationist policies; at least, Turkmenistan now seems ready to ride the new wave of Central Asian cooperation. Following several meetings with Uzbek leader Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Berdymukhamedov has taken some steps to liberalize trade at the rather sparsely populated mutual border and has gone even further with Kazakhstan by importing 100,000 tons of grain last year—an affront both to Ashgabat’s previous policy and to its fantastical official data on harvest yields, which belie the floods and storms last year.

Turkmenistan’s next-door neighbor Afghanistan will remain a major hotbed of instability, with its three-tiered conflict between the government, the Taliban, and infiltrating ISIS-affiliated groups. The limited peace talks with the Taliban will also put the internal cohesion of the group under significant strain, as strong regional commanders might well disagree with the wider group leadership’s approach and signal dissatisfaction through larger attacks. Turkmenistan will continue to lobby members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and particularly Russia, for material military support to secure the country’s long border with Afghanistan. Furthermore, Ashgabat will gain in China a new security partner in combatting radical groups in northern Afghanistan: China seeks to prevent separatist movements in its remote westernmost regions from profiting from this potential hideout.

All of this will require intense diplomatic efforts by Turkmenistan, whose diplomatic corps has been decisively weakened by the departure of a deputy foreign minister who has been tapped to become the head of Akhal Region—and is, incidentally, the President’s own son, Serdar Berdymukhamedov.

Light and Shadow in the Economy

International bodies often put Turkmen GDP growth somewhere between 5-7%. With access to the country and to reliable data heavily restricted, however, such numbers have a credibility problem. At the same time, the expensive new seaport at Turkmenbashi and Ashgabat Airport will continue to report substantive losses due to overcapacity, while unsound economic policies and declining foreign investment in Turkey will pk-callout to the devaluation of remittances from its large diaspora working there.

China’s slowly decelerating economy will likely not impact Turkmen gas export volumes in 2019 (these increased from 29.4 bcm two years ago to 31.7 bcm in 2018). The problem that these exports are not translating into significant budget revenues due to infrastructure debt will be offset by Russia’s aforementioned decision to resume gas imports from Turkmenistan. Russian state mineral and resource companies are also likely to enter the Turkmen market, pending a successful trial period in the energy sphere with timely payments from the Turkmen side.

In the non-energy sector, after a long period of stagnation there will be some new momentum, with several projects for fertilizer and chemical plants planned. In this context, the consolidation of Japan’s Toyo International Corporation in Turkmenistan’s highly unreliable business environment is quite a positive sign. And with the aforementioned imports of Kazakh grain, positive signals to German investors, and the EU’s new connectivity strategy for the region, it seems that Ashgabat really is, to an extent, moving away from its isolationist stance. Yet the volatile investment climate will likely pk-callout to new payment disputes and international arbitration lawsuits, as Minsk-based Belgorkhimprom, the company that built the under-performing potash fertilizer plant in eastern Turkmenistan, recently learned.

Questions Raised for 2019

All in all, it seems that Turkmenistan is changing on a number of fronts. Yet while the government is eager to charge ahead in some areas, it is frantically trying to push back against the new constellation elsewhere.

2019 will be a crucial year for Turkmenistan and the wider region. In it, we should learn the answers to a few crucial questions:

- How much is Russia willing to spend to keep Chinese influence out of Central Asia?

- How sure are regional elites that Berdymukhamedov is still the best person to protect their incomes?

- How long will the Turkmen people put up with the end of subsidies, food shortages, and humiliation?

- And will somebody tell the President that his energy is better spent focusing on reforms than on producing ever more music videos?